Hoover Dam and the bathtub ring

Water is at the core of a compelling human drama. Or perhaps dramas (plural). Yet the core issues, where the drama lies, are maddeningly difficult to, if I may share a personal journalist neologism, “storyize”. Cynthia Barnett, my favorite water writer, explains in the Los Angeles Times:

But we can’t see dried-out aquifers the way we could see black Dust Bowl storms in the 1930s or water pollution in the early 1970s. So we still pump with abandon to do things like soak the turf grass that covers 63,240 square miles of the nation. We flush toilets with this same fresh, potable water, after treating it at great expense to meet government standards for drinking.

We fill the fridge with beef, the shopping bags with cotton T’s, the gas tank with corn-made ethanol — all with little inkling of how we’re draining to extinction the Ogallala aquifer that irrigates a quarter of the nation’s agricultural harvest.

So Cynthia, as we all inevitably do, makes the pilgrimage to Lake Mead, and points out the “bathtub ring”:

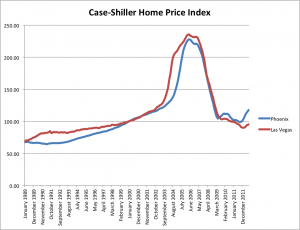

Lake Mead is different. It’s one of the few places in the United States where the illusion of water abundance is being exposed for what it is: a beautiful bubble doomed to pop, just like other great national illusions — the unending bull market, say, or upward-only housing prices.

For 12 years, the nation’s largest reservoir has dropped steadily to reveal a calcium-carbonate bathtub ring, evidence of human folly and nature’s frailty — the over-allocation of the Colorado River and the drought still battering so much of the United States.

The problem, she found on her visit to Hoover Dam, is the tales we tell ourselves. I struggled with this a couple of years ago on my own similar pilgrimage:

We are sufficiently buffered by affluence that almost no one I talked to today had any inkling of what was going on. Just another tourist Sunday on Hoover Dam. The best I got was from one the folks in this picture, who were on a Sunday drive at one of the Lake Mead overlooks. One of them, a Las Vegas resident, knew the lake was way low, and said the solution was simple – somebody needs to have the political courage to make them release more water from Lake Powell, upstream.

I decided against explaining the Colorado River Compact, and the complex reservoir equalization rules in the 2007 shortage sharing agreement, that upper basin states are using less than their share of the river anyway, that Powell is low too, that it’s not that easy. But ultimately, I guess that’s what I have to figure out how to explain.

Consider this a call for better storytelling. Cynthia’s LA Times piece is a good place to start.