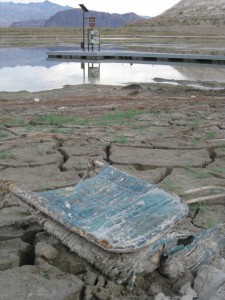

Lee’s Ferry. Photo by John Fleck

By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

As the Colorado River Compact Commission’s negotiators returned to their task on the morning of Nov. 13, 1922, the shape of the compact was beginning to emerge into view.

Colorado Compact Commission Chairman Herbert Hoover opened the meeting by returning to the unresolved question from the previous evening – “whether we could accept a general principle of a division between the upper and lower states of the primary basis of compact?”

Arizona’s Winfield Norviel responded in the affirmative: “We in Arizona are perfectly willing to accept in principle the division of the basin into two divisions.” He went on to make it very clear that in accepting a two-basin compact, Arizona was not accepting a “fifty-fifty partition of the waters,” adding that “I think the fifty-fifty proposition is infeasible and impossible as a matter of exactitude.”

Where to draw the line between an “upper” and “lower” basin

The discussion then turned to the point of division and the status of the Paria River. Carpenter explained that in his compact proposal, he had assumed the division would be the “old Lee’s Ferry.” Norviel the pointed out that Lee’s Ferry is just upstream of the confluence with the Paria and because of the steep canyon terrain, there were no practical gaging locations below the confluence. After a bit more discussion about gaging, Utah’s Caldwell concluded that from his perspective, the Paria River was an upper division tributary and that there was no problem with using two gages, one on the main Colorado River and a separate gage on the Paria (the situation we still have today). Hoover summarized the consensus as follows; the dividing point between the basins would be the proximate location of Lee’s Ferry, but include the Paria River, and the details would be left to a drafting committee.

But how much water should pass the chosen point?

Hoover then turned the Commission’s attention to the question of the upper river’s delivery at Lee’s Ferry. (Note that, at this point in the negotiations, the terms “Upper Basin” and “Lower Basin” were not being routinely used. They used several similar terms interchangeably – upper and lower divisions, upper and lower territories, and upper and lower river or states.)

Hoover put it this way – “the question is whether there be a positive delivery every year, or whether there should be only a delivery of a total over ten years or over three years or over five years or any other period.”

The discussion that followed was largely a two-way dialogue between Norviel and Carpenter, interrupted occasionally by Hoover to summarize or refocus the discussion, and by Arthur Powell Davis and R.E. Caldwell to add or clarify technical points. Carpenter detailed why he picked ten years. He thought it was the “sweet spot” – neither too short to be a problem for the upper river nor too long to be a problem for the lower river.

Carpenter explained that Norviel’s concern that a ten-year average would allow the upper river to deliver nothing for a year or more was not realistic and that development in the upper river would naturally flatten the hydrograph, a point the engineers in the room generally agreed with. Arizona’s Norviel remained skeptical, never agreeing to any period greater than three years The combination of a ten-year flow plus an annual minimum remained an attractive option for the others, especially Nevada’s James Scrugham and Wyoming’s Frank C. Emerson. Carpenter agreed in concept but opposed a suggestion the minimum be set at five million acre-feet per year.

Hoover recessed the meeting, suggesting they take a long lunch, noting it was hard to sit for two-and one-half hours. The Commission adjourned until 3 PM.

That “crackpot” Maxwell

The Commission reconvened at 3 PM. The meeting began with Secretary Stetson submitting a long letter to the record from George H. Maxwell, Executive Director of the National Reclamation Association (now the National Water Resources Association). Maxwell demanded that they delay negotiating a compact and instead turn their attention to the construction of flood control storage facilities to protect the Yuma and Imperial Valley projects. Maxwell, whom Hoover considered a “crackpot,” was one of the people he wanted to keep out of the negotiations. The Commission had adopted a policy of voting on who could join their meetings as advisors. After accepting the Maxwell letter for the record, they voted to admit L. Ward Bannister, a water attorney from Denver, as an advisor to Carpenter.

During the remainder of the afternoon, the Commission exchanged views on several topics, including the term of the compact, the status of the Gila River, and the concept of a minimum annual flow at Lee’s Ferry. Carpenter stressed his view that any minimum flow should be tied to drought in the upper river and “should result in the penalty of drought being equally distributed over the entire river system.” The meeting adjourned at 6 PM to be resumed on Tuesday morning at 10 AM.