By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

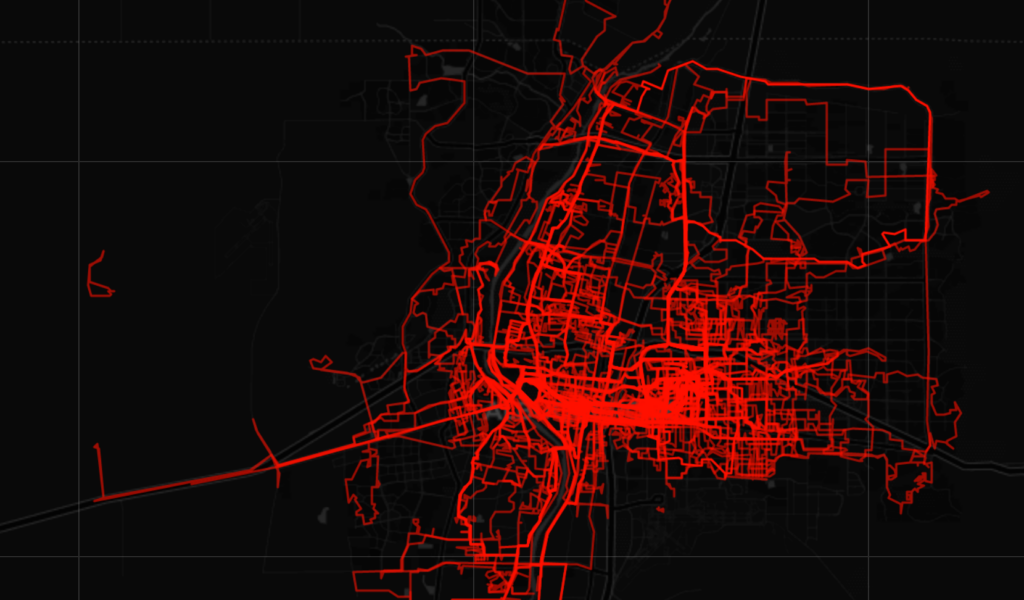

As the Colorado River Compact Commissioners gathered in Washington a century ago, a storm settled over the nation’s capital. Photo courtesy Smithsonian

Herbert Hoover’s words a century ago were chosen with care. Might it be possible, he wondered, for the state officials gathered around him that day “to agree upon a compact between the seven states of the Colorado Basin, providing for an equitable division of the water supply of the Colorado River”?

It was Thursday January 26th, 1922, at 10:00 AM, as the eight members of the Colorado River Commission met in Washington, D.C. gathered for the first time at the offices of the United States Department of Commerce. Over the next 11 months they would negotiate the details of the Colorado River Compact which they signed on November 24th, 1922.

“It is hoped that such an agreement,” Hoover added “… will prevent endless litigation which will inevitably arise in the conflict of states rights.”

Hoover, then the Secretary of Commerce, had been appointed by President Warren Harding to be the commissioner from the United States and lead the effort. In addition to Hoover, each state sent a commissioner appointed by its governor:

- Arizona, W. S. Norviel, State Water Commissioner

- California, W. F. McClure, State Engineer

- Colorado, Delph E. Carpenter, Special Water Counsel

- Nevada, Colonel James G. Scrugham, State Engineer

- New Mexico, Steven B. Davis, State Supreme Court Justice

- Utah, R. E. Caldwell, State Engineer

- Wyoming, Frank C. Emerson, State Engineer

Hoover’s opening statement was carefully prepared.

While there is possibly ample water in the river for all purposes if adequate storage is undertaken, there is not a sufficient supply of water to meet all claims unless there is some definite program of water conservation.

In the language of the day, “conservation” meant something very different than its modern usage. It meant, quite simply, building dams to “conserve” water that would otherwise be “wasted” to the sea. But the enormity of the dams contemplated left an equally enormous institutional task – developing the rules needed to allocate, and therefore share, the river’s waters.

The Federal Role

As to the federal role, Hoover mentioned four interests:

- control of navigation

- protection of US treaty obligations

- development of national irrigation projects

- power development on public lands

“The sole object of the Federal Government,” Hoover said, “is to secure development of the river in the interest of all.” After his opening statement, Hoover was formally elected Commission Chairman.

The Commissioners Speak

Each of the state commissioners gave an opening statement.

Hoover first turned to Colorado’s Carpenter, acknowledging his role in the creation of the commission. Agreeing with Hoover, Carpenter stated “the prime object of the creation of this Commission was to avoid future litigation among the states.” He added that “facts are always the basis of legal problems and hence the facts must be studied.” The need to avoid litigation and study the facts was a common theme to the statements of all seven state commissioners.

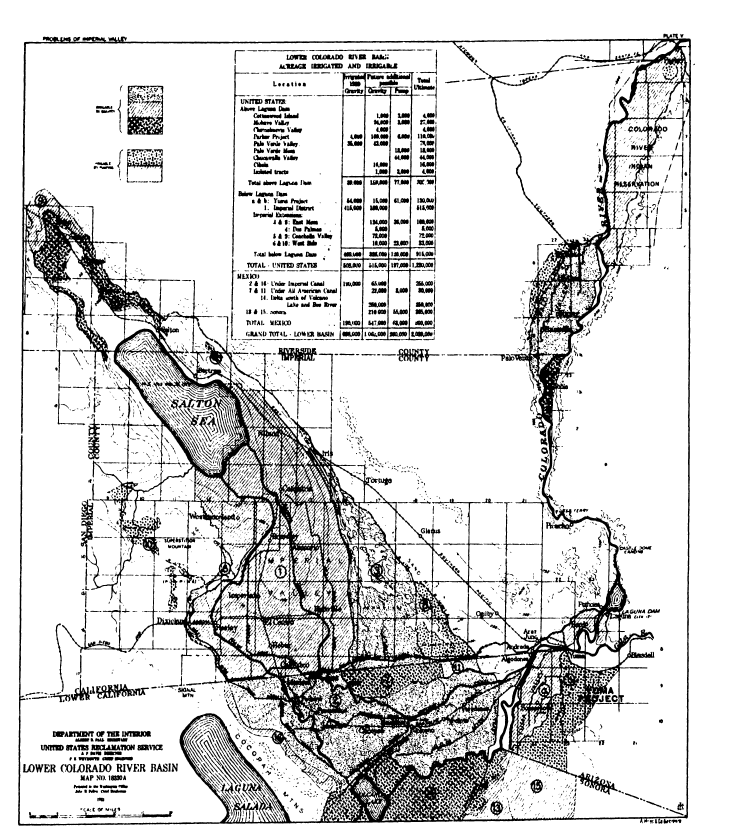

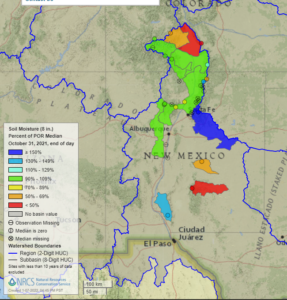

The commissioners then heard from Arthur Powell Davis Director the U.S. Reclamation Service and nephew of the legendary John Wesley Powell. Davis, who began studying the Colorado River Basin in 1895, impressed the commissioners with his knowledge of the Colorado River. He emphasized Hoover’s conclusion that with conservation the river had a sufficient supply of water to irrigate all lands that could be “favorably reached.” Davis suggested the Commission could successfully apportion the river’s waters among the seven states based on the number of irrigable acres in each state. Over the next six meetings, they would pursue this approach without success.

The Commission then heard from representatives of the Army Corps of Engineers, the Federal Power Commission, and finally the U.S. Geologic Survey. In a short statement, Nathan Grover, Chief of the Hydrologic Branch, told the Commission that the resources of his agency were at their disposal.

What he did not mention was that his agencies’ Colorado River experts, including E.C. LaRue, did not share Davis’ optimistic view that there was enough water for all. Instead, they would have urged the Commission to be much more cautious and conservative in allocating the river’s waters.

Before the meeting ended, the Commission appointed committees to look at the legal issues, determine the water supply available, and ascertain the demands for water. They also tabled a proposal by Arizona’s Norviel to create a permanent commission. By the end of the first meeting, it was clear that four individuals would dominate the Commission. Herbert Hoover, the confident and self-assured mining engineer, took command of the effort from the first meeting, but too often chose expedient results over a thorough understanding of the facts. Delph Carpenter, the brilliant legal strategist and father of interstate water compacts, fearing the power of centralized government and the societal changes being driven by new technology, fought for state sovereignty in an increasingly complex interconnected world. Winfield Norviel, the tenacious Arizona Water Commissioner, understood that unlike the six other states, the Colorado River system was the only source of surface water for Arizona’s future, but his negotiating style alienated the other commissioners. Finally, Arthur Powell Davis, the hands-on engineer who understood that a peace pact among the states would open the door to the development of a new generation of massive water projects his agency would build and operate. Like Hoover, he wanted to avoid the Commission getting bogged down on the facts. Now, with Grover’s acquiescence, he controlled the facts the Commission would use.

The first meeting ended on a positive note. Although the Commission would soon find out how challenging it would be to turn broad concepts into agreement details, the optimistic view of the water supply put forth by Davis, Carpenter’s legal discipline, and Hoover’s pragmatism would ultimately prevail.

As an omen of the future turmoil facing the river, that evening Washington D.C. was hit with a record snowstorm. A Nor’easter lashed the region, dumping over 30 inches of snow on the city, enough that the weight of the snow caved in the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre, killing nearly 100 people. The storm became known as the Knickerbocker storm.

The Commission held two short meetings on Friday January 27th, then got together again on Saturday January 28th to begin the real work of hammering out a compact.

Stay tuned.