A 2022-23 forecast fraught with risk for the Colorado River Basin

By Eric Kuhn, John Fleck, and Jack Schmidt

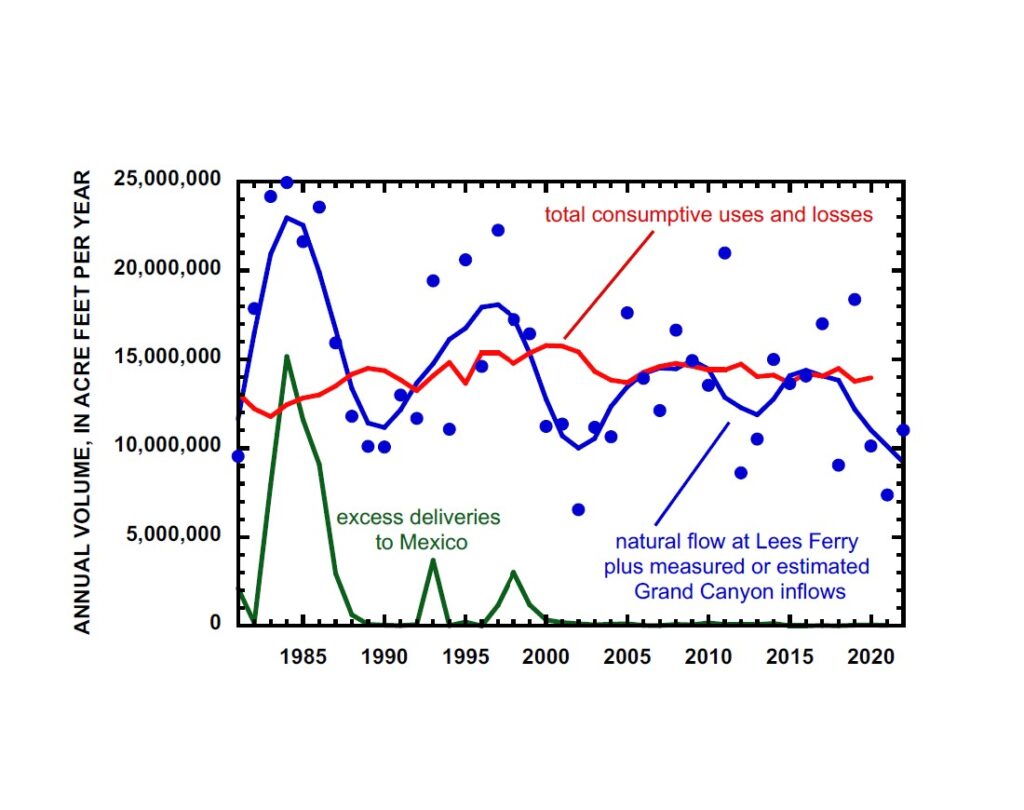

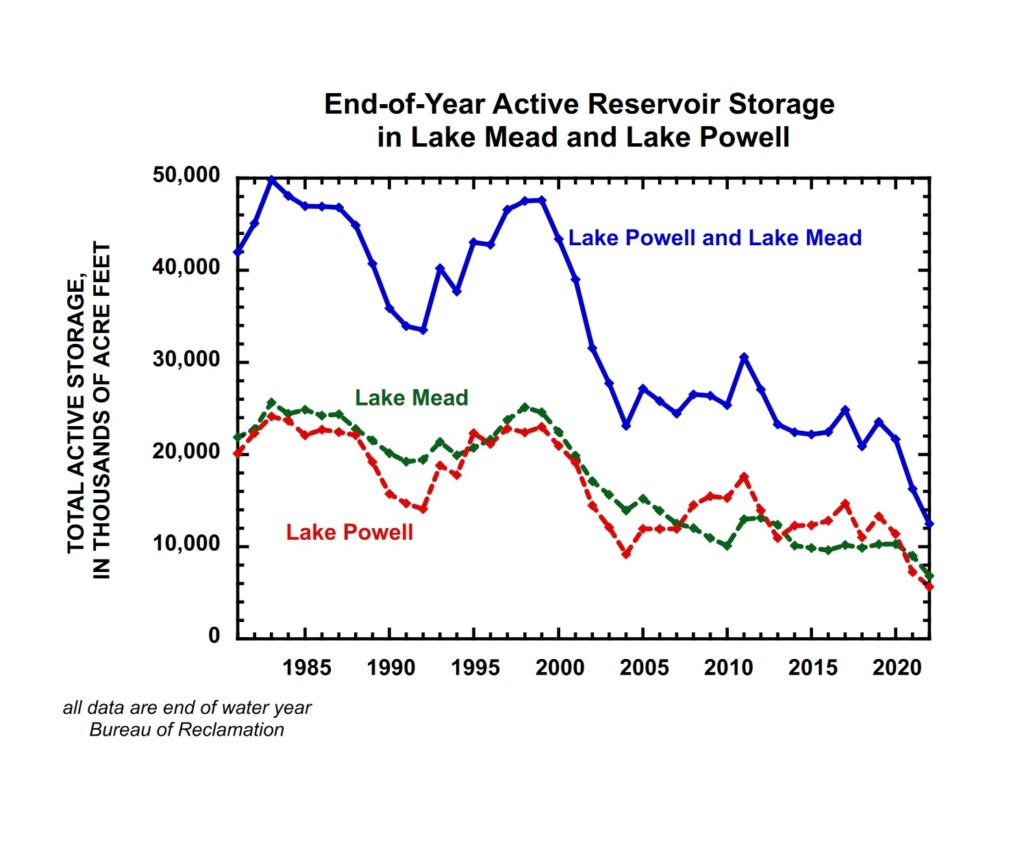

With most forecasts pointing toward another below-average winter of precipitation in the Rocky Mountains in 2022/2023 and with total basin-wide reservoir storage now less than 20 maf (less than 17 months of supply at the rate water has been consumed in the basin since 2000), it is time for the federal government to announce immediate, major reductions in Lake Powell releases for the coming water year (October 1, 2022, to September 30, 2023).

The importance of this leadership by Interior is pressing, because discussions among the basin states to cut their 2023 consumptive uses are at a stalemate and the Bureau of Reclamation is struggling to move the negotiation process along. An announcement by Interior, made no later than the 2022 Colorado River Water Users meeting in December, should set the annual release from Lake Powell for Water Year (WY) 2023 at approximately 5.5 million acre-feet (maf), 20% less than the 7.0 maf releases in water year 2022 and more than 30% less than the long-term release of 8.23 maf. Reductions in monthly releases to accomplish this objective ought to begin in January 2023.

In a news release Thursday, and in conversations at the Water Education Foundation’s Colorado River symposium this week in Santa Fe, officials with the Department of Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation suggested this option is already on the table. And Lower Basin water managers, doing the math for themselves, are already bracing for the possibility. A formal announcement, soon, would thus come as no surprise.

With last year’s decision to only release 7.0 million acre-feet in WY2022 (the water year that ends on September 30), the Secretary of the Interior has already determined that she can and will take actions to protect power generation and the structural integrity of Glen Canyon Dam. We believe it is now time to take bold action and further reduce Lake Powell releases for the following reasons:

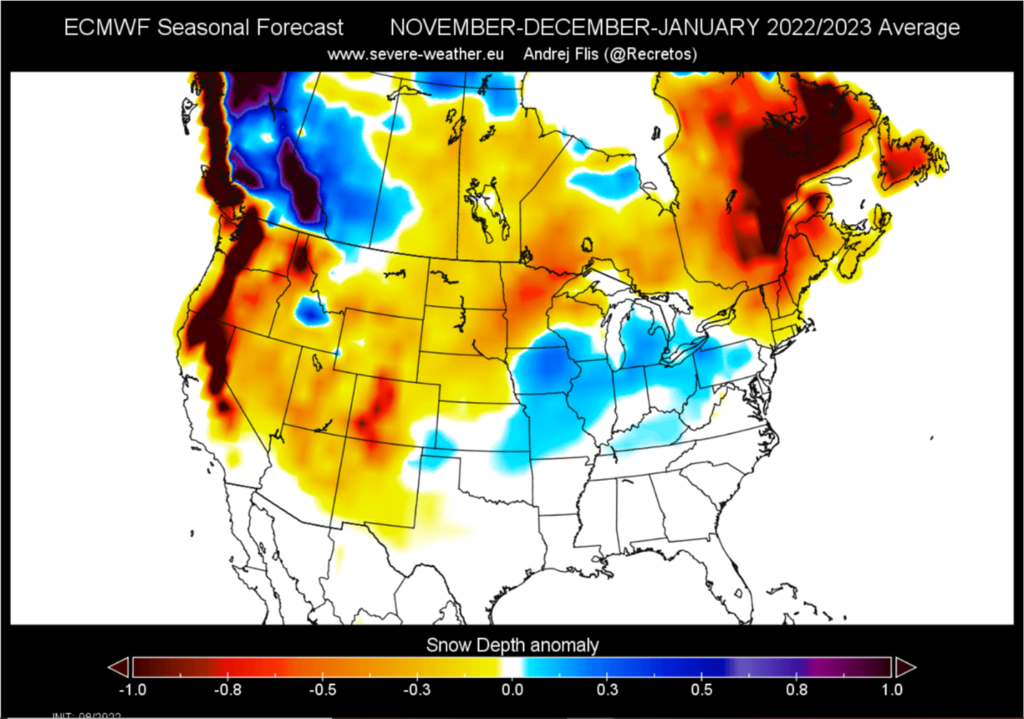

First – The winter forecast justifies an immediate reduction in releases. It is now clear that we’re headed for a La Nina three-peat at least through most of the winter. While there is still a lot of uncertainty, too many forecasts are pointing to a warm, dry winter for most of the Colorado River’s watershed, especially the Rocky Mountains. This warm and dry winter outlook means it’s time to focus on the likelihood that inflows to Powell will probably be similar to Reclamation’s present minimum probable forecast made in its 24-month study.

Second – The projections of the current 24-month study’s minimum probable forecast justify a drastic reduction in releases. Given the dry and warm winter forecasts, basing 2023 reservoir operations on the minimum probable forecast should be considered responsible water-supply management. Based on the latest projections made by Reclamation, storage in Lake Powell would drop to elevation 3469’, only ~2.7 maf of storage above the dead pool, and well below the 3490’ elevation below which hydroelectricity cannot be generated. Keeping the storage level above 3525 ft may not be possible, but an infusion of 2 maf of storage into Lake Powell through a combination of Drought Operations (DROA) deliveries from Flaming Gorge reservoir and reduced releases to Lake Mead would increase the probability of maintaining Lake Powell slightly above 3510 ft, a 20-ft (1 maf) cushion above minimum power pool elevation. Recognizing recent cautions from Jim Prairie (the UC Region’s lead modeler) that there may only be two years of DROA releases left in Flaming Gorge, a 500,000 af delivery combined with a 1.5-maf reduction in releases from Glen Canyon Dam would be a wise strategy that would leave Reclamation with the flexibility to make one more Flaming Gorge DROA delivery in 2024, if necessary.

Third – A 5.5-maf release would create clear markers to evaluate the impacts of the additional Lower Basin cuts on storage in Lake Mead and show what is necessary to preserve power generation at both Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams. Such an action would show the urgent need for additional system cuts to preserve both Lake Mead and total system storage. A reduction in the annual release by 1.5 maf would drive Lake Mead below elevation 1000 ft, but releases of only 5.5 maf would also be likely to keep Lake Powell above minimum power pool. At the end of WY2023, Lake Mead active storage would fall to 3.7 maf (~elevation 988 ft). Assuming a resumption of 7 maf-Glen Canyon Dam releases in WY2024, Lake Mead storage would drop to elevation ~965-970 ft in July 2024, close to its minimum power elevation of 950’. Under this scenario, both reservoirs would have only about a 20 ft cushion over minimum power pool elevation, but power generation at both dams would be preserved, albeit at a minimal level.

There are obvious tradeoffs between the reduction of Lake Powell releases to our suggested 5.5 maf and the imposition of additional reductions in Lower Basin consumptive uses. Reduction of Lake Powell releases to 6.0 million acre-feet in WY2023 would be the largest release that ought to be considered for the coming year, because such a release would only increase storage about 20 ft. Reducing releases to 5.5 maf or even 5 maf would be much wiser, but even these radical policies may only be enough to “tread water.” Recovering system storage is likely to take several more years of reduced releases from Lake Powell that might include additional years when annual releases are as low as 5 maf.

Fourth – If the forecast of a dry winter proves to be in error and more precipitation comes in late winter 2023, Reclamation can increase the annual release during the spring. Reclamation has the flexibility to increase annual releases back to 7.0 maf/year (or more under the possible, but unlikely, event of a big year). Ideally, if the Lower Basin has a plan in place to cut an additional 1.5-2.0 maf of its uses, the benefits of such an increase in Powell releases later in the water year could also be redirected to recovering storage in Lake Mead.

Fifth – A 5.5-maf release in WY2023 could leave the Upper Basin with a future compact deficit that would force resolution of the long-standing dispute over the Upper Basin’s 1944 Treaty obligation to Mexico. The ten-year flow at Lee Ferry for 2013-2022 will be about 85.5 maf, but under our proposed scenario of a 5.5 maf release in WY2023 and a continuation of the Millennium Drought, the ten-year total release would be less than 82.5 maf by 2025 or 2026. Further, as the 9-maf years from 2015-19 fade into the past, the running ten-year tally could stay well below 82.5 maf through the end of the decade.

Denver Water CEO Jim Lochhead has labeled this 82.5 maf metric as the basin’s first hydrologic “compact tripwire.” This observation is based on the Lower Division States’ view that under the 1922 Compact, the Upper Division States have an annual obligation to contribute 50% of the 1944 Treaty delivery to Mexico every year (normally 750,000 af, but a little less when Mexico takes a shortage) plus the 75 maf non-depletion obligation. The Upper Division States, of course, disagree, taking the position that the 750,000 af release for Mexico is a “luxury”, not a requirement under the 1922 Compact. Their view is that their Lee Ferry obligation is no more than 75 maf every ten years.

The Upper Division States’ position, however, puts their post-Compact uses at considerable risk! If the basins are unable to reach a compromise and turn to litigation instead and the Supreme Court rules in favor of Arizona, Nevada, and California or even finds a middle ground, it’s quite likely that the Upper Division States could end up owing a lot of water or money or both. The Upper Division states would be wise to consider resolving their Mexican Treaty obligation as a part of the post-2026 guidelines negotiations. Having an effective Upper Basin demand management program (or functional alternative) in place will almost certainly be a part of any negotiated settlement.

Summary If the WY 2023 runoff turns out to be below average, as many forecasts now suggest, maintaining Lake Powell storage elevation above minimum power pool with a reasonable cushion will require a combination of (1) another DROA release from Flaming Gorge Reservoir and (2) a significant reduction of the WY 2023 Lake Powell release to well below 7 maf. At this point, using the most probable 24-month forecast which uses an optimistically wet (1991-2020) hydrologic baseline and totally ignores the available winter forecasts, simply obfuscates reality, and creates obstacles to finding the needed cuts. Using the minimum probable forecast to set the 2023 annual release sooner than later would add both clarity and urgency to the stalled task at hand – finding the necessary additional cuts needed to stabilize and recover the system. Using the minimum probable forecast is a “no regrets approach.” If the forecast improves, an upward adjustment of annual releases is an easy and welcome fix. The opposite, a downward adjustment made in spring 2023, would create more havoc.

There are associated issues that Reclamation ought to begin to consider immediately. What would be the impact to the Grand Canyon ecosystem of a 5.5-maf annual release? How should monthly flows be distributed under such a low annual release? How should the present invasion of smallmouth bass in Grand Canyon be managed under very low annual releases? What might be the impact on commercial river running in Grand Canyon in 2023? How should the ever-increasing temperatures of Powell releases be managed? These are all questions that need to be addressed in fall 2022 so that our recommendations can be implemented in January 2023.

We’ve suggested the 5.5 maf figure based on the September 24-month study. By November or December, the minimum probable forecast may dictate a different release number.

Whatever that number is, Reclamation should consider letting the basin know as soon as reasonably possible.

- Jack Schmidt is Janet Quinney Lawson Chair in Colorado River Studies, Center for Colorado River Studies, Watershed Sciences Department, Utah State University

- John Fleck is Writer in Residence at the Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico School of Law; Professor of Practice in Water Policy and Governance in UNM’s Department of Economics; and former director of UNM’s Water Resources Program.

- Eric Kuhn is retired general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District based in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and spent 37 years on the Engineering Committee of the Upper Colorado River Commission. Kuhn is the co-author, with Fleck, of the book Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River.