It is a strange reality of our modern world that, in the face of a truly remarkable drought here in the Middle Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, I was able to pour imported Colorado River water on purely ornamental plants in my garden yesterday morning. I’m thrifty with the water – a modest drip directly to the roots of a handful of shrubs in the backyard. But compared to the farmers I’ve been hanging out with of late, this is non-essential water.

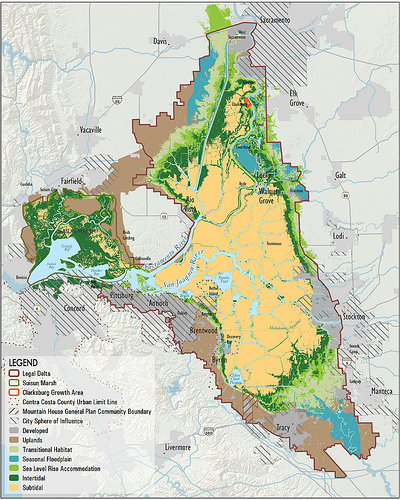

The water comes from the headwaters of the San Juan River in southern Colorado, diverted via three small dams to the Azotea tunnel, into Heron, then El Vado and Abiquiu reservoirs, then down to a diversion dam on Albuquerque’s north side. From there, it is treated and mixed with fossil groundwater pumped from beneath Albuquerque so it can be applied to our mountain mahogany and New Mexico olive and a lovel piñon that once served duty as a Christmas tree before transplantation into the backyard.

Here is why I felt compelled to haul my trickling hose from plant to plant yesterday morning:

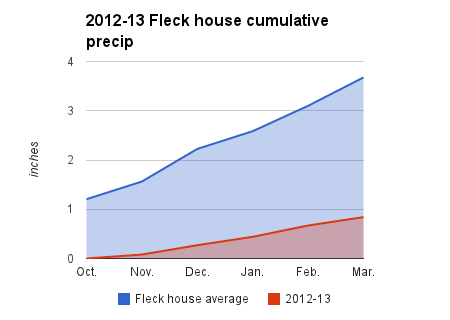

The total for the first six months of the 2012-13 water year at my house has been 0.84 inches (2.1 cm) of precipitation. That’s less than half of the previous dry year record in my 14 years of data collection, and less than a quarter the long term average of PRISM data for the neighborhood.