Lake Mead shipwreck

LAKE MEAD – The Park Service has cut a raggedy new dirt road (“4×4 recommended”) north of Hemenway Harbor along Lake Mead’s receding shoreline so you can still get in to go fishing and do the beach thing.

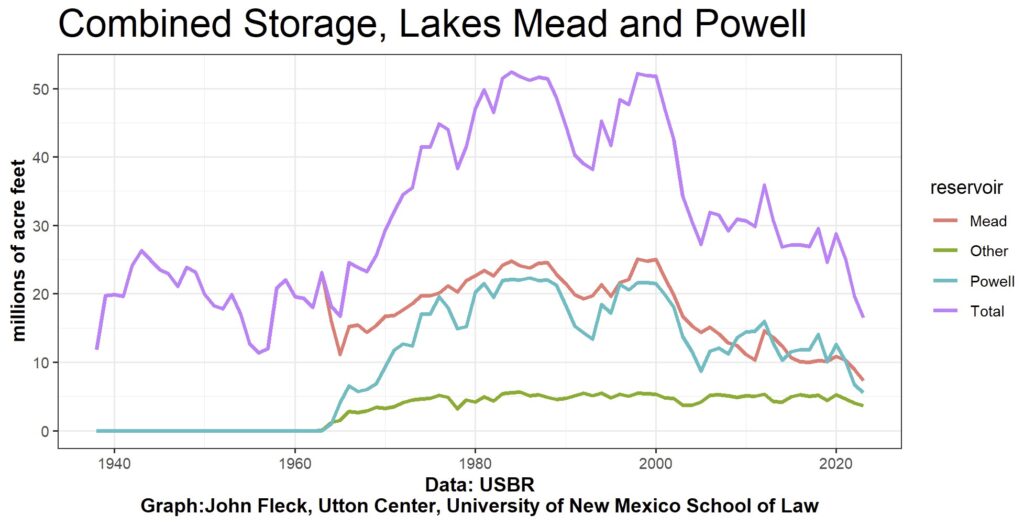

Mead was at elevation 1,043 and change as I rode it on my bike yesterday afternoon, with lunch and time on my hands to ponder the stakes. You could see the uppermost Las Vegas water pipe, exposed to the winter air, and the stranded intake from the World War II-era Basic Magnesium factory.

I passed three Lake Mead shipwrecks, the media icons of the great collapse, ruin porn of the Colorado River. I was happy, I guess, to finally bag the pictures for myself. I guess?

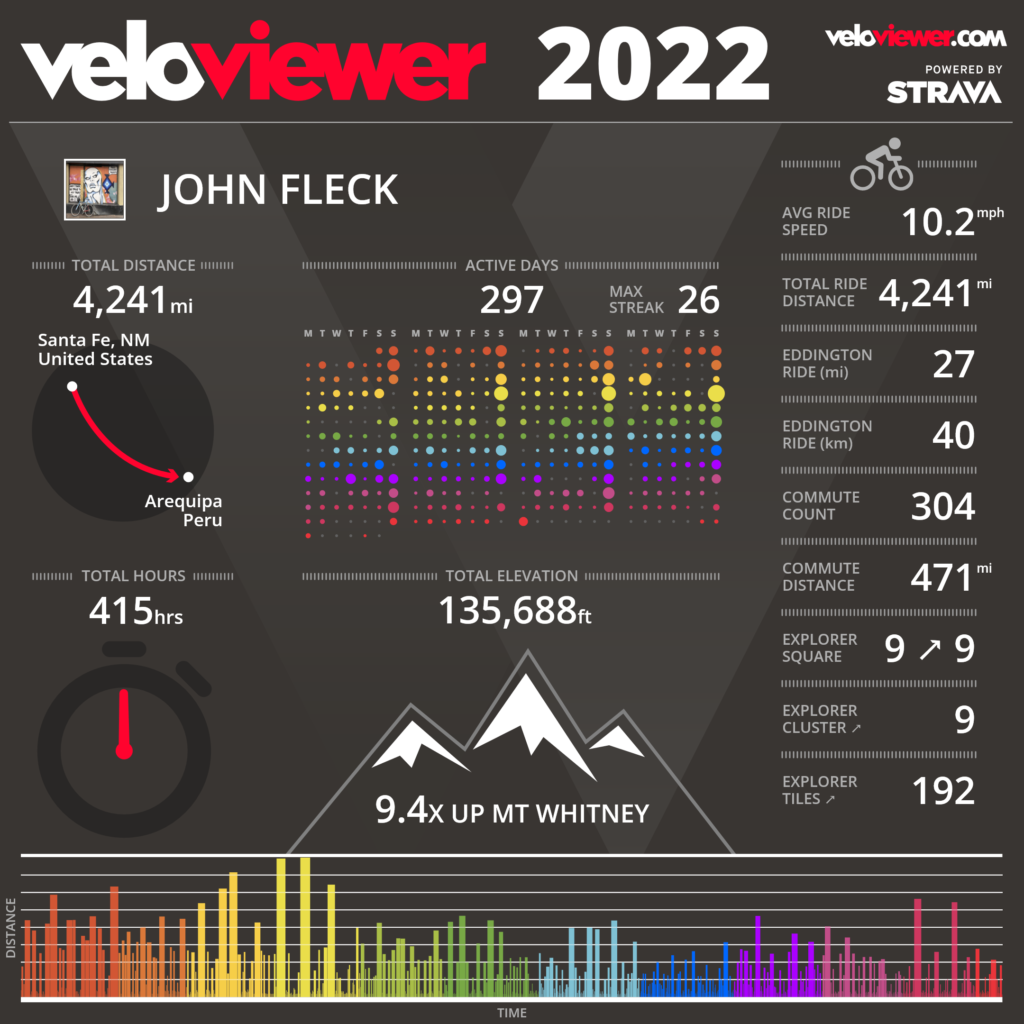

It was my annual pre-Colorado River Water Users Association Lake Mead visit – a bike ride along the reservoir, a trip to Hoover Dam, some quiet time in Boulder City before heading into the madhouse of Las Vegas and CRWUA and a Colorado River in crisis.

Managing in crisis mode

The challenge right now is a very practical one. We’ve no longer time the sort of vague generalizations I got when I turned to ChatGPT for help – “Implementing stricter water usage regulations and reducing water waste can help bring the supply and demand of the Colorado River into balance.” Great. Thanks. How we gonna do that?

The Colorado River brain trust has to write new rules, and it has to write them now, in a very specific way, with little time or room for error.

I have long had a dodge when reporters or my students or whoever asked me what I think we should do: It doesn’t matter what I think we should do, I would tell them. What matters, I would say, is what emerges from the seven states and the federal government, and increasingly the Tribes and others who who now, rightly, find themselves at the negotiating table(s).

Unfortunately, what has emerged from that process is shipwrecks emerging from Lake Mead.

So I’ve dropped the shield and begun thinking about how I would rewrite the rules, if anyone asked me. Come to think of it, the Federal Government has asked me, along with all the rest of you, via this Federal Register notice. You’ve got a week left before your assignment is due.

Basically, we need to do two things.

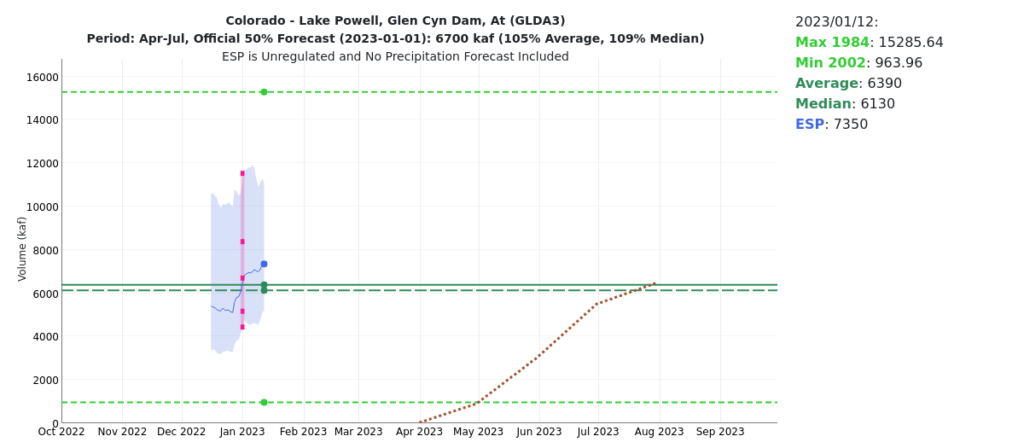

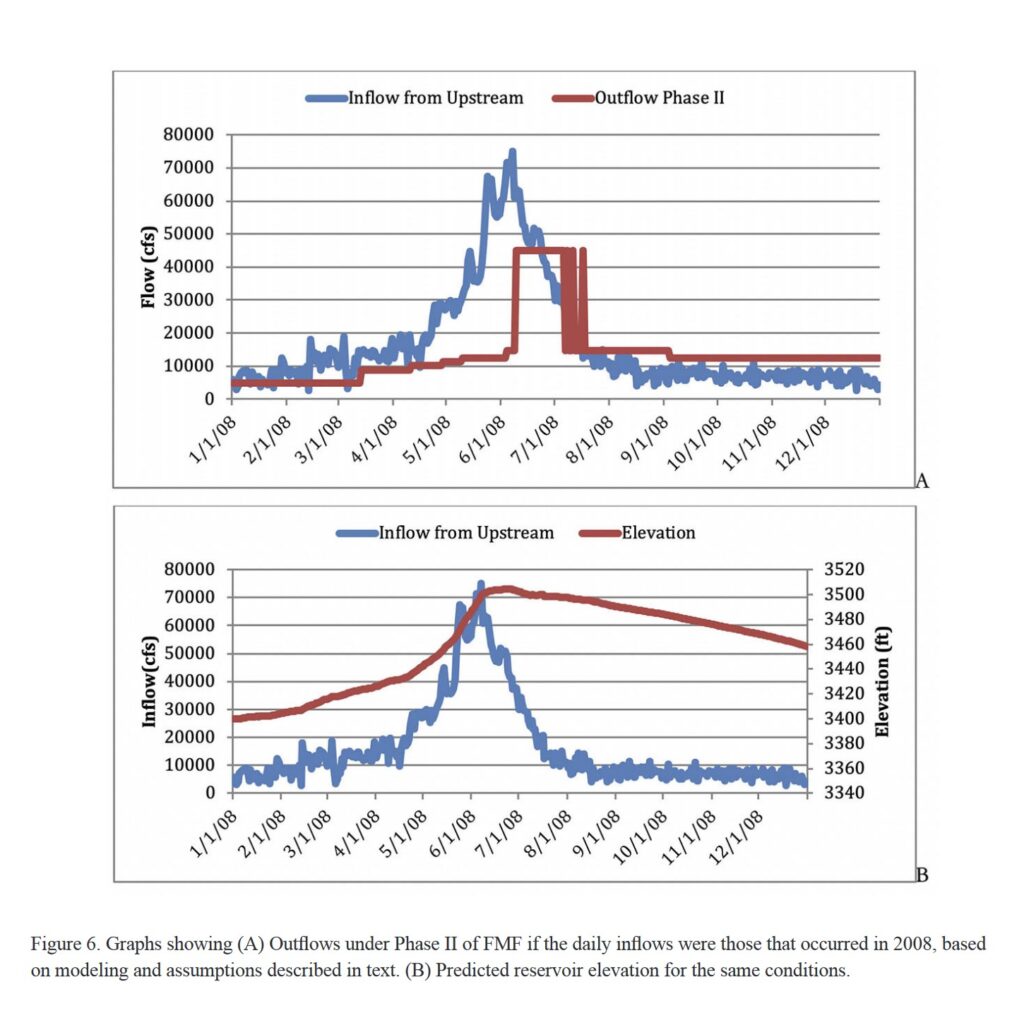

First, we need to rewrite the rules governing releases from Glen Canyon Dam to protect Lake Powell from reaching critically low levels that, by forcing the use of the dam’s lower outlet works, might threaten the structural integrity of the dam. We do this by setting a maximum release from Powell based on the current year inflow.

Second, we need rules to cut far more deeply into Lower Basin water use, like right now – far deeper than the rules we’ve got now. They’re just not sufficient. We have to include evaporation and system losses as part of each Lower Basin state’s allocation.

Saving Glen Canyon Dam

Section 6, Interim Guidelines

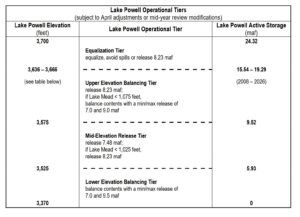

Section 6C and 6D of the 2007 Interim Guidelines is the critical first step.

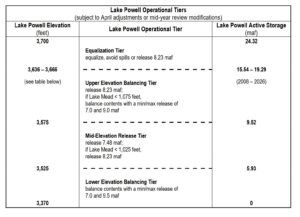

This is where the current rules lay out how much water is to be released each year from Glen Canyon Dam. Note the quaintly anachronistic “Lake Powell Active Storage” column on the right, with “dead pool” – zero active storage – at elevation 3,370.

If Reclamation decides it doesn’t trust the dam’s outlet works, which sit down there, then suddenly “active storage” doesn’t start until elevation 3,490, the level of the power plant intakes.

For now at least, 3,490 is the new dead pool.

That would mean that at elevation 3,525, rather than having 5.93 million acre feet of “active storage” – the amount of water above “dead pool” – we’ve really got less than 2 million acre feet of really actually usable, releasable water in Powell. The whole notion of “balancing” active storage in Mead and Powell, so central to the ’07 Guidelines, now has to look completely different.

When you get close to dead pool, you’ve got a “run of the river” system, which means that the only water that leaves a reservoir is the amount that comes in. Given that we’re apparently redefining that for Powell on the fly, the new versions of 6C and 6D somehow have to restrict releases from Powell to not much more than comes in. Basically starting now, and for the foreseeable future, until we can begin to refill Powell or drill some new tubes at the bottom that we trust.

A simple approach to the new rule here might be rewrite the release rules when you’re in the “Mid-Elevation Release Tier” (below 3,575) and the “Lower Elevation Release Tier” (below 3,525) to cap releases to inflow minus evaporation. That would set a sort ratchet that would prevent a further decline in Lake Powell below its current dangerously low levels.

You could start the year by capping Powell releases at the 24-month study’s “minimum probable” unregulated Powell inflow level, with the option of raising the release an April review based on the “most probable” unregulated inflow. Minus evaporation. You’d have to subtract evaporation from that.

Other than that, the 6C and 6D rules could stay the same.

Saving Lake Mead

As the modeling presented by Reclamation in its webinars two weeks ago shows, if you operate Powell the way I describe under low flow scenarios, you can crash Mead in a hurry. We need rules that are ready for that.

the Lower Basin “structural deficit”, reified

Taking evaporation and system losses off the top before we begin handing out water is a start. The “structural deficit” is real, it’s a result of not taking evaporation and system losses into account, and it’s written in shipwrecks emerging from the depths of Lake Mead.

Right now evaporation and system losses are in the ballpark of 1 million acre feet per year, but to be on the safe side, let’s set them at the 1.2 million acre foot per year level in the classic Reclamation “structural deficit” Powerpoint slide.

So the cuts in section 2D of the Interim Guidelines would have to be rewritten, with Arizona, Nevada, and California taking a proportional share of system losses right off the top.

You can do this some really complicated ways, based on the distance downstream of each user’s intake – so Imperial and Yuma would take a bigger system losses hit, and Las Vegas (pulling straight out of Lake Mead) would only suffer evaporative loss.

That seems like a recipe for scientized litigation, so my proposal is simple: Everyone shares this equally (sorry, Nevada friends).

That would leave us with a base allocation that looks something like this:

|

old allocation |

new allocation |

| CA |

4.4 |

3.696 |

| AZ |

2.8 |

2.352 |

| NV |

0.3 |

0.252 |

The cuts in the big ’07 Guidelines/DCP allocation tables would then be deducted from these numbers. So under this scenario, if we drop into the Mead elevation 1,040-1,045 tier, the total allocations would be:

|

1,040 – 1,045 |

| CA |

3.496 |

| AZ |

1.712 |

| NV |

0.225 |

| US Total |

5.433 |

Notably, this gets us to the 2 million acre of cuts Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton said we need in her testimony to Congress last summer.

Upper Basin

This obviously doesn’t touch the Upper Basin. The process Interior is using for this round of crisis management – a straight up revision to the ’07 Guidelines – doesn’t seem to offer a clear path to force the Upper Basin to come up with contributions of their own. For now, I’m OK with that. Since the ’07 Guidelines were signed, the Upper Basin has delivered more than 10 million acre feet of water above the required 8.25 million acre foot annual requirement. Despite that, the Lake Mead shipwrecks are emerging from the shallows. The key here is clearly to get Lower Basin overuse under control.

But I don’t think in the longer term the Upper Basin is off the hook. Reclamation’s modeling clearly shows a risk of the Upper Basin slipping below its 82.5×10 obligation if we have a few more bad years. We need a plan to deal with that. And it’s also a matter of fairness, in my view. We all have to contribute.

My scheme for Upper Basin contributions involves the next wet year – figuring out how to forego some of the Upper Basin storage we’ve got and get that water into Lake Powell instead. Suggestions for how to write that rule are welcomed – bonus if anyone can figure out how to fit that into the rewrite of the ’07 Guidelines currently underway.

Collaboration

I still believe in the power of the collaborative governance framework we’ve developed in the Colorado River Basin. As Assistant Secretary of Interior Tanya Trujillo told me when I was moderating her appearance at last summer’s Getches-Wilkinson Center conference, we’d be in a lot worse shape without it.

For what it’s worth, ChatGPT agrees: “Collaboration and cooperation among states and water users is crucial in finding solutions to the supply-demand imbalance on the Colorado River.”