There’s a tangent in Henry Brean’s Las Vegas Review-Journal story about desalination and Las Vegas this morning that provides a reminder of just how far we’ve come in the power structure surrounding the management of the Colorado River in the last century.

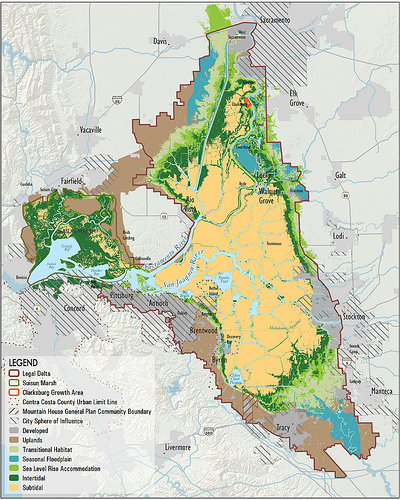

Morelos Dam, on the US-Mexico border, where the Colorado River for all practical purposes ends

The main thrust of the story is a discussion of the possibility of coastal desal as an alternative to the controversial Las Vegas groundwater pipeline proposal. Pipeline opponents have been arguing that desal is a reasonable alternative – not directly, but through water swaps through which Vegas would fund coastal desal for California or Mexico water users, and get a share of their Colorado River water in exchange.

The tangent is this: Brean quotes Mexican official Jose Gutierrez on how “fiercely” Mexico will defend its share of the river – a share that’s frankly paltry. Its 1.5 million acre feet of water is roughly ten percent of the river’s flow. Given how little Mexico gets, that ferocity is understandable. It also makes it hard to believe that there was a time when US water users feared Mexico would dominate the river’s allocation. But in the 1920s that was, in fact, the case.

One of the great early Colorado River water management histories is a doctoral thesis done by Reuel Leslie Olson in 1926 – after the Colorado River Compact was signed, but before any of the big infrastructure was built to begin moving water around. It’s a fun read because it captures a lot of early uncertainties about things that have long since been settled in ways that in hindsight seem inevitable – as, for example, Mexico getting largely screwed in the allocation of Colorado River water. From the vantage point of the mid-’20s, it seemed anything but inevitable.

At the time, the water needed to irrigate the Imperial Valley flowed through Mexico on a looping path before heading north. There was pressure to build an “All American Canal” (which has long since been done) because of fears that the southern California farmers were at the mercy of Mexico for their water. In fact, it was U.S. landowners in Mexico, most famously Harry Chandler of the LA Times, who were providing the pressure for a larger Mexican share of the river. Here’s Olson:

Mr. George H. Maxwell, long interested in irrigation problems, declares that a great part of the trouble encountered in present plans for development of the Colorado River, arises from the fact that much is now being done to attempt “to nail the Colorado River down for Mexico.”