FYI, I’ll be at the Colorado River Water Users Association meeting in Las Vegas next week, if any of the water wonks out there will also be in attendance and wanna get together, maybe go throw rocks in the Bellagio Fountain or something?

Measuring the snow

When I was thinking about how to write a book about climate science for kids, measuring the weather made sense to me. As a journalist, it’s my favorite science to write about because of the opportunities to tie science to everyday experience. And any kid can set up a thermometer and rain gauge in their backyard and do science for themselves.

That’s why I packed The Tree Rings’ Tale with hands-on activities. (It’s not just about dendrochronology.)

Take your ruler with you outside. Look for places where the snow has fallen on a flat surface, like a picnic table or the top of a car. It should be away from buildings. Stick the ruler straight down through the snow. Note the height of the top of the snow on the ruler. Take three measurements, noting them in your journal.

I’m big on keeping a journal.

My fondest hope for this book is that somewhere this morning, kids who read it are out measuring.

Available through Amazon, or if like me you’re partial to hanging out at your local bookstore, check to see if they can get you a copy. My new favorite, Alamosa Books(disclosure: daughter works there) had a few signed copies left when I was in there Friday.

Bay-Delta salinity – a brief history

Thanks to Controversy (the Journalist’s Best Friend), the subject of salinity in the Sacramento-San Joaquin-San Francisco Bay Delta system has received more attention of late than is usually attached to such arcane topics. But I did not realize how old this issue is.

courtesy Delta Stewardship Council

It was salinity and fish science that caused federal Judge Oliver Wanger to famously tee off on a pair of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service scientists back in September. The underlying issue is that water removed from the Sacramento and San Joaquin systems that would otherwise have reached the estuary between fresh and salt water changes the system’s salinity. More fresh water flowing to the sea pushes salt water out of the system. Less allows the salt water to flow back in, through Suisun Bay and into the delta. This plays a role in the life history of the endangered delta smelt, which makes salinity a pertinent question in California’s tangled water management these days.

As Felicity Barringer explains it:

The area of ideal salinity for the smelt shifts back and forth, eastward and westward, depending on the time of year, the amount of rain and the decisions of federal and state water managers. (A fuller explanation with diagrams can be found at the Bay Delta Blog.)

This zone of ideal salinity for young smelt to feed is known as the X2; the Interior Department had decided that in wet years like this one, it should be no farther than 46 miles east of the Golden Gate Bridge. The decision was challenged in the lawsuit by the state and agricultural water interests, which prefer that less go out to the bay.

Pronouncements by two federal scientists on the issue drew Wanger’s ire, which made salinity the hot combat science topic of this past fall in California politics. But I was struck in reading Philip Garone’s environmental history of California’s Central Valley to learn how long this problem has existed.

The first irrigation diversions upstream of the delta date to 1852, and by the 1870s enough water was being taken out of the rivers to make a noticeable change in the delta. As rice farming expanded, the problems increased:

When a record 164,000 acres of rice cultivation coincided with a serious drought in 1920, the salinity problem in the Delta reached crisis proportions. In July of that year, the western Delta city of Antioc, situated near the mouth of the San Joaquin River, together with ninety-seven Delta landowners, brought suit against upstream irrigators in the Sacramento Valley. The plaintiffs requested that the irrigators be enjoined from diverting so much water from the Sacramento River and its tributaries that tidal salinity would advance far enough into the Delta to threaten Antioch’s municipal water supply, which was drawn from the San Joaquin River.

Antioch lost, the court ruling that it had no right to unsalted water if that meant someone upstream had to stop diverting. But efforts to deal with the issue in a long term fashion, Garone writes, eventually led to the creation of the Central Valley Project. Which is what led federal scientists back into court this year talking about salinity.

Yo! Over here! Not much water in the Colorado River! What should we do?

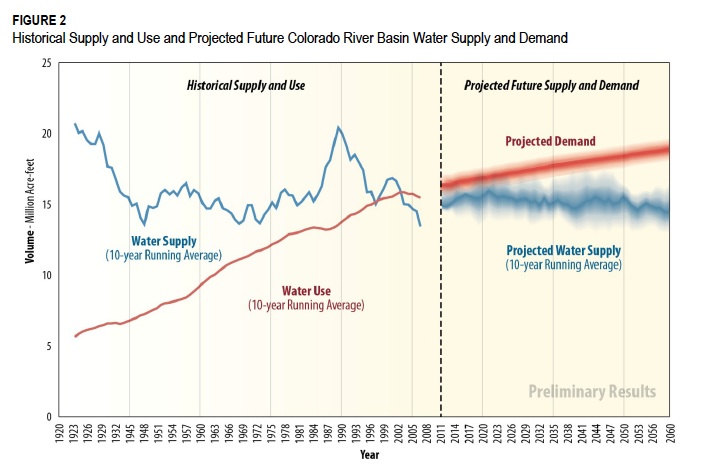

The folks working on the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study last week published a striking new graph (figure 2 in this pdf) pointing out our dilemma:

It’s an attempt to splice together the latest version of the Bureau’s now-ubiquitous graph of historical supply and demand with the latest projections from the agency’s ongoing Supply and Demand Study. The crisp-looking bits to the left of the dotted line are what we know has already happened. Note the supply and demand curves converging in the late ’90s as Arizona finally starts using its share of Colorado River water. The fuzzy bits to the right of the dotted line, as the curves diverge, are the sternly caveated projections starting to squeeze out of the Supply and Demand Study.

In brief:

- Demand: 17 million acre feet by 2035, 18 million acre feet by 2060

- Supply: 15 million acre feet by 2035, 14.4 million acre feet by 2060

You’ll note that the demand numbers are larger than the supply numbers. If you have any suggestions re fixing this, the Bureau would like to hear from you.

Stuff I helped produce elsewhere: tumbleweed snowman

In New Mexico, we make our snowmen out of the materials at hand:

(updated with a link to the video because I can’t figure out how to embed it right)

Does access to water make you more vulnerable to drought?

It might seem obvious that the more water you have available, the less vulnerable you are to drought. Or not so obvious?

Comparing counties over the Ogallala with nearby similar counties, groundwater access increased irrigation intensity and initially reduced the impact of droughts. Over time, land-use adjusted toward water-intensive crops and drought-sensitivity increased; conversely, farmers in water-scarce counties maintained drought-resistant practices that fully mitigated higher drought-sensitivity.

That’s from Hornbeck and Keskin, The Evolving Impact of the Ogallala Aquifer: Agricultural Adaptation to Groundwater and Climate.

The changing duty to bear witness

I don’t know who “qbertplaya” is, but I am eternally thankful to him or her for this:

It’s Patti Smith closing CBGB, the last song played there, a moment in history captured by someone wise and generous enough to hold up some sort of mobile recording device. I was struck by that act when I first ran across the recording years ago – the difference between being in a moment and recording it for others.

It is a long and important tradition that includes the strange story of Abraham Zapruder. But like qbertplaya, we are all Abraham Zapruders now. In the now-famous picture of a University of California Davis police officer pepper-spraying peaceful seated demonstrators, I counted 15 people taking pictures, outnumbering those who were not filming.

There’s an odd sort of detachment in the act of bearing witness for posterity instead of simply being in the moment. I know it professionally. I’m not a photographer, but I’ve been rethinking this because I’ve started taking pictures in my newspaper work recently. That fundamentally changes what has always been, for me, the act of bearing witness. Being at a “thing” when I’m working is different, the way I try to see more, remember and annotate and prepare for the retelling even as I’m experiencing. Instead of just being there and enjoying.

I thought of this anew yesterday when I reread, on the news of his death, Tom Wicker’s remarkable first-day story on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. As an example of tradecraft, it is a thing to behold – richly detailed yet unadorned, famously dictated from a pay phone “from notes scribbled on a White House itinerary sheet.” It is impossible as a practitioner for me to read the work of others without pondering the “how did they do that” question. It is impossible for me to watch Wicker bear witness that day and not be in awe:

Standing beside the new President as Mr. Johnson took the oath of office was Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Her stockings were spattered with her husband’s blood.

this is a test

This isn’t the blog post you’ve been looking for.

“focused, not fighting”

The Arizona Republic had a very smart editorial today about the Colorado River. The premise: what happens in California matters a great deal to Arizona. The back story is a struggle in California about how to meet the terms of a deal in the early ’00s to cut back to its 4.4 million acre foot share of the Colorado River after years of overuse. Californians are in court now fighting over the details of how to do that. It would be easy for the other Colorado River states, especially Arizona, with its long history of fighting with Californians, to watch from a smug distance, maybe even take quiet pleasure in California’s discomfort. But the Republic wisely notes this:

[A] California in turmoil, unable to manage a limited supply of water efficiently and perhaps casting about for other sources, will be a poor partner in future water planning.

And we need a lot of planning. The Colorado basin is in a decade-long drought, with predictions for a hotter, drier future. A study is under way to figure out how to supplement the river’s water supply, maybe through desalination or importing water or cloud seeding.

We need California to be focused, not fighting.

A tip of the Inkstain hat to the unmissable Aquafornia for the link.

Dipping more drinking straws into the Colorado River

When it comes to water, we westerners seem to be a distrustful lot:

Water politics in Colorado and in western Wyoming have long been driven by this one, nagging fear: that California was getting something to which it was not entitled – and might get accustomed to it. Squatter rights, if you will, bolstered by a huge population advantage. Million still plays that card. “If the water users of Wyoming decide they don’t want to access their water, then that’s their decision – and California, Arizona and Nevada will continue to benefit,” he says.

Stacy Tellinghuisen, water and energy analyst for Western Resource Advocates, says she believes proposals for pipelines at Flaming Gorge, Lake Powell and Las Vegas are all driven by a new realization of limits. “The thinking is that if we develop this now, if there is a shortage in the future, we will still have this water,” she says.

That’s from Allen Best’s sweeping look at proposals by entrepreneur Aaron Million and others to siphon off some more water from Flaming Gorge. Beyond the narrow point I’ve selected, the piece richly rewards. If you’re interested in western water, I recommend giving it a click and a few minutes of your time.