tl;dr I started this blog 20 years ago today. I used it to learn to write.

Why?

Tims 20th birthday cake, courtesy Marion Doss

This blog started 20 years ago today (March 9, 2003) thus:

I have too many blogs already – Advogato, the Nuke Beat, my ABQJournal musings. Starting another seems a bit of overkill. They all have their roots elsewhere – a pre-existing publisher in the case of the Journal and Advogato, which provides a built-in audience. There’s comfort in that. The Nuke Beat’s just a hare-brained experiment, which may or may not work. But they all have something in common, which is me.

By that time I’d been a professional writer for two decades, for most of that time solely in print. My nerdy volunteer side hustle working on free software (GNOME, a Linux user interface thingie) took me down the tech rabbit hole, and I was part of the newspaper geek crew trying to figure out how make sense and use of the Internet’s amazing possibilities.

As the quoted bit above notes, I’d already been experimenting with blogging – Advogato was a free software community site, the Albuquerque Journal gave some of us blogs to play with early on, and I’d set up the “Nuke Beat”, a topic-specific blog associated with the nuclear stuff I was covering at the newspaper and as a freelancer at the time.

But none of them were “me” exactly – all were derivative of some particular subset of what I was writing and thinking about.

Rob Browman and I had registered the Inkstain domain name some years earlier and were already using it as a sandbox, first with a little Sun box plugged into a rack of gear at the office, then hosted at Southwest Cyberport, our still-awesome local ISP.

Inkstain began with two mottos: “Some things you don’t want to do on your employer’s production server.” and Jello Biafra’s “A prank a day keeps the leash away.” Some days had more than one.

So I installed Movable Type, one of the first-gen blogging platforms, and began to type.

David Cassidy and the Stochastic Parrot

Working on the new book, I’ve ponied up for a newspapers.com subscription for research. In addition to the book research (1920s newspapers are a blast), a fun side benefit is access to a bunch of my old newspaper work.

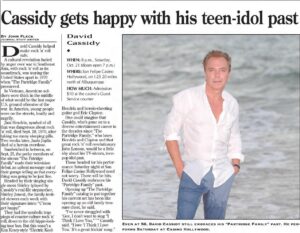

One of my first searches was for what I think of as the Fleckest thing I’ve ever written – the time I interviewed David Cassidy. Yeah, the Partridge Family guy, that guy.

some of the vast detritus of my newspaper carrier

It started as a joke.

On my morning commute, I’d seen a billboard announcing that Cassidy would be playing Sat., Oct. 21, 2006 at “San Felipe Casino Hollywood,” one of our Indian casinos. Our Friday entertainment section would do setup pieces for weekend shows, a delightful sad tired ritual where the publicist would set up a phone interview with the artist from some random tour stop the week before.

I wandered over to the arts desk and told Dan Mayfield that he should let me do the David Cassidy piece.

It was sort of a joke.

I was the science writer.

I had a reputation as the office policy wonk.

David Cassidy was an aging pop star.

But I have always taken my craft seriously, and also the Inkstain motto: “A prank a day keeps the leash away.”

Cassidy was a great sport in what must have been the approximately 5,782nd time he had to cheerfully reflect on his Partridge Family life.

The joy for me is rereading the rat-a-tat of my own voice, the way I used the Cassidy peg for a tight, sweeping little essay on ’70s art and pop culture. This is one my favorite paragraphs I’ve ever written. The setup was a paragraph introducing Shirley Jones and the Partridge Family’s peppy intro, “C’mon get happy!”, then somehow this spilled out.

They had the symbolic trappings of counter-culture rock ‘n’ roll, down to the old hippie-looking tour bus. But this wasn’t a Ken Kesey-style “Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” bus. Its colorful paint job carried the cheerful clean abstract lines of Piet Mondrian rather than the revolutionary stylings of Jasper Johns.

I still marvel at where stuff like that comes from.

In a widely read and lately even more widely quoted-without-reading-it-all 2021 paper, linguist Emily Bender and colleagues introduced the “stochastic parrot” to help us understand language models like ChatGPT, the “AI” thingie that all the cool kids are talking about. Language models ingest huge volumes of words written by humans and develop probabilistic models of what sort of words follow what other sorts of words.

They’re super interesting, and I’ve been spending a ton of time experimenting with ChatGPT, in part as a sort of “compare and contrast” to try to think about my own writer’s brain, which is a marvelous puzzle. Here’s Bender et al explaining the parrot metaphor:

A LM is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot.

You’re either on the bus or off the bus

The thing I puzzle about, that fills me with wonder, is how stuff like the Cassidy piece comes together in the chaos of my writer’s mind.

I had to start with Cassidy, and from somewhere – 11-year old me sitting in front of a TV with my 13-year-old sister, Lisa? – came the notion that the Partridge Family made rock and roll safe for suburban middle American us. I doubt I thought it up myself, all of my ideas are derivative, right? I’m no parrot, yes? An original thinker, yes?

David Cassidy helped make rock ‘n’ roll safe.

A cultural revolution fueled by anger over war in Southeast Asia, with rock ‘n’ roll as its soundtrack, was tearing the United States apart in 1970 when “The Partridge Family” premiered.

In Vietnam, American soldiers were thick in the middle of what would be the last major ground offensive of the war. In America, young people were on the streets, loudly and angrily.

Jimi Hendrix, symbol of all that was dangerous about rock ‘n’ roll, died Sept. 18, 1970 after taking too many sleeping pills. Two weeks later, Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose.

Sandwiched in between, on Sept. 25, the perky members of the sitcom “The Partridge Family” made their television debut, an upbeat message out of their garage telling us that everything was going to be just fine.

Rat-a-tat. “…perky… “…out of their garage….” I can still remember my delight at nailing down the timeline – Hendrix, Joplin, the Partridge Family. Rat-a-tat.

Off the bus?

Mondrian and Jasper Johns were just icing. Modrian was obvious – look at that bus! Jasper Johns rolled out of my own language model, the art I’d grown up around, the water I swam in as a juvenile fish, the obvious thing that comes after Mondrian when you’re looking for countercultural art.

Obvious, anyway, to a kid trained at LACMA.

Having been born in 1959, I always felt cheated that I was too young to appreciate “the Sixties”, but I played all the music as a college DJ after the fact, and I read the Electric Kool-Aid Acid test at a very impressionable moment in my development as a young writer – “You’re either on the bus or off the bus.” I had so very much wanted to be on the bus.

So all the raw materials were there. But how did my writer’s brain assemble them? I’ve no idea.

At this point, stuff like this is beyond the large language models.

While working on this piece, I prompted ChatGPT to output some words about the connection between David Cassidy and Jasper Johns. The resulting text was a story about how David Cassidy was a big fan and avid collector of the artist’s work.

It sounded great – that’s what LLM’s are good at, sounding great, a terrific parrot as parrots go – but seems not to be anchored in verifiable reality.

More deeply, to borrow from Bender et al, “without any reference to meaning” – somehow those life experiences, dropping acid and reading Kesey in the late 1970s in a desperate attempt to recapture the ’60s, standing in bemused fascination before a Jasper Johns flag at some big boy art museum show, scratchy Hendrix on the turntable at KWCW, sitting in the Fleck family TV room rapt in September 1970s – “c’mon get happy!” – assembled by my writer’s brain into my crazy wonderful David Cassidy piece, contained “reference to meaning.”

Where did I learn to be archly dismissive of Mondrian? Where did that come from?

Rat-a-tat.

Inkstain at 20

I eventually ported Inkstain to WordPress, and according to my installation’s database, when I hit “publish” this will be my 6,176th blog post here.

As I think I mentioned, I’d been crafting workable sentences for a living for 20 years by the time the blog launched, but this is where I learned to write.

Thanks for reading.