I’d have to call Emma Marris’ The Rambunctious Garden the most influential book I read in 2011, in large part because it fell on fertile ground.

the most influential book I read in 2011, in large part because it fell on fertile ground.

Budgerigar, December 2011

I’ve been puzzling for a long time over the question of what counts as “nature”, both in our political discourse and in my own heart of hearts. Why is it, I’ve long puzzled, that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge represents land worth laying down on the tracks to protect, but not the patch of what used to be desert scrub that is now my very much altered backyard?

I’ve mulled this issue for a long time, but it’s mostly been an inchoate puzzlement. Maris, in her treatment of the history of our cultural ideas about wilderness and preservation and current ecological science, put some meat on the bones of the ideas. As did our neighborhood budgerigar, a feral parakeet that’s been hanging around of late.

I spotted one in the neighborhood a couple of years back, and this year I’ve got four sightings on my yard list – in July, November and twice this month. The budgie’s clearly “unnatural”, an escaped or abandoned pet. But what, exactly, does that mean? My 2011 yard list includes pigeons, house sparrows, starlings and Eurasian collared doves – none of them native to North America, all feral immigrants that hitched a ride in some fashion with humans to get here. The difference is that, on arrival, the latter birds did better.

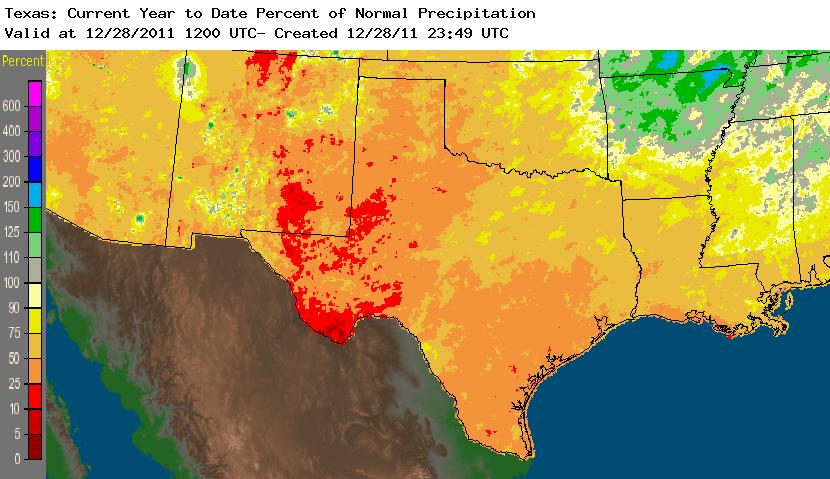

My backyard is similarly unnatural, with five different types of feeders and a pond for the birds. It’s a xeric garden, with plants adapted to the arid climate, but we do add more water than nature would otherwise provide. We’ve got a pear tree.

The budgie seems to be well across the line separating natural from unnatural, but as you pull back toward the center it’s not clear where the boundary lies.

What Maris makes clear is that the boundary is a human construct, that there is no untrammeled wilderness but rather a world of ecosystems bearing a world of human footprints.

Which is a long-winded way of introducing my 2011 Yard List – 40 species of birds this year, plus one mysterious swallow. Three were new to my yard life list:

- red-winged blackbird

- house wren

- dusky flycatcher

That brings my yard life list to 59.

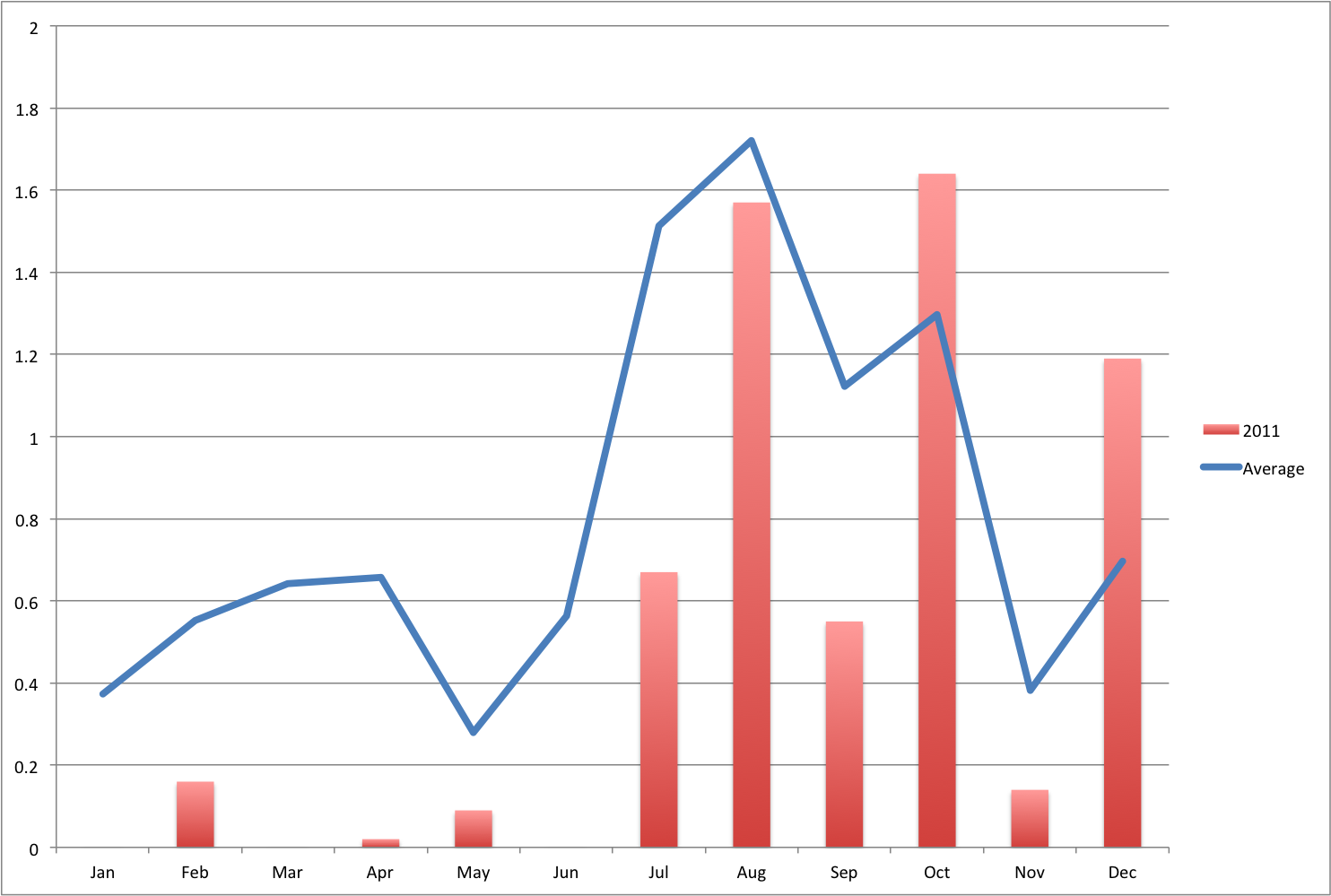

This year’s ecological puzzle is the mourning dove, which was ever present in 2008 (that’s when I started listing), ’09 and ’10, but is now only an occasional visitor. A second ecological puzzle is the pigeon. A flock lives at the supermarket and Indian restaurant two blocks away, but until this year they almost never came to my yard. They’re regulars now. I don’t mind. I’ve always been a bit of a pigeon fan. Sadly our state bird, the roadrunner, was a rarity this year. Click through for my year’s yard list. The numbers represent the percent of observations for which the named bird was present.

Continue reading ‘The year of the budgie’ »