Barry Nelson had an insightful post today comparing and contrasting the Colorado River and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay Delta systems. There are important similarities – crashing (or crashed) ecosystems and water supplies for human systems that are stretched beyond the point of sustainability. But the institutional frameworks for addressing those problems and the prospect of solutions arising from those frameworks are very different.

Lee's Ferry, 2005

Oddly, as Nelson lays this out (and I agree), California in some sense has more institutional momentum behind grappling with core questions in the delta than one sees on the Colorado River. Yet I would argue (and this is me, not Nelson) that the chances of solving the Colorado River’s problems are much more realistic than the Delta.

On the Delta, Nelson points out via the recent Delta Vision report card that near term actions, things like levee upgrades, are stalling:

The Foundation also concluded that “the level of effort is impressive” on Bay-Delta issues. Why the apparent conflict between these two conclusions? In short, the Foundation concluded that there is a tremendous current investment in efforts to develop long-term solutions through the BDCP and Delta Plan programs, but that short-term actions like improving Delta levees and beginning ecosystem restoration are proceeding far more slowly than is needed.

I’d argue that the level of accomplishment is not commensurate with the level of effort on the long term Delta solutions either.

Compare this now with the short term and long term situations on the Colorado. As Nelson points out, short term successes on the Colorado are substantial:

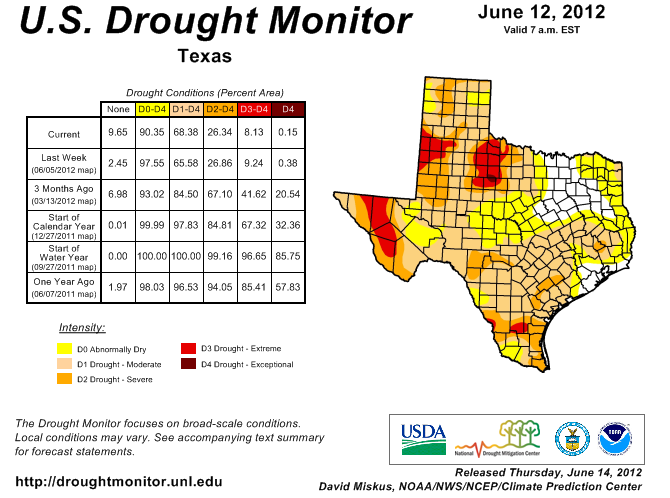

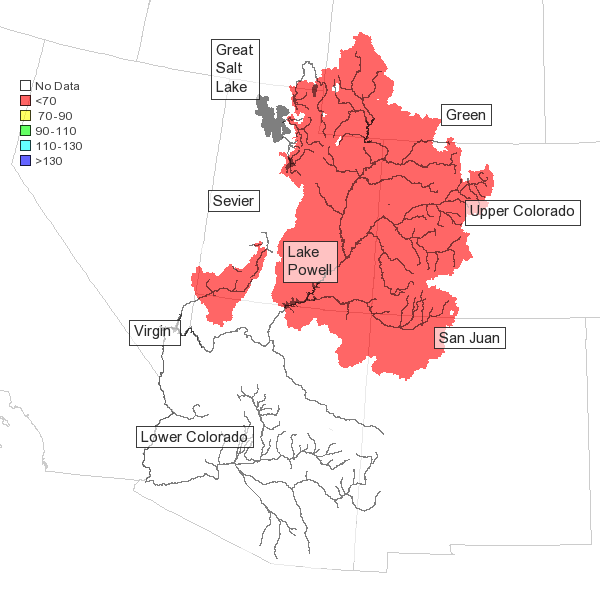

In recent years, a great deal of effort has gone into developing near-term water management solutions, in light of the decade-long drought on the Colorado. Among these near-term solutions are water banking agreements between Nevada and Arizona and the Bureau of Reclamation’s interim guidelines regarding the allocation of shortages in the Lower Basin.

But what about the long term on the Colorado? Nelson:

The Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado River Basin Supply and Demand Study is putting the long-term challenges in sharp focus. The Bureau’s conservative interim conclusions paint a stark picture of the challenges that would result from a status quo approach in light of the likely impacts of climate change on the available water supply in the basin.

The problem, as Nelson notes, is the lack of a framework for dealing with the grim numbers coming out of the Basin Study:

What I find interesting is that there is no well-established forum to address the Bureau’s findings that includes federal agencies, as well as all of the Basin states, water agencies and stakeholders. In short, there isn’t a well-established and comprehensive Basin-wide forum to pick up the ball from the Bureau’s Basin Study. Given the size of the basin, the diversity of the players and the scale of the challenge, such a forum is likely to be critical to developing and implementing a sufficiently ambitious long-term plan.

Shorter Nelson: Delta – big institutional framework, lack of progress. Colorado River – progress, but not much framework.

This is the same issue lingering behind Carpe Diem West’s Governing Like a River Basin report. As I wrote then, there are a variety of possible governance frameworks that might be used to begin tackling the big picture Colorado River problems…

But what remains … is the meta-process question. By what process involving the existing institutions we’ve got will some sort of solutions-oriented new process arise?

I actually am more optimistic about such a meta-process arising organically than I was when I wrote the above sentences back in December. I’m sure that some sort of uber-process-framework creation, along the lines of BDCP in California, won’t work. But Nelson noted something important regarding Colorado River processes:

I was … struck at a recent Colorado River conference by the commitment among agencies and stakeholders to develop workable interim solutions and to develop relationships that set the stage for more far-reaching long-term efforts.

I see that too on the Colorado. On the Delta, not so much. That’s the key difference.