Another episode in my effort to explore the meaning of “drought” by way of example.

Tramway wetland, November 2012

Up on Albuquerque’s north side is a spot the birders call the “Tramway wetland”*. It’s the spot where the main flood control channel for much of Albuquerque slows before entering the Rio Grande. The local flood control authority has designed a wide shallows to catch the water and allow grody gunk to settle out, to reduce the amount of urban runoff contamination entering the river. It usually smells bad and looks even worse, but the birds, especially migrating shorebirds, love it because it’s one of the few large areas of shallow water in a stretch of river that once would have had much shallow water, before humans used dams and levees to break it of its meandering ways.

More than once I have taken my sandwich and binoculars to the Tramway wetland, which is not far from my office, at lunch. Smell notwithstanding, the birding is great. I’ve seen 50 species there, and the eBird reports for the site list 191 species.

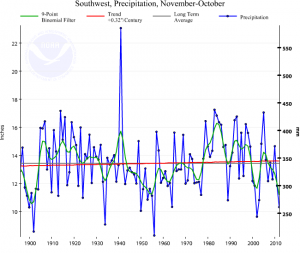

I was out on Friday looking for a rare dunlin that several birders had spotted, and was amazed at how little water there was in the wetland. Just a few pools in the deepest spots, far less than usual. There are two things likely going on here. The first is “drought” by the conventional definition: not a whole lot of rain. Since Sept. 1, we’ve had just 0.55 inches (1.4 cm) of rain at the rain gauge at the airport. Average for this stretch is 2.58 inches (6.55 cm). So there’s less rain flowing down the flood control system and out into the wetland.

The second effect is distinctly anthropogenic.

In addition to rain, the flood control system gets some water when Albuquerque’s municipal water agency starts up one of its big groundwater pumps. They flush an initial pulse of water into the flood control system, which makes its way down to the wetland. Albuquerque has shifted some of its demand to surface water, using a dam along the Rio Grande to divert water for municipal use. This seems to mean less pump flushing, and therefore less “wasted” water flowing into the Tramway wetland.

Here, I think, there is drought.

There were still a dozen sandhill cranes, drought or not, poking around in the barely-wetland, plus a great blue heron, some odds and ends of ducks that I really felt sorry for poking around in the mudholes that are left. And maybe the dunlin. Couldn’t be sure as it took flight, so I didn’t add it to my life list.

* The bridge in the picture is actually Fourth Street NW, or maybe Second Street NW (a confusing intersection), which turns into Roy Road, which eventually turns into the road we call Tramway. Don’t ask me why it’s not therefore the “Fourth Street wetland”. I just do as I’m told.