Nearly every time I ride past this place, I take a picture and try to remember to write about bananas in Albuquerque history. I have quite a few pictures. Today is the day I remembered.

It’s at First and Roma downtown, backing up on the railroad tracks, around the corner from the new at-grade railroad crossing, where I always detour my bike rides in the hope of being stopped by a train. I love being stopped by trains on bike rides.

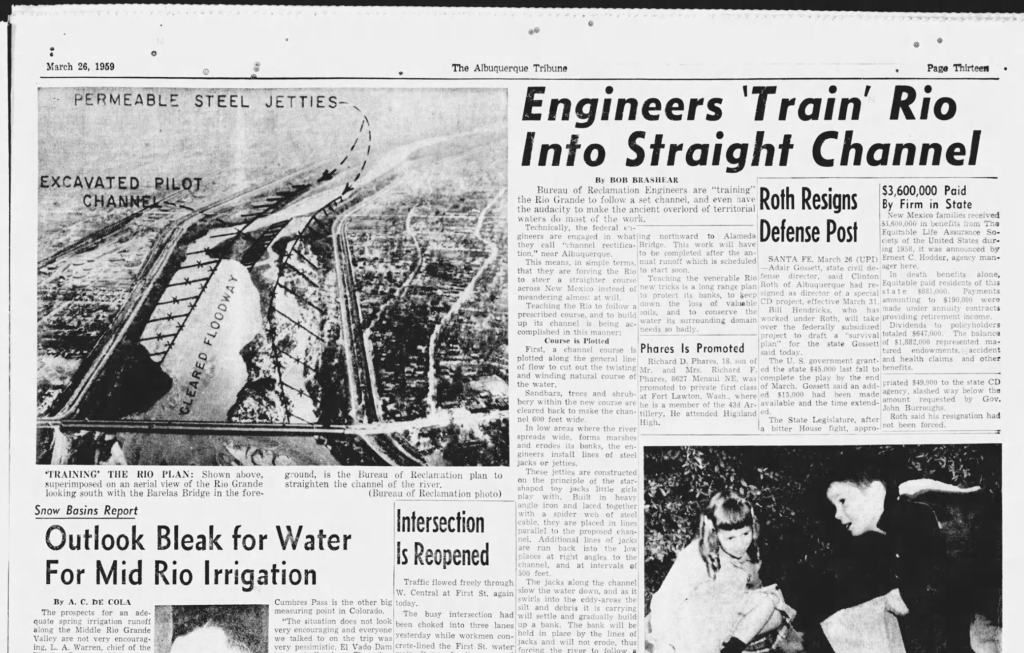

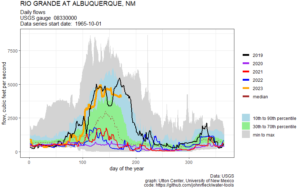

The railroad is central to the book Bob Berrens and I are writing. The book’s name plate says it’s about the history of Albuquerque’s relationship with the Rio Grande, but you can’t tell this story without understanding the affect of the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway in 1880. In the push<->pull of river and growing city, the railroad provided a huge “oomph” on the “growing city” side of things.

New Mexico Produce began operations in the 1930s in a warehouse building backing up to the railroad tracks. But it was not the first. In 1931, J.L. Hutchison built what the Albuquerque Journal described as “one of the finest and most modern fruit and vegetable warehouses and cold storage plants in the southwest.”

Banana Rooms

Hutchison’s new plant, a couple of blocks to the south, also backed up onto the tracks. It had, per the Journal, “six banana rooms with a capacity for more than 1,000 bunches of bananas.”

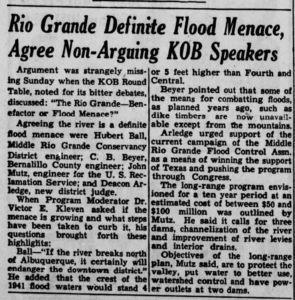

1931 is an important year in the history of Albuquerque’s relationship with the Rio Grande. The Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, created in the 1920s to bring flood control, drainage, and irrigation to the valley, was digging its first drains and throwing up its first levees. Here’s the Albuquerque Journal describing the connection between the creation of the district and Hutchison’s investment in cold storage and banana rooms.

The building is ideally situated, having railroad trackage on two sides. It was constructed with the idea of being in a position to take care of tremendous shipping business, which Mr. Hutchison declares is certain to follow the completion of the conservancy project.

Here’s the thing. Hutchison was not building for an export market. He was not setting up a business to help valley farmers export their crops. We don’t grow bananas here. He was building for the needs of a growing city for imported produce. The Hutchisons, J.L. and his wife (sorry, I don’t know her name, she’s just Mrs. Hutchison in the accounts of the day) were betting on a growing city, not on local agriculture.

Indeed, by the early 1930s the old Mann and Blueher truck gardens that sprang up to feed a growing population in the decades after the railroad’s arrival had largely been driven out of business by advances in refrigeration and the imported foods made possible by the new technologies. Local folks wanted fancy food! Bananas!

Hutchison graciously offered use of space next to his warehouse for the city to set up a marketing center for local producers. It appears nothing came of it.

Wholesale bananas today

If this were an actual book chapter and not just a blog post (which it probably needs to be, y’all see first sketches here) I’d run down the story of New Mexico’s 21st century banana warehouses. Not sure where they sit before they sit at the back of the produce section at Kroger’s. The best I’ve got right now as a closer is that the old New Mexico Produce building was converted in the 1980s to office space, and Hutchison’s old banana rooms, as near as I can tell, have been replaced by the parking garage for the Albuquerque Convention Center.

We don’t get much freight on the old rail lines. There’s an auto unloading complex south of town, but I never see freight trains this far north, only the Amtrak Southwest Chief eastbound to Chicago and westbound to LA, and the daily Rail Runner commuter trains to Santa Fe in the north and Belen in the south.

Our relationship with the railroad has changed. The city it wrought has too.