I first noticed it while I was out in the mountains of northern New Mexico back in the mid-1990s with Karl Karlstrom, a University of New Mexico geologist. I had tagged along on a summer field camp mapping exercise for a feature I was doing, and spent a good part of the day shadowing Karl and some of his students as they mapped a tangled section of old basement rock.

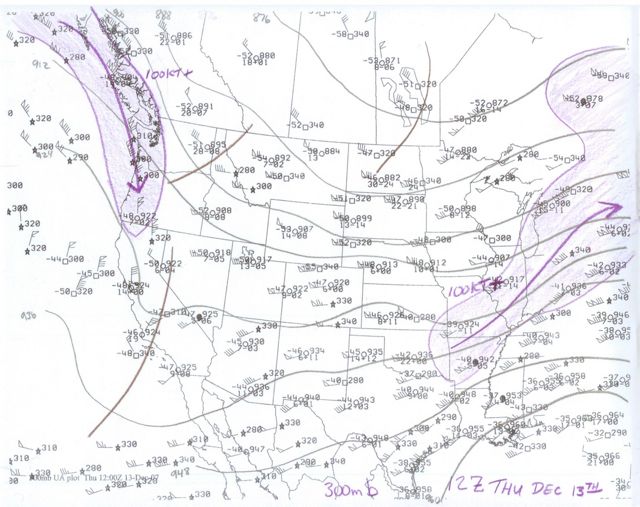

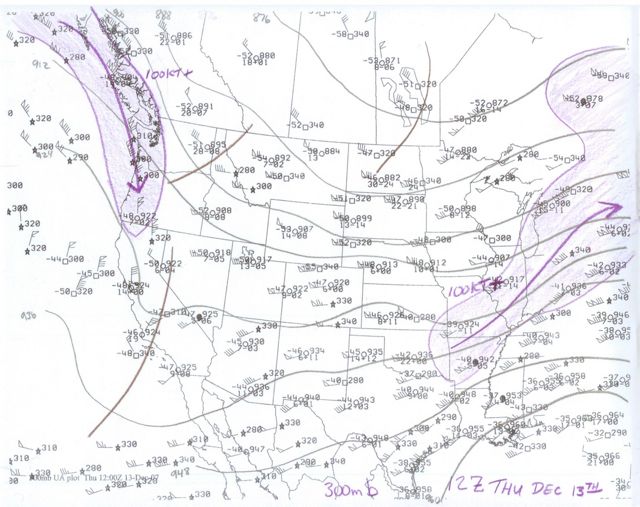

Hand Drawn Weather Map

This will be familiar to earth scientists, but was a revelation to me – the way Karl with his little pouch of colored pencils sketched in the rock units as he walked. He was not simply recording data. The act of drawing was part of his construction of a mental model.

I’ve seen it again many times, most notably among meteorologists. In my book *, there’s a scene with forecaster Ken Drozd sketching out the movement of a storm across his daily weather map. Charlie Liles, the retired head of the Albuquerque Weather Service office, used to make these wonderful colored drought maps by hand.

*, there’s a scene with forecaster Ken Drozd sketching out the movement of a storm across his daily weather map. Charlie Liles, the retired head of the Albuquerque Weather Service office, used to make these wonderful colored drought maps by hand.

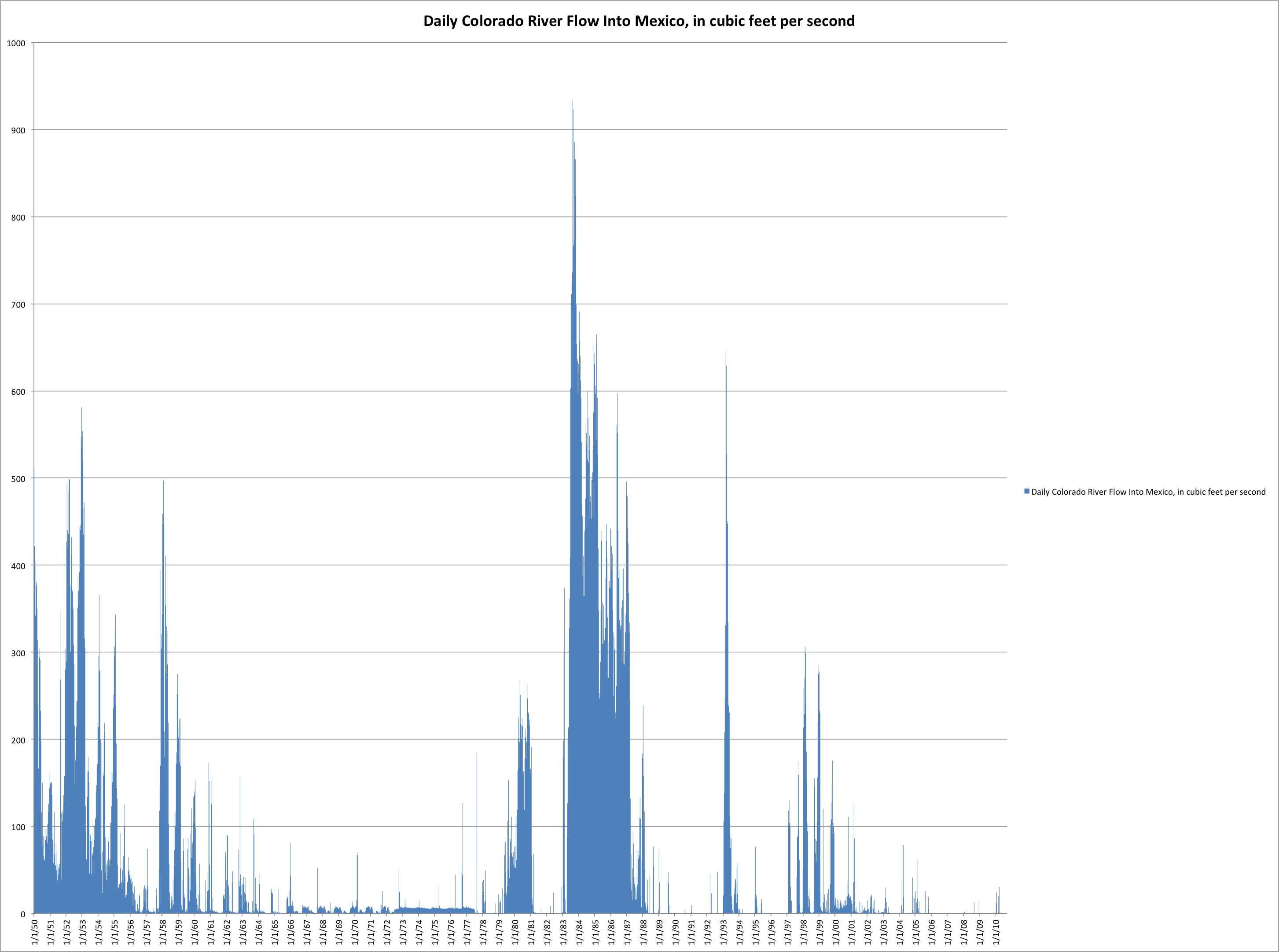

Tom Pagano, the roving river forecaster, has a thoughtful explanation today on his blog about why it’s done this way:

Even though they have access to some of the largest supercomputers in the world, somewhere right now a meteorologist is sitting down with a set of colored pencils to hand-draw air pressure levels on a blank map. This is a generational thing, for sure, younger forecasters (myself included) often preferred to automate things and spend more time, for example, actually getting to eat lunch.

However, it is a meditation on the data. They spend time with their problem, giving it attention and thinking about its parts. As they draw, they consider each individual curve and line, while also subconsciously (or even consciously) marinating in the meaning of the broader pattern of the data. They are developing and exercising their intuition.

I’ve wondered too about whether it’s a generational thing. For the meteorologists, geologists and anyone else in the audience, do you sketch out your work by hand?

* Ideal for that bright youngster on your holiday shopping list!