Heineman-Fleck House common birds: percentage of lists with five common bird types

In the last five years, I’ve somewhat haphazardly accumulated what’s turning into a pretty good time series of data on the ecology of my backyard. Or, more specifically, the birds therein.

Since 2008, when I caught the eBird bug, I’ve submitted 483 lists for the yard. Number 484, collected this evening, is a puzzle.

Sometimes a bird list is as quick as 5 minutes with a morning cup of coffee, sitting bundled on the back porch. When the weather’s warmer (data bias!), the lists get longer. In the warm half of the year, Lissa and I will often sit in the back until there’s too little sun for her to see her book and me my birds. I’ve gotten a great feel for what to expect, and what’s unusual.

Even if I’m only out for a few minutes, I’m reasonably certain to get house sparrows, house finches, lesser goldfinches and our two most common doves (white-winged and mourning). In recent years, add lesser goldfinches, since I began feeding them. In the winter, add dark-eyed juncos to that list. In summer, add black-throated hummingbirds. The pigeons that live at the market down there street almost always show up pretty quickly.

There’s a second category of birds that usually show up if I’m out long enough – robins are in that category. Recently, a pair of ladder-backed woodpeckers have taken up residence in a neighbor’s yard. These birds are around, just in lesser numbers, so probability requires more time before they pass through our yard.

Then there’s the long tail of the statistical distribution, birds I only see once or a few times each year, the odd yellow-bellied sapsucker and brown creeper in my yard lists. The long tail is fun.

Tonight, two long tail birds showed up – birds that are relatively common locally, but uncommon as visitors to the strangely altered ecosystem that is a suburban neighborhood.

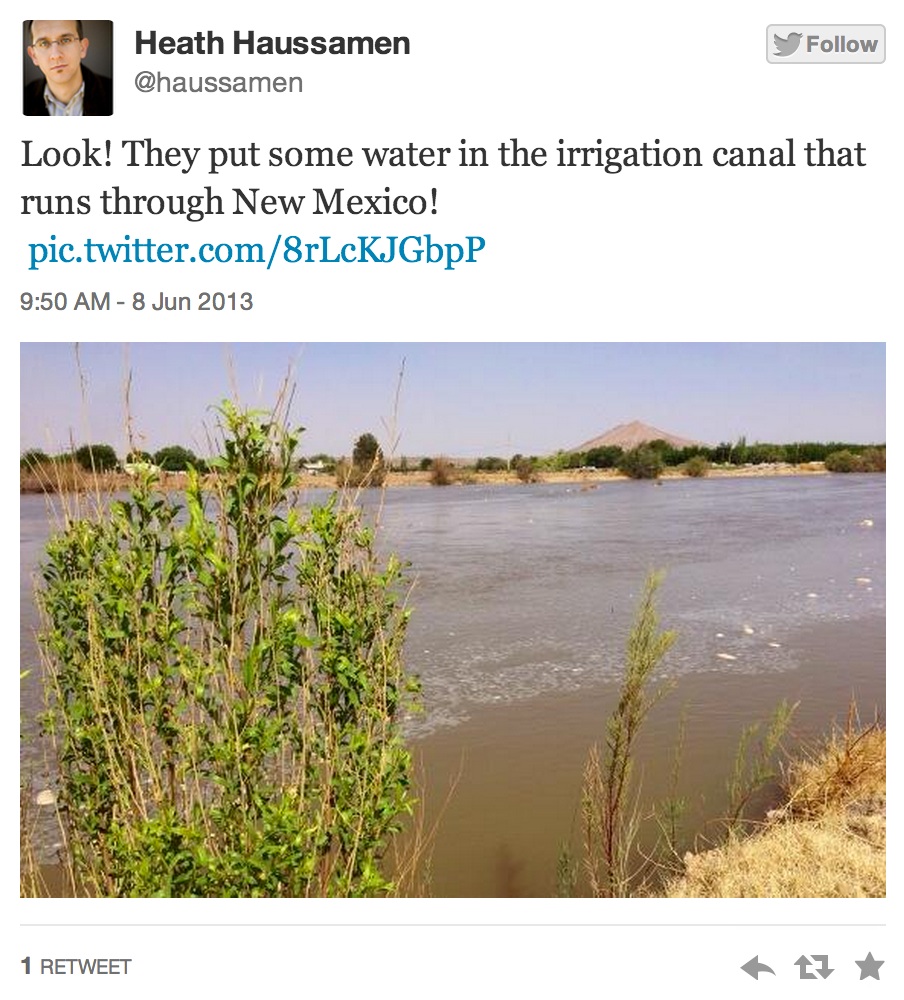

Down in the valley, along the Rio Grande, lesser nighthawks are relatively common. They’re a fun bird, showing up around dusk and chasing insects, looking like a long-winged bat, kinda flappy. I’ve only seen them six times at my house, and when I’ve seen them it’s never been more than a quick look. Tonight, I watched them come and go for an hour, swooping and flapping and hunting their hapless insect prey.

Cliff swallows are incredibly common in Albuquerque’s flood control system and along the river, nesting on the underside of bridges. But I’ve only seen them eight times at my house, and again, never for more than a quick look. This evening, we saw a cliff swallow in the front yard as we got home around 6:30 p.m., and there was a pair around off and on until dark – 8:30-ish. That’s never happened before.

So. Two bug-chasing birds that are normally found regionally, but not commonly in this locally distended part of the suburban ecosystem, show up this evening and hang around. Of course, being obsessed with the topic, I blame drought. If I was smarter, I’d probably just chalk it up to coincidence in a noisy data set.

.