What we call here the “water year” runs from October to the end of September. It’s a useful tool, capturing the fall-winter-early spring water collection season, in which snow builds up in the mountains for later use by humans and ecosystem, followed by the water use season. So the end of March is a nice point at which to take stock.

At my house, I’ve received 3.9 inches (9.9 cm) of precip since Oct. 1, which is dead on the long term average to within the measurement error on my backyard gauge. My precip has largely come in two wet spells, one in October and a two week stretch in December when the storm track inexplicably dropped down on top of us. For a La Niña year, when odds favor dry, I’d say an average first six months counts as excellent news.

But it’s clear that won’t sell. Luis Villa last night pointed to an excellent talk by the ‘net scholar danah boyd about fear and the attention economy. The “attention economy” is the notion that all these ideas are flying about the ‘net in tremendous volume, with eyeballs as the currency, and fear sells. So if I were to try to get your attention using fear attention economy tactics, I might show you something like this:

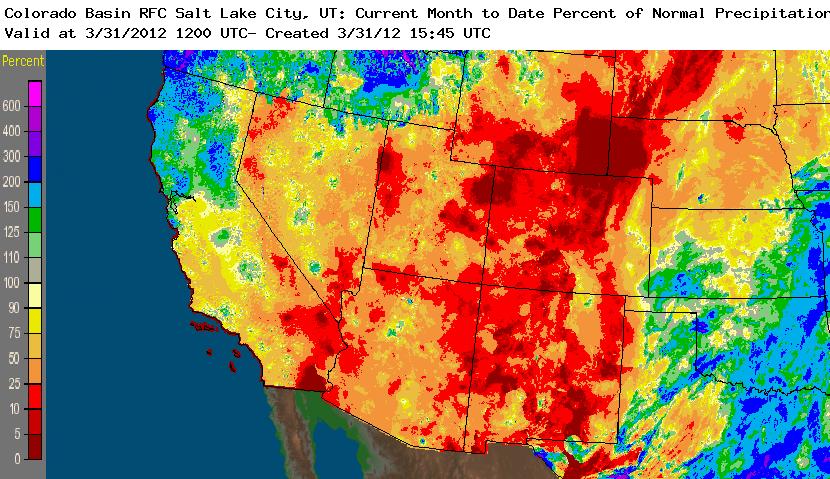

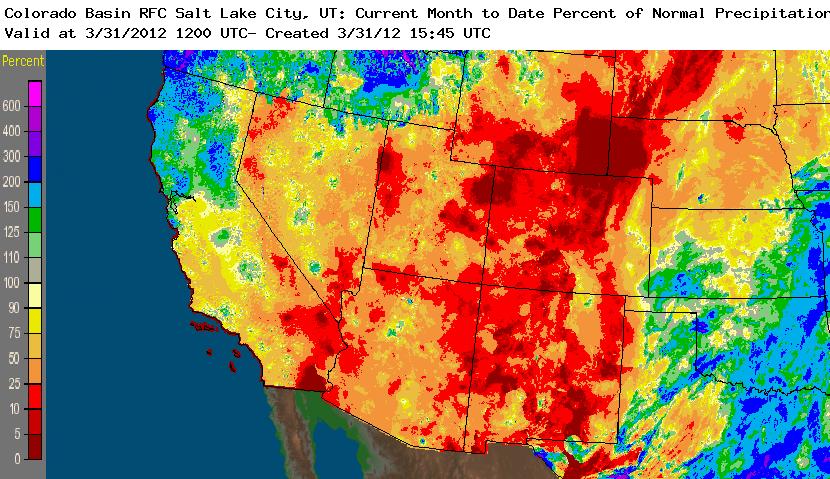

March 2012 precip, percent of average

That’s percent of normal March precip via the Weather Service’s Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service. Check out the color scheme. These folks get the fear economy.

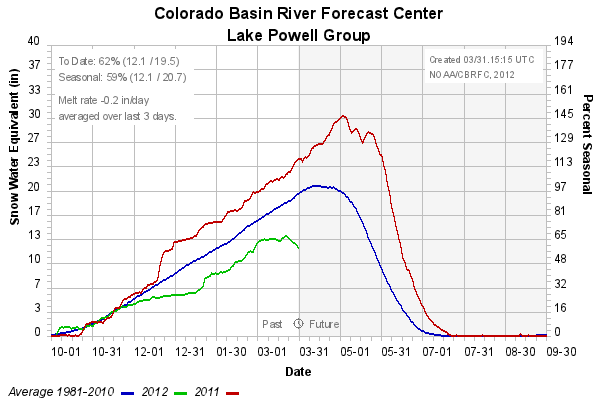

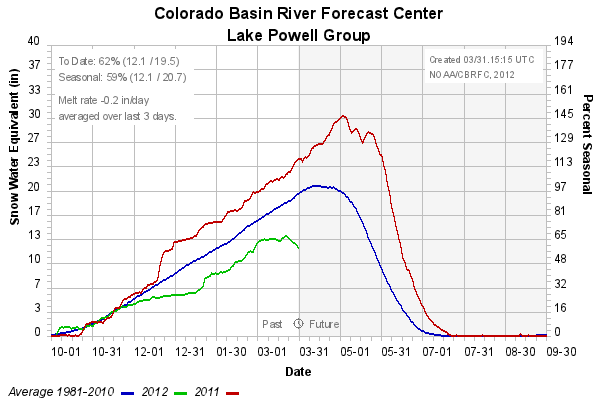

Or this, which is NRCS snowpack data above Lake Powell (essentially the whole Upper Colorado Basin) as assembled and shared by the NWS Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. The fear economy tactics are a bit more subtle, but see that diving green line? That’s snowpack dropping a month early. Normally during March it goes up. This year it has not. I check this every day and it scares me and makes we want to check it again tomorrow. The fear attention economy in action.

Colorado Basin Snow group

Or less fearfully, Lake Mead’s currently up 33 feet from last year at this time, because some years are wet while others are dry, and during those wet years we spend some of our water filling the reservoirs so we have water to use when it gets dry. (Note that I had a hard time finding a non-fearful picture here, because even those from my latest visit to Lake Mead last December still show a big bathtub ring despite the rising levels.)

Lake Mead, December 2011