It rained this afternoon at my house.

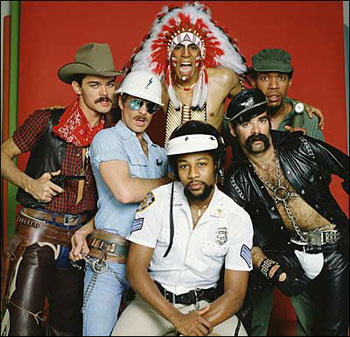

raindrops on my front walk, July 2, 2011

The physics of raindrops, I once learned, means that the largest raindrops falling out the bottom of a thunderhead hit first, and I was sitting in my office at the back of the house writing when I heard them banging onto the metal roof. I went out to the living room to make sure Lissa heard it, then walked out shirtless and barefoot and stood beneath it, flashing fingers to her in the front window as I counted off the raindrops hitting me. One. Two. ThreeFour. FiveSixSeven (two hands now).

I sat for a long time on the front porch watching and smelling – not enough for the cars going by to turn on their windshield wipers, but enough to wet the street so their tires sizzled.

I’ve been zigging and zagging this week, trying to get my head around things without precedent, either in personal experience or in the data we substitute when personal experience misleads, or is not enough.

To say it has been dry this year in New Mexico falls so short of the mark that I don’t know where to turn next. As a journalist I’m a bit of a technocrat, a collector of numbers and measurements. It’s usually a strength, but feels right now like a weakness. A week ago, I’d been planning a newspaper piece that tried to capture the Big Dry in numbers, using the completion of 2011’s first half-year as one of those calendrical milestones that give us an opportunity to take stock.

Then shit started burning, and the numbers used to measure this sort of thing veered off in weird directions – acres burned instead of acre feet of water, percentage forest fuel moisture instead of percentage precipitation. And lingering beneath it was this uncomfortable sense that, as a writer, I’ve got nuthin’ in the face of this truly remarkable phenomenon laid out before me.

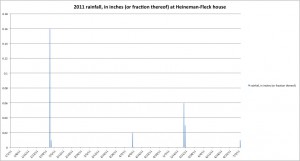

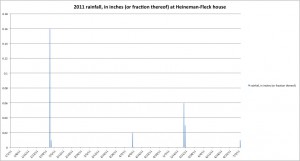

precip at my house so far in 2011

I’ve got a shit ton of numbers, everywhere I turn. For grins, for example, the daily precip at my house since Jan. 1: Six days total, just two of them above 0.04 inches (0.1 cm), today the first measurable since May 20. Click to biggen it, look at the y axis. A measure of our pain.

Working the fire story, I heard some remarkable stories from folks I’ve known for years, forest ecosystem types who work in the Jemez, who measure it but also live in it. And it’s the living in it, in this big dry, that’s so remarkable, and for which words so completely fail me.

I can imagine someone has done science about this, made up one of those “just so stories” that evolutionary types so love about how humans evolved with an exquisite sensitivity to rain because our lives so depend on it. I can understand how we’d be wired by our ancestry to get tense at times like this.

It is frankly one of those “It is impossible to say just what I mean” moments. Suffice to say it’s been really, really dry here, and the joy I felt at the 0.01 inch of rain I measured in the backyard gauge is both genuine but also sadly telling.