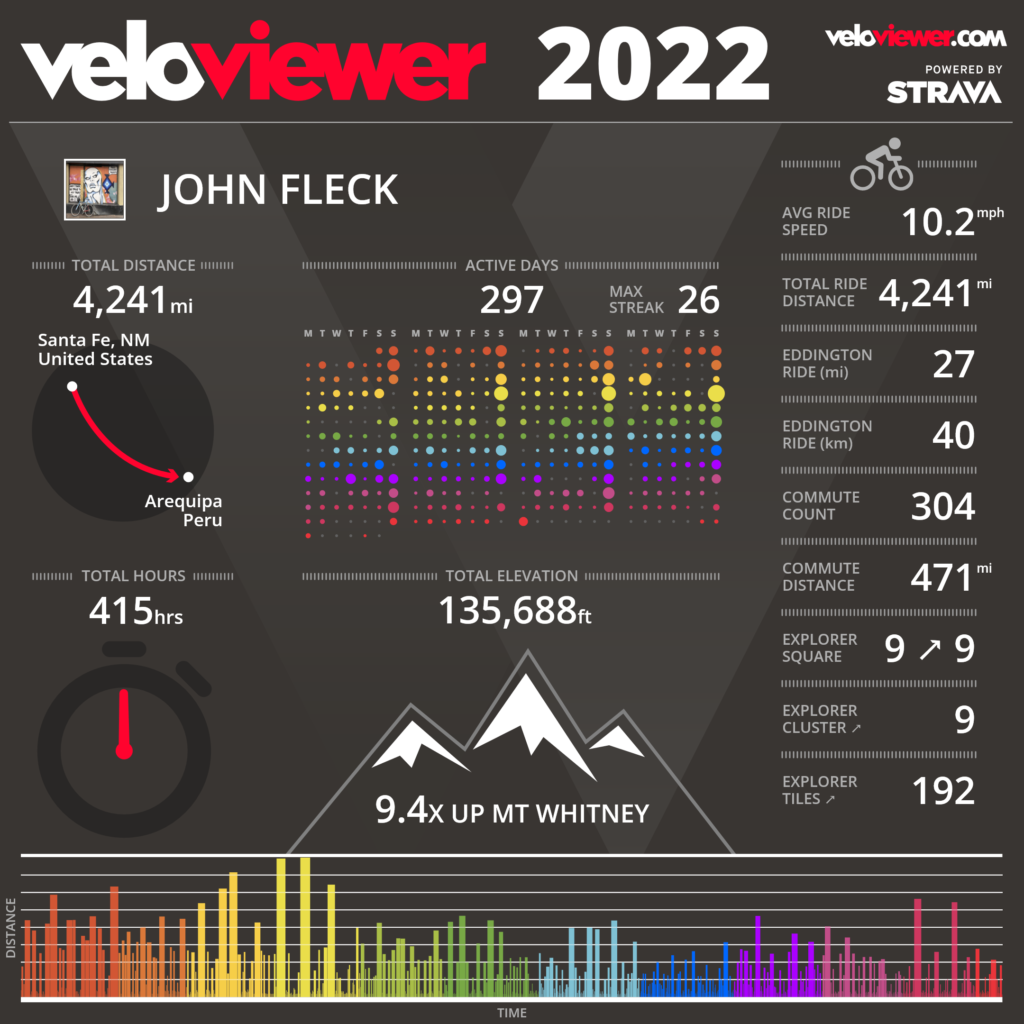

2022, the year of Squadrats

No bad days on the bike.

At the risk of a tortured metaphor, rides are the warp threads of the loom of my life, bound firm in the frame of the loom as I weave the day’s events around them – the places I go, the things that I do, and the rides that get me there and back.

I remember lunch with my friend Liz – and the bike ride I took to get there, winding through the industrial freeway zone, cranes and graffiti and homeless encampments, on the way to the restaurant.

I remember pre-dawn breakfasts at the Frontier with my friend John, clipping on the lights and bundling against the cold, locking up next to a homeless guy’s epic touring rig, always parked at the same spot, and he’s always sitting at the same spot, sipping coffee to warm up, able to look out the window to keep an eye on the bike.

I remember the conference in Salt Lake City and not one but two epic rides on the way there, in the San Juan Basin and along the Colorado River. The conference in Boulder and the loop with Eric around Dillon reservoir, the ride to the conference from the hotel in the morning and the long walk back to the hotel with my friend Bill, walking the bike through a delightful throng of Deadheads converging for the evening’s merriment, because Boulder, amiright?

I especially treasure Sunday rides with my friend Scot which, absent my crazy Colorado River conference schedule or Covid, anchor each week, foundational.

The joy of the ride to work, and the ride home (I exploited a cool new alley cut-through this year, just a few blocks from my house, how had I missed it all these years?).

Some days I lock the bike at the law school rack, but more often it’s propped up against the bookcase in my office. A happy object always.

Riding everywhere

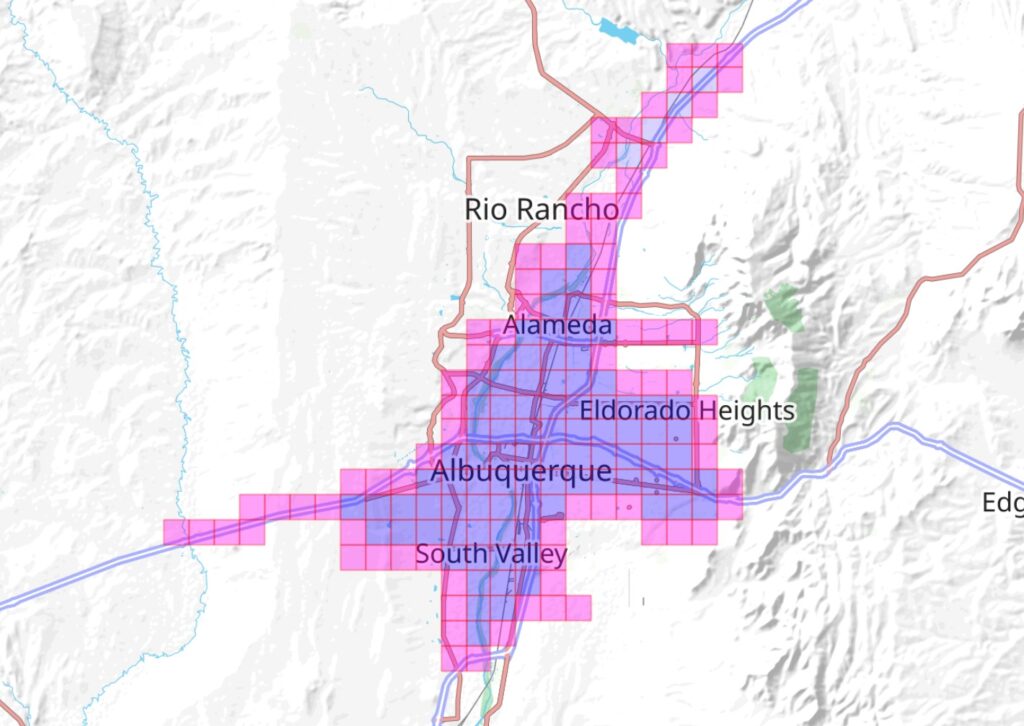

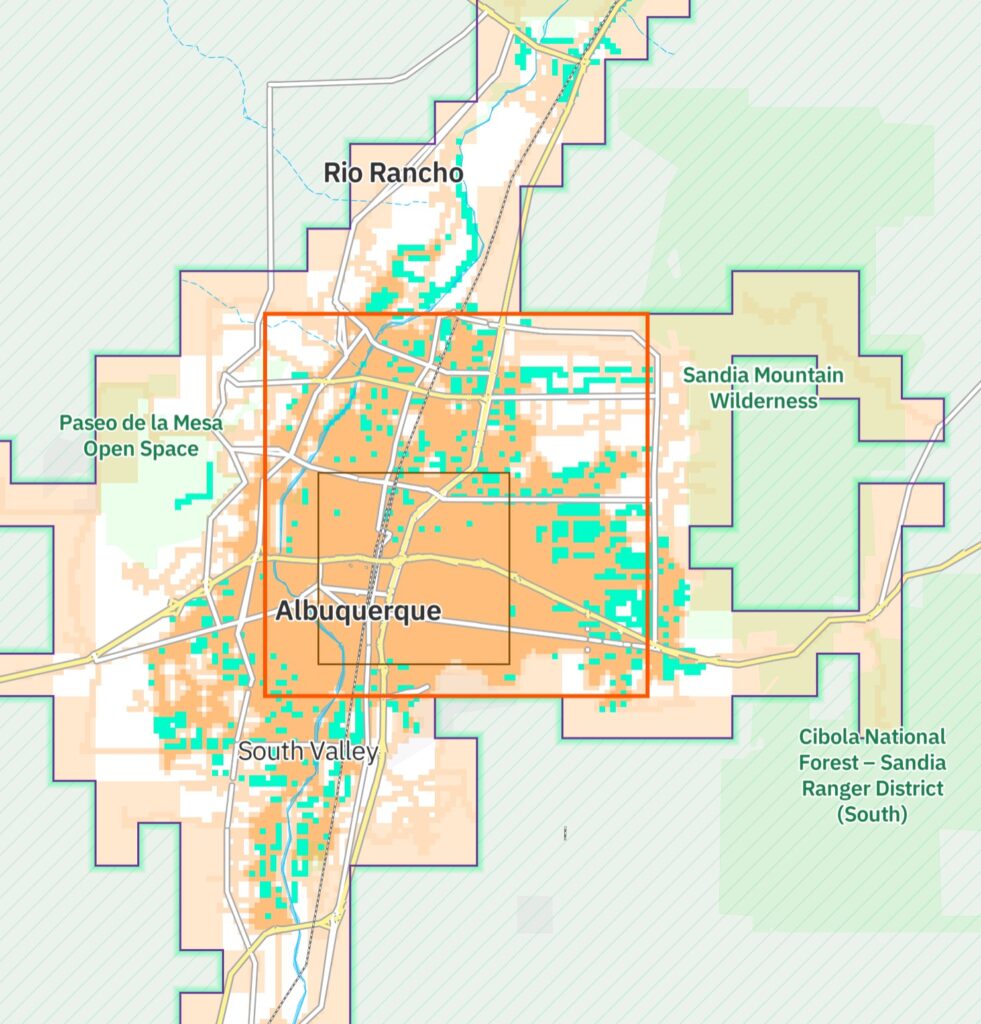

Tiling Albuquerque – a map of the places I rode in 2022 in Albuquerque

Some years ago I dug through all my old devices and hard drives and cloud services and assembled a relatively complete record of all my bike rides since 2008, what I call “the GPS era” – 5,176 rides, 39,365.1 miles.

All that data sits in Strava, and Strava makes it relatively easy for developers to build creative new products, which has lead to all sorts of mappy game innovations.

In 2020, I was already riding a lot when pandemic isolation turned the bike rides into a desperate, manic adventure. I’d discovered Veloviewer and “tiling” – using our bikes’ GPS records to keep track of where we’d ridden and, more importantly, where we hadn’t.

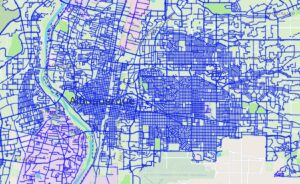

In blue, the Albuquerque streets I’ve ridden.

In 2021, I added Wandrer – keeping track of which streets I had and, more importantly, hadn’t ridden.

This year I added Squadrats, which is the most fun of all. Veloviewer’s squares are a bit less than a mile on a side. Ride (or walk or whatever) anywhere in a tile and you’ve got it. The big tiles are pretty easy to get. In Albuquerque, I quickly filled in the entire city.

So after a couple of years of working on it, the only new Albuquerque tiles left required some epic explorations to the west, some clever work to thread through to the south without trespassing on Pueblo lands, and increasingly lengthy adventures to the north.

I’m getting old for “lengthy adventures”, frankly.

And then I found Squadrats. It takes the Veloviewer-sized tiles and doubles (octuples?) down, dividing each tile into 64 mini-tiles. The result was a year of joyous riding going back to all the little tiny bits of Albuquerque I’d missed. Using the standard Open Street Map grid, it divides up squares that vary by latitude, but here in Albuquerque they’re about 800 feet on a side. Filling in a map at that density requires geographic intentionality, focus.

The rural-junkyard interfaced.

Thus a “wrong turn” down the cart path at Los Altos Golf Course (“I’m sorry, it looked like a bike path.”). A flood control tunnel in the far northeast. The junk yard hard against an irrigation ditch and alfalfa field in the South Valley. Places I’d never have gone in the pre-Squadrats era.

Even before tiling, our practice of riding in weird places has always encouraged strange encounters.

My favorite was the time the caretaker at the Albuquerque Dragway politely informed us one Sunday morning that we weren’t supposed to be there. “Chased out” is too strong a word for the encounter as he rode up on his ATV. It was a polite exchange, though it was hard to make the “wrong turn” argument given that we’d lifted our bikes over a locked gate to get in. He then escorted us out and, in answer to our question, pointed us to a good spot to hop another locked gate to trespass on his neighbor’s property.

Good guy.

This year’s best Squadrats tiling adventure involved being politely told we had to leave Albuquerque’s Balloon Fiesta Park (“So sorry,” we said, pointing helplessly at our mobile phones, “Google made it look like this was a road.” Works every time.), then circling around the far side and sneaking back in.

Tiling can feel a bit rascally. That’s a part of the fun.

Fleck’s Squadrats map. New mini-tiles for 2022 in green.