Lake Mead, December 2011, by John Fleck

Climate scientist Tamsin Edwards triggered a fascinating discussion when she chose the famous George Box quote – “all models are wrong, but some are useful” – as the name for her new blog. In a delightful exchange on Twitter (which I followed in real time and which Edwards quotes extensively in the blog post linked above), Peter Gleick chastised Edwards for choosing “All Models are Wrong” for the title of her blog, arguing that it “buys into ‘everything is uncertain’ meme.” Edwards pushed back, and I tend to agree with her argument – that acknowledging and thinking well about uncertainties is incredibly important for the climate discussion to move forward.

I’m reminded of the problem exemplified by the news coverage (mine included) of the US Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Study:

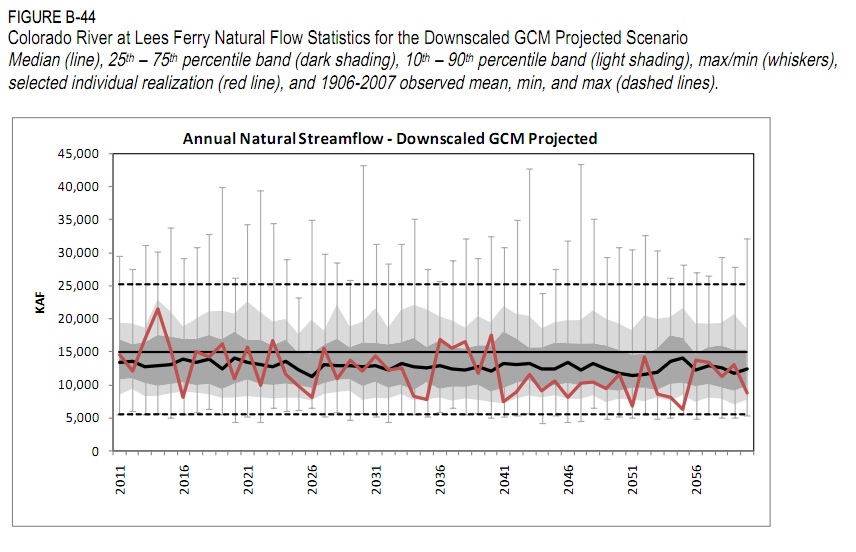

A new federal study released in conjunction with the conference forecast that the Colorado could have 9 percent less water on average by 2050 as a result of climate change, with persistent drought growing more common.

That 9 percent figure has become the study’s frequently repeated headline number. It’s significant in part because the Bureau of Reclamation, which in the past has been criticized for not including climate change risk in its long term water management modeling, ponied up this time. But is it the right way to think about this?

A new paper* by B.L. Harding and colleagues (researchers working on the Basin Study) makes a more subtle argument (and takes a dig at my profession for the way this question has been treated):

By the middle of the century, the impacts on streamflow range, over the entire ensemble, from a decrease of approximately 30% to an increase of approximately the same magnitude. Although prior studies and associated media coverage have focused heavily on the likelihood of a drier future for the Colorado River Basin, approximately one-third of the ensemble of runs result in little change or increases in streamflow.

If the models come up with such a broad range of answers, then by definition most of them are “wrong” in some sense. But they still seem to be quite useful here, just in offering something other than a prediction.

Suraje Dessai and colleagues wrote a really interesting book chapter back in 2009 (pdf)** on “the claim – explicit or implicit – that decision-makers need accurate, and increasingly precise, assessments of the future impacts of climate change in order to adapt successfully.” This is exactly the sort of thing we have seen here in the western United States – a push to refine the modeling to give us a better handle on the effect of climate change on the Colorado River. There’s nothing wrong with that other than the notion that we’re trying to settle on a number.

Suraje Dessai and colleagues wrote a really interesting book chapter back in 2009 (pdf)** on “the claim – explicit or implicit – that decision-makers need accurate, and increasingly precise, assessments of the future impacts of climate change in order to adapt successfully.” This is exactly the sort of thing we have seen here in the western United States – a push to refine the modeling to give us a better handle on the effect of climate change on the Colorado River. There’s nothing wrong with that other than the notion that we’re trying to settle on a number.

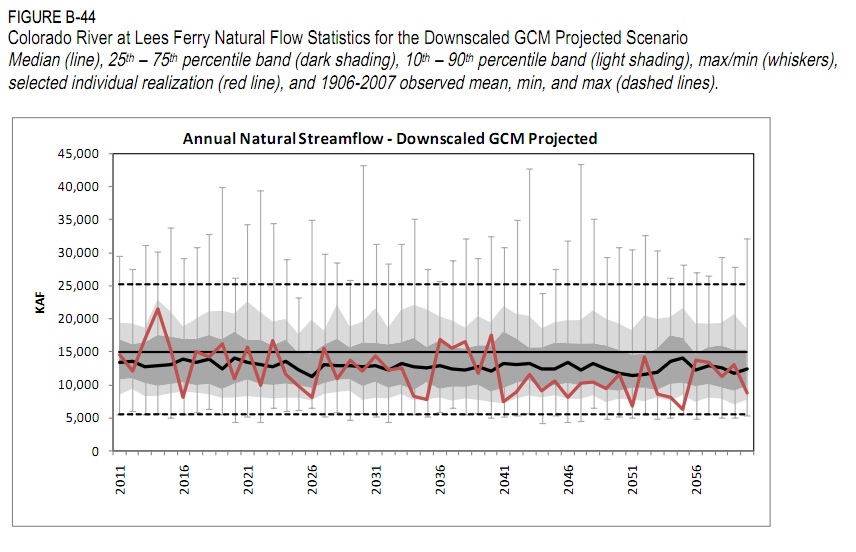

The point of Harding et al. is that we shouldn’t expect to know something meaningful by simply averaging across all the model runs and offering up a single numbers. If you dig into the bowels of the Basin Study report (pdf, see especially figure B-44), you can see the models spitting out not a single number, but a range of possible futures. (The majority of them are drier futures.)

These models are useful precisely because they help us think about the range of uncertainties that the region’s water managers face. From Dessai et al.:

We suggest that decision-makers systematically examine the performance of their adaptation strategies/policies/activities over a wide range of plausible futures driven by uncertainty about the future state of climate and many other economic, political and cultural factors. They should choose a strategy that they find sufficiently robust across these alternative futures. Such an approach can identify successful adaptation strategies without accurate and precise predictions of future climate.

To the extent that we communicate this with anything other than a genuine respect for the uncertainty, we do the public and the policymakers who have to figure out how to manage the Colorado River a disservice.

* The implications of climate change scenario selection for future streamflow projection in the Upper Colorado River Basin; B. L. Harding, A. W. Wood, and J. R. Prairie, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 9, 847-894, 2012w, doi:10.5194/hessd-9-847-2012

** Climate prediction: a limit to adaptation? Suraje Dessai , Mike Hulme , Robert Lempert and Roger Pielke, Jr., in Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance, eds. W. Neil Adger, Irene Lorenzoni and Karen L. O’Brien. Published by Cambridge University Press, 2009