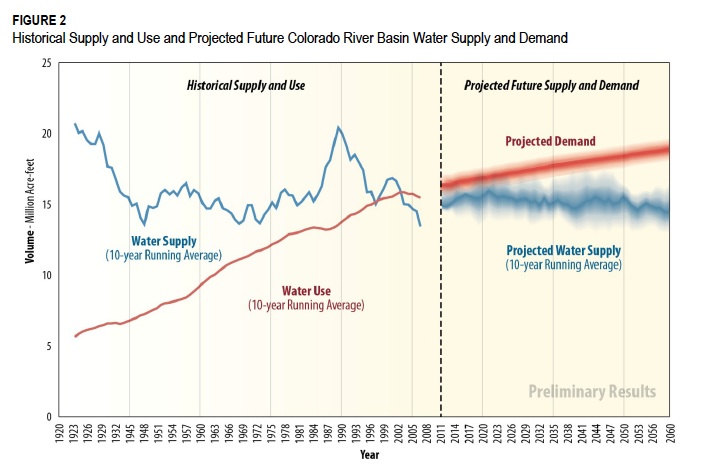

In the work I’m doing now on the Colorado River Basin for my book, I’m trying to get beyond simply extrapolating supply and demand curves and then running around with my hair on fire. The hair-on-fire thing is easy to do, because the current supply and demand curves, as the Bureau of Reclamation frankly noted last December, are heading in a direction that’s physically unreal.

The question is what happens in the gap between the projected orange line veering upward and the blue line veering down. I’m interested in the specifics of that failure mode – who will come up short as the gaps between supply and demand become real, and how might we expect them to respond? It’s not enough to simply say “Phoenix (or Las Vegas or Los Angeles or Denver or the Imperial Irrigation District or Albuquerque) is screwed.” Because those water users will do something in response to try to minimize their screwedness. Who are they, and what will they do in response?

Buried in the tiny print of the US Bureau of Reclamation’s latest 24-Month Study (pdf) is a hint about what seems to me to be the most likely answer to my “who” question: Las Vegas, look out. (warning, wonkiness ahead, click through for more)