Albuquerque’s “Barr Irrigation District”, circa July 2022

Barr Irrigation District

The home of the ill-fated “Barr Irrigation District” is not one of Albuquerque’s scenic destinations.

Perched on low sand hills between Albuquerque’s soft industrial underbelly and the city’s “Sunport” (our marketing appellation for what a lesser metropolis might call an “airport”), the old irrigation district land is today home to an interstate, a power plant, a couple petroleum tank farms, junkyards, and “Fresh and Clean Portable Restrooms”.

But in 1912, when the Barr Irrigation District first glimmered in the eyes of Albuquerque boosters, it was going to “transform the central Rio Grande valley into a veritable garden spot.” A thousand acres of crops, “marketed here for home consumption and shipment” would be “the best thing for Albuquerque’s growth and prosperity” – “a rich agricultural district with this city as the center and distributing point”. (Albuquerque Journal, Jan. 13, 1912)

All that was needed was water, and H.J. Buell, an “irrigation expert” down from Denver, had the answer – “a pumping system operated by electric power”!

“Water in abundance is found at comparatively shallow depth,” the Albuquerque Journal explained in January 1912. The Journal suggested a great “free water” racket to support the enterprise: farmers could sell their rights to surface water flowing through ditches “for a substantial sum” and use the money to build more pumps and irrigate more land. (Research note: This is one of the earliest references I’ve found to sale of water rights in the valley as an economic scheme.)

As near as we can tell, a few farmers did, in fact, sign up with Buell and pump water up to the sandhills. But as the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District made farming in the valley below more attractive by draining swampland and re-jiggering the irrigation works, the project faltered. In the ensuing years, the low sandhill area was institionally reconfigured as the ~800-ish acre “Barr Irrigation District”, the the scheme shifted from pumping groundwater to making the area an extension of the Conservancy District’s existing valley floor irrigation system, pumping ditch water instead.

Like much about the valley’s irrigation schemes, success hinged on find a source of “other people’s money” to pay for it, and when efforts at procuring federal cash failed in the 1930s, the Barr Irrigation District faded from view.

Themes from the book

Two holiday weekend diversions took me into this part of the valley south of Albuquerque – me on a Canada Day weekend bike ride with Scot, and Bob in the archives after I returned from the ride and peppered him with questions. (Having a Regents Professor with mad skills as my “research assistant” for the new book is a pretty sweet perk of the current project. Plus #GeographyByBike – Scot’s importance as a research assistant in this part of the project is crucial.)

Down the hill from the never-realized Barr Irrigation District is the Barr Canal. It’s one of those Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District ditches that has a distinctly “modern” feel – the sharp straight lines of 1920s engineering superimposed over the meanders that went before.

When I say this part of our valley might not qualify as one of Albuquerque’s scenic destinations, I say so with tongue slightly askew. It’s actually an aesthetically fascinating area, a strange mix of Charles Sheeler-esque industrial majesty, movie-set post-apocalyptic junk, and farm. My crazy GPS bike riding map games suggested this was an under-explored piece of Albuquerque, a shortcoming that, with Scot’s help, I’m working to correct.

This part of the junkyard included piles of junked dumpsters. It looked like the graffiti was applied before the container’s arrival.

Scot and I this weekend rode up the Barr from the south, where it cuts through the Albuquerque Metal Recycling yards. ‘Round the back, the Barr splits the main recycling yard from its more post-apocalyptic back acres, the place where the junk yard seems to junk its junk.

It includes trashed trucks from UPS and Federal Express, and (my favorite part) an area devoted to junked dumpsters.

Mostly it was just a bike ride, but when we’re riding the valley floor, there really is no such thing as “just a bike ride”. I’m puzzling out the geography of the valley floor – why some places are homes and twisty streets, some areas were left as big farm fields, and some places got stuck with the city’s junkyards.

In his fascinating new book Tributary Voices, Paul Formisano takes on the stories we’ve been telling ourselves about the colonial watering of the west:

Striving to return to the garden once lost through the Fall, nineteenth-century beliefs about the arid West dictated man’s divine right to drastically alter the region for the onward march of progress and civilization.

Standing alongside Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier myth, the garden myth spilled awkwardly into 20th century Albuquerque in places like the Barr Irrigation District.

I don’t know that the Barr and this stretch of Albuquerque’s southeast valley will make it into the new book Bob and I are writing (Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, available several years from now, once we finish writing it, at a fine bookseller near you). We have too many stories already. But it illustrates a bunch of our central themes.

- The myths of agriculture: Albuquerque and the surrounding Rio Grande Valley may never have had the dreamy agricultural past to which the boosters claimed they wanted to return, and to which the modern water policy boosters still often mythologize. But true or not, the vision shaped the city we became.

- The role of institutions: In addition to the Barr Irrigation District, this part of the valley was home to the brief life of something called the “South Albuquerque Drainage District”. Formed in 1920, the District never seems to have gotten off the ground, and was subsumed into the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District when it was formed in the years that followed. In developing our water management institutions, scale mattered.

- The greening (junkyarding?) of the valley floor: The once-swampy lowlands of the valley floor were changed forever when the Conservancy District’s draglines sliced through in the 1930s, digging the low-lying ditches we call “drains” that were the district’s most important accomplishment.

The greening of the valley floor

Junkyards and farms along the Barr Canal, Albuquerque, 2022

This stretch of the Barr is my new favorite Albuquerque ditchbank ride (sorry, Los Griegos!).

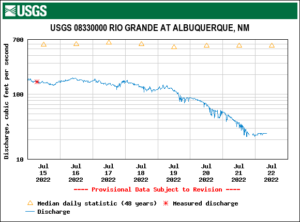

Up from Rossmoor Road, passage through the junkyard and into the old Schwartzman farm is weird. Smashed cars being ground up for scrap to right of us, scrapped UPS trucks to the left of us, the Barr in between running full and happy right now, and up ahead, one of the last big commercial alfalfa fields in the county being cut.

On lands that seem not to have been farmed or even settled during Albuquerque’s colonial period, the farm and the junkyard sit on land that was an old stockyard and meat processing plant run until the early 1980s by the Schwartzman family. While the sandy soil and lack of drainage may have made this part of the valley relatively less attractive than Astrisco and surrounding villages across the river, the railyards, and then drainage, made the area ideal for Albuquerque’s industrial underbelly.

The Schwartzman land has been slowly but surely carved up in recent decades, but when Scot and I left the awkward confines of the junkyards onto an open ditchbank flanked by fields, a farmer was still on the land, spending their Canada Day holiday weekend methodically cutting hay.