Lissa and I flew to St. Louis two weeks ago to visit a dying old man we love very much.

Bill’s been very sick. Lissa called in September to say we wanted to come see him, but he put us off. He didn’t want us to see him that way, to remember him that way. But then he changed his mind, called Lissa in what was either a moment of great weakness or great strength, or both, and asked us to come.

Family roots on Lissa’s side go back a ways in Missouri, and even though I’m distant from it, and we’re mostly disconnected from the place other than her Uncle Bill, I love having married into that. I’m from California, where place is mostly shallow. St. Louis feels deep.

Bill was staying with a friend in a brick row house in the old Irish neighborhood they call “Dogtown”. Climbing the flight of stairs to see him felt as though we were passing through a window in time. It was hot, and they had a window open with a fan blowing.

I don’t want to oversell the trip-back-in-time thing, because Bill was in many ways a modern man. He drove a Mini Cooper. But he was rooted in a different time. He had no use for cable, and listened to baseball on the radio.

He didn’t have the energy for much, but we grabbed the hours with him we could, mostly sitting on the couch in the upstairs row house living room.

Our trip put us in St. Louis Friday, Oct. 7, the night the Cards beat the Phillies in what was apparently an epic 1-0 game to advance to the National League Championship Series. I say apparently, because Lissa and I didn’t notice until we saw it in the paper the next morning. We were kinda distracted.

When we saw Bill that morning, he told us he’d listened to the game on the radio. He seemed to have enjoyed it, as much as he could enjoy anything.

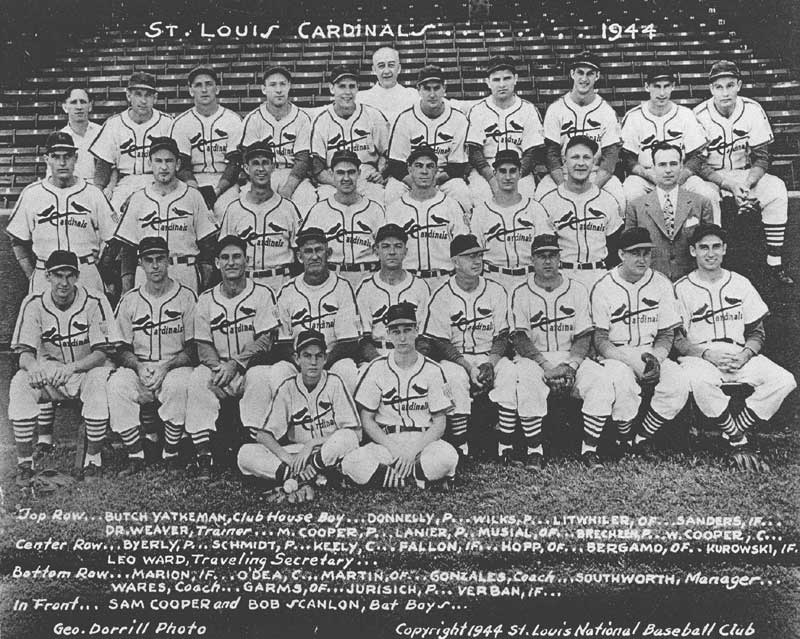

Baseball’s been all tarted up with cable TV pizzazz – graphics that show where the pitch went and super-slow-mo and “catcher cam”. But at its heart, from Bill’s time, it is a tale for radio, a game suited to simple story-telling. It’s not that Bill was a sports fan. It’s that, in his time, listening to the Cardinals on the radio on a fall evening when they had a chance to make the World Series was what you did.

Bill died Tuesday.

Go Cards.