Some more odds and ends from last week’s Colorado River Water Users Association meeting

Water in the Desert, Caeser's Palace pools

Yuma Desalting Plant

The trial run of the Yuma Desalting Plant “went well,” according to Terry Fulp, head of the USBR Lower Colorado office. YPD was built in the early 1990s to clean up icky agricultural drain water to meet US delivery obligations to Mexico, but it’s never really been used until a trial run in 2010-11 intended to see what it might take to put it to use. According to Chuck Cullom of the Central Arizona Project, one of the YPD trial run’s funders, the operational costs worked out to about $300 per acre foot of water for the 30,000 acre feet produced during the trial run. That makes it relatively expensive water. Fulp said one of the things they learned is that major infrastructure upgrades would be needed to move beyond the trial phase into routine operation.

Brock Reservoir

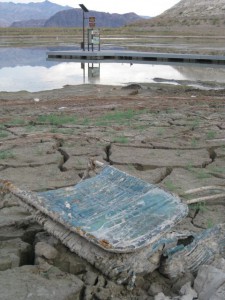

The Brock Reservoir, formerly known as “Drop 2”, “saved” 110,000 acre feet of water in the 2011 water year. Brock’s purpose is to capture water released from Lake Mead but then not needed by Imperial Valley farmers because it rains. Such water was “wasted” because it would flow on to land formerly known as the Colorado River Delta unused by humans, though it’s worth noting that one person’s “waste” is another person’s “environmental flows”.

Environmental Flows

Worth noting – the discussions about YDP and Brock both expose the significant unresolved conflict between water development and the growing recognition that environmental flows need to be part of the discussion as we divide up the increasingly stressed Colorado.

Water for Mexico

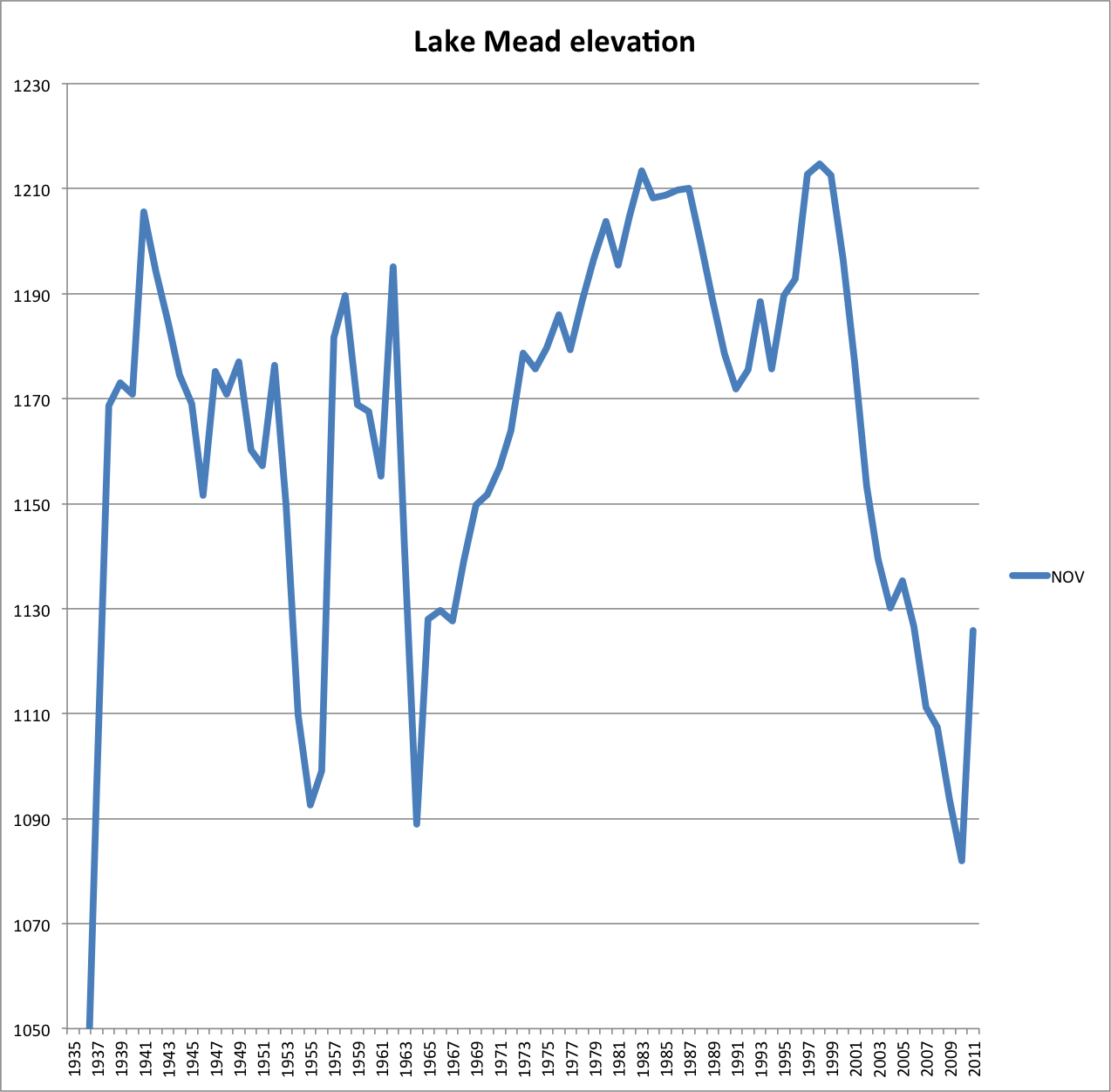

50,000 acre feet of Mexican water is currently being stored at Lake Mead as part of an agreement that for the first time allows the Mexicans to take advantage of storage behind U.S. dams. This is being done after the April 2010 Mexicali earthquake damaged irrigation canals there. It seems like a very important first step toward some broader cross-border water management.

Still moving last year’s water

The Bureau of Reclamation continues to run Glen Canyon Dam’s power full bore to move last year’s bounty downstream. There was so much inflow that the dam’s power plants have been running all out for months.

Navajo-Gallup

We should see a request for bids soon (by the end of this month) on construction of Reach 12A of the Navajo-Gallup water supply project, which will ultimately connect the eastern Navajo Nation to San Juan River water. This is the first length of pipe on the project, and would in the near term carry groundwater. The US Bureau of Reclamation was really pushing this project at the meeting. “We’re bringing drinking water to people who are still hauling it to their homes,” Anne Castle, Interior’s Assistant Secretary for Water and Science, said during one of the meetings. But it’s also clear that finding money for the full project in the long term will be a challenge.

Protect the Flows

Molly Mugglestone of Protect the Flows gave an interesting presentation on the relatively new organization’s work. It’s a growing coalition of businesses that depend on water in the river – fishing guides, rafters, tourism-based businesses of various types. It’s the business-economic case for instream flows.

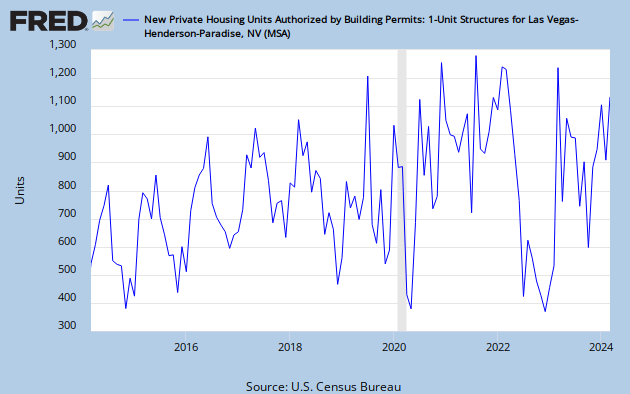

Las Vegas

Did I mention that Las Vegas (NV) is a very strange place? But well lit.