I don’t see how this ends well.

Most of the major players – the ones that matter, anyway, by which I mean Arizona, California, and the federal government – appear boxed in by constraints they can’t seem to overcome, while the water in the Colorado River’s big reservoirs is circling the drains.

Arizona’s giving up a lot of water right now, and it’s hard to see how they solve their in-state politics and give up more without California coming up with substantial cuts of its own. Meanwhile California’s internal politics have so far constrained it from coming up with meaningful contributions. This may change soon, but the numbers being discussed may not be enough to move the needle as far as it needs to move. And the federal government seems torn between tough immediate actions and placing responsibility on the states to come up with a plan to save themselves.

Last week’s Water Education Foundation Colorado River symposium in Santa Fe was striking.

It’s an invitation-only event, and I’m not sure what the ground rules are, so I’ll treat it as a sort of “Chatham House Rules” thing.

I will say this. I moderated a panel. Harsh words were exchanged. I was kind of an asshole as I tried to get people to say the quiet parts out loud. But right now, we need to be saying the quiet parts out loud, because the water is circling the drains.

the status of the reservoirs

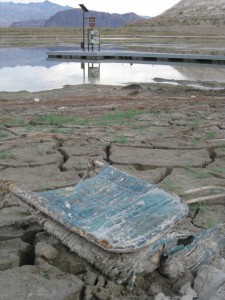

obligatory cracked mud photo (Mead is, like, 40 feet lower right now than when I took this)

Lake Mead will end water year 2022 next Friday with a surface elevation ~1,044 feet above sea level, down 1.8 million acre feet from a year ago.

Lake Powell will end the year at somewhere around elevation ~3,529, down 1.5 million acre feet from a year ago.

Flaming Gorge Reservoir, which must now be in the end-of-water-year mix because of the way Reclamation and the states have begun moving water around like pawns on the Upper Basin chess board, will end the year at elevation 6,013, down 300,000 acre feet from last year.

Absent action by water users to use less, next year’s not-all-that-farfetched possibilities (by which I mean the Bureau of Reclamation’s latest “minimum probable” forecast) has Powell dropping below minimum power by the end of 2023 – and staying there. Absent downstream action by water users to use less water, Mead drops to 1,016 by the of water year 2023.

If the federal government holds water back in Powell to prevent the need to use the dam’s bypass tubes, that drops Mead even farther.

For those not steeped in the numbers, this is cracked-mud, five-alarm fire bad.

2022 Water Use

| Use | Allocation | percent | |

| California | 4.445 | 4.4 | 101% |

| Arizona | 2.056 | 2.8 | 73% |

| Nevada | 0.236 | 0.3 | 79% |

| Mexico | 1.45 | 1.5 | 97% |

Source: USBR, Lower Colorado River Basin water use forecast, retrieved 9/25/2022

Californians are touchy about these numbers, specifically the observation that they’re taking more than their full allocation this year, even as the reservoirs are tanking. They point out that in recent years they have used significantly less than their allocated 4.4 million acre feet, banking unused water in Lake Mead as a hedge against drought. Which they’re suffering now, massively. Which is true, and fair to point out.

So, for completeness sake, here are the three Lower Basin states’ annual take on Lake Mead going back a decade.

| Arizona | California | Nevada | |

| 2013 | 2,778,867 | 4,475,789 | 223,563 |

| 2014 | 2,774,661 | 4,620,756 | 224,616 |

| 2015 | 2,604,732 | 4,493,918 | 222,729 |

| 2016 | 2,612,833 | 4,381,101 | 238,326 |

| 2017 | 2,509,503 | 4,026,515 | 243,425 |

| 2018 | 2,632,260 | 4,265,525 | 244,103 |

| 2019 | 2,491,707 | 3,840,686 | 233,996 |

| 2020 | 2,470,776 | 4,059,911 | 255,568 |

| 2021 | 2,425,736 | 4,404,727 | 242,168 |

| 2022 | 2,056,118 | 4,445,255 | 235,851 |

| average | 2,535,719 | 4,301,418 | 236,435 |

| percent of total allocation | 90.6% | 97.8% | 78.8% |

Source: USBR decree accounting reports

I point this out as a native Californian, and with love for my California friends. The laws and policies we have developed allow – even encourage! – this. The doctrine of prior appropriation was designed to remove water from our rivers for “beneficial use”, emptying them in the process. California played a masterful game over the 20th century to ensure the priority of its water rights and the federal largesse needed to put the water to use.

But understand, please, why everyone else in the basin is glaring at you: you have a larger allocation than everyone else, and you’ve been reducing your use less than everyone else. The law gives your water use priority over others in the basin, but that doesn’t make it feel any fairer to the rest of us as everyone is being asked to cut back to save the shrinking river on which we all depend.

Boxed in

So where do we go now?

Despite the failure of the basin states to come up with a plan to reduce water use in 2023, and the unwillingness or inability of the federal government to impose one, the mass balance problem has not changed. The “protection volumes” – the amount of cutbacks needed next year and every year thereafter for the foreseeable future – are still huge. If the 2023 water year is similar to the last three, water users need to cut 2 million acre feet just to hold the reservoirs where they are and protect Lake Mead and Lake Powell from dropping to critically low elevations, according to the Bureau of Reclamation’s modeling.

Never mind about refilling.

According to a piece by Jake Bittle at Grist, California is working on a deal among the water users that would cut something – it’s not entirely clear what, Bittle references a range of 350,000 to 500,000 acre feet. This is super interesting in part because of the context – this is California going it alone. Yay for voluntary cuts! But it’s hard to see how the largest user on the system agreeing to cuts of that size gets us anywhere close to 2 million acre feet. But given the water politics within California, it’s also hard to see how California cuts more, at least voluntarily. Imperial Irrigation District is rightly demanding action on the Salton Sea, which has been shrinking as a result of past Imperial cutbacks. (Less irrigation means less percolation and runoff into the Sea. Bad air quality, bad mojo, as the Sea shrinks.) Getting Imperial farmers (and others, but Imperial’s the big player) to accept cutbacks voluntarily will have a big price tag. Forcing the cuts will almost certainly lead to litigation.

That leaves Arizona in a box. They’ve already cut nearly 800,000 acre feet this year, which is huge. There’s more water to be had in Yuma – again, for a price – but it’s hard to see Arizona coughing up more water absent California cutting more deeply. Where’s the fairness in that?

All the rest of us – Nevada, and the states of the Upper Basin – can do is look on in horror. I’ve been critical of the Upper Basin states for not agreeing to kick in some water, and I still think we’re going to have to do that sooner or later. But we’re only using ~4 million acre feet a year, on average, of our 7.5 million acre foot allocation. At this point, any savings we can muster are small relative to the use by California and Arizona. And given the Lower Basin states’ inability to come up with a plan, anything we do add to the system right now will just drain out the bottom in continued overuse.

Which leaves the federal hammer.

According to a press release last week, which (oddly?) came from the Department of Interior rather than the Bureau of Reclamation, Interior is preparing for the possibility that it may need to reduce releases from Glen Canyon Damn in 2023. (See Kuhn, Fleck, and Schmidt on this question.) This echoes something Reclamation said in August.

That would have the effect of further dropping Mead as Reclamation’s engineers scramble to protect Glen Canyon Dam.

Interior is also:

Preparing to take action to make additional reductions in 2023, as needed, through an administrative process to evaluate and adjust triggering elevations and/or increase reduction volumes identified in the 2007 Interim Guidelines Record of Decision.

I do not know what that means. I do not know if it is different from what Reclamation said in August, that the agency will:

Take administrative actions needed to further define reservoir operations at Lake Mead, including shortage operations at elevations below 1,025 feet to reduce the risk of Lake Mead declining to critically low elevations.

Folks in the federal government are frankly boxed in as well – between Lower Basin users unwilling or unable to cut use enough on their own to save themselves, with constraints imposed by a sincere attempt to be more inclusive of Tribal interests than the federal government has ever been, with the crazy problems of the Salton Sea hovering over any attept to rein in the basin’s largest water user, with the international challenge of including Mexico in the coming decisions, and with a crucial mid-term election looming.

So far, those constraints have prevented the federal government from getting specific about the threats – at least in public.

It’s hard to look at all these constraints, the boxed-in-ness – on Arizona, on California, on the federal government – and not see dead pool looming.

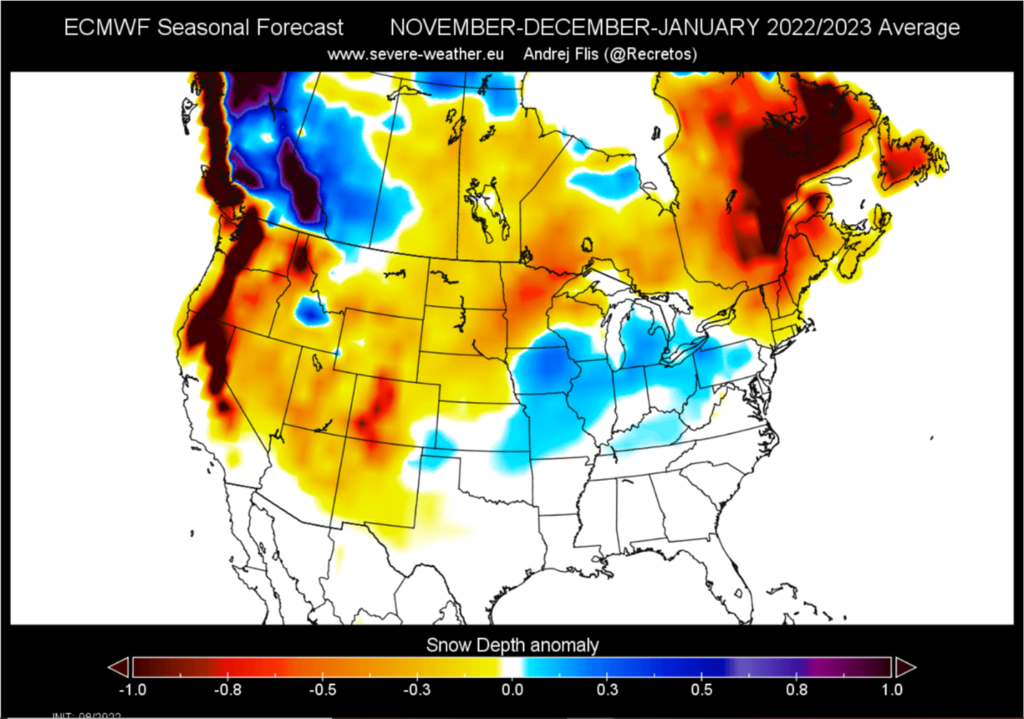

Absent a big snowpack, I don’t see how this ends well.