First, my apologies to Michael Campana, for whom my recent disquisition on hookers and blow on the Lower Colorado seems to have caused some inadvertent difficulties. I expect my Texas neighbors are the forgiving sort and will welcome you back. It would be unfortunate, given their recent difficulties with the whole running-out-of-water thing, if they were to cut themselves off from access to such a wise water policy sage.

Second, to my friends in the Lower Basin, I must apologize. As Emily Green wisely noted in the comments, who am I to judge whether hookers and blow are or are not a beneficial use of water?

Lake Mead water balance

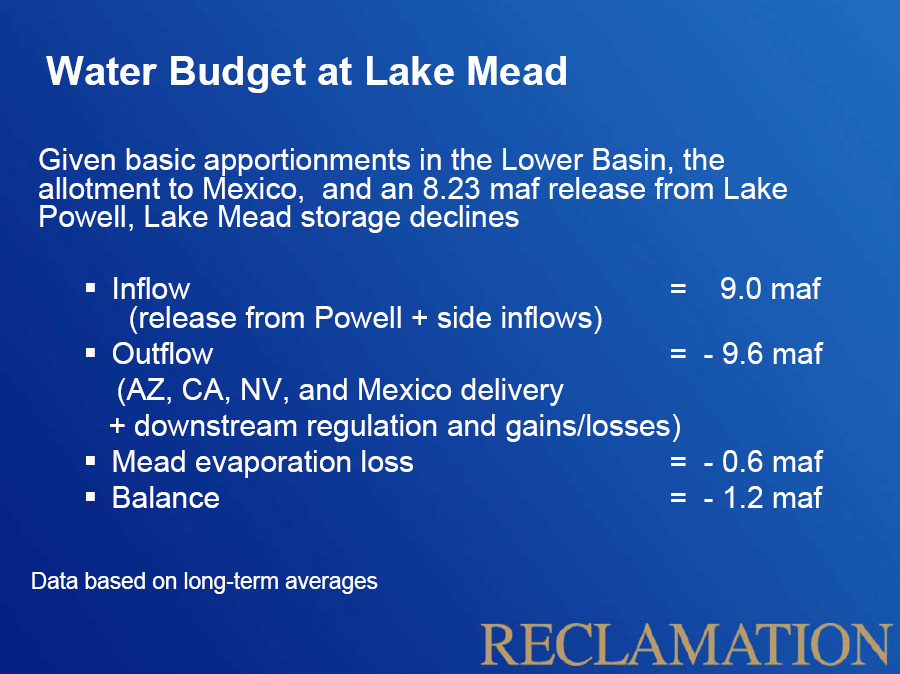

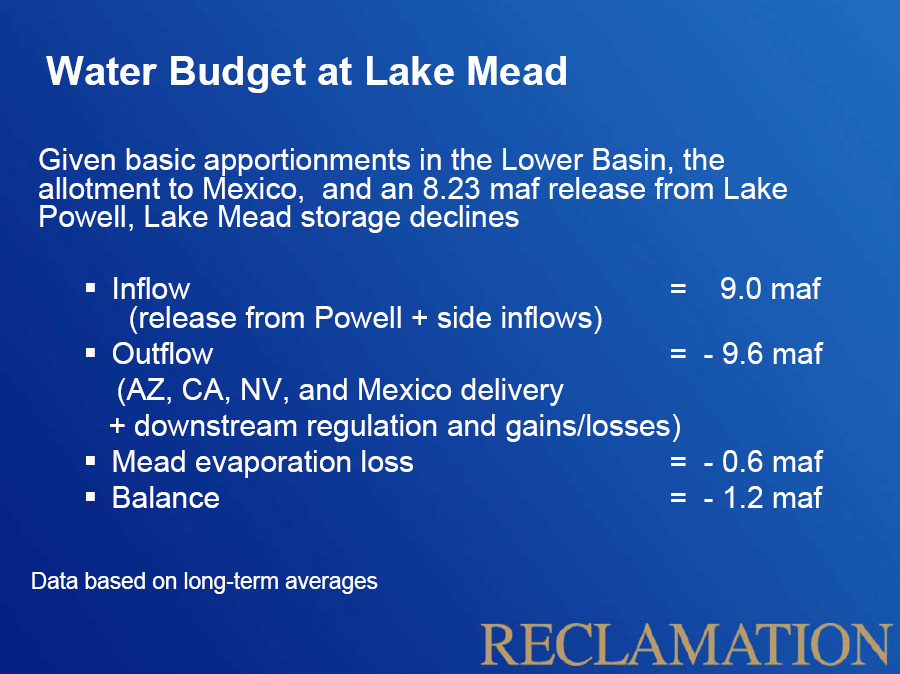

Also, I had this fancy spreadsheet I’ve been working on, with graphs and stuff, explaining the core problem – that, given its legal annual entitlement, without any “bonus water” resulting from either underuse or surplus supplies in the Colorado River’s Upper Basin, the Lower Basin is inevitably going to drain Lake Mead. But that’s wonky stuff that you’ve heard before (and here and here and here). There simply is no alternative, given the current approach to managing the river, to that reality. As the accompanying Bureau of Reclamation slide notes:

Given basic apportionments in the Lower Basin, the allotment to Mexico, and an 8.23 maf release from Lake Powell, Lake Mead storage declines

Recall that the long term supply and demand curves in the Colorado River Basin crossed some time in the late 1990s, and in the years since the states of the basin have been meeting their water needs by draining the reservoirs behind Glen Canyon and Hoover dams. Since 1999, the total water in storage behind the two big dams has decreased by 20.5 million acre feet (I think that’s 25.2 billion cubic meters, Andy).

More importantly for water management purposes, the total water in storage in Lake Mead, the savings bank to meet water needs in Nevada, Arizona and California, has declined by 11.5 million acre feet since 1999, despite the fact that in each and ever year the Upper Basin has met its legal requirement to deliver 8.23 million acre feet past Lee’s Ferry. Recall that under the Law of the River, we’ve sorta agreed to split this river at Lee’s Ferry, so it’s not entirely clear that we’re all in this together. As long as we Upper Basin people keep hitting that 8.23 maf target, y’all are on your own down there, I fear. Under the current situation, bonus water is a possibility in many years, but the Lower Basin can’t count on it forever.

I’ll roll out the fancy graphs next week, when I get the final water year numbers. But the wonky stuff never draws big web traffic, so, in the meantime, if nothing else, hookers and blow and the f-word sure got a lot of clicks!

.