Flood control, navigation, irrigation, water storage, power: Hoover Dam, December 2011

Hey Lower Colorado River Basin. Can we talk?

I know, I know. It’s New Water Year’s Eve and it’s like a hundred something degrees and sunny and you wanna go water skiing on Lake Mead, all fat and happy with its 1,115.18 feet of surface elevation, glistening in that warm Nevada sunshine. Or you wanna grow some lettuce or something. I get that you have stuff to do. But really, we need to talk.

I just wanna point out that Lake Mead has less water in it today than it did when the last water year ended. I know, I know, it’s only a tiny bit less. But the thing is, we Upper Basin folks gave you a bunch of extra water again this year. How could Lake Mead be down?

I understand that rules are rules and a deal’s a deal. We agreed that when we have more water up here in Lake Powell than you do in Lake Mead, we’d send some of the extra your way. The law says we really only have to give you 8.23 million acre feet of water each year, but OK. Since Powell was looking a little flush, we sent you 9.463 million. That’s what the operating agreement says and, as I said, a deal’s a deal.

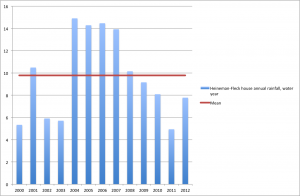

It’s just that, between drought and all the extra water we sent you, Powell’s down 3.6 million acre feet this year. That’s 1.2 million extra acre feet of water we sent your way this year, for chrissakes, while Lake Powell dropped 30 feet!

I hate to go all “big brother with his math” on you, but here’s the reality: Since 2000, we’ve sent you 6.3 million acre feet above and beyond the amount you can legally expect to get every year in the long term – the 8.23 million acre foot minimum release from Lake Powell each year under the Law of the River. During that time, when we’ve been giving you all that extra water, Lake Mead has dropped 80 feet.

What the fuck did you do with all that water? Did you just waste it on hookers and blow?