beavers

There’s a little concrete check dam in Albuquerque’s riverside woods at the bottom of a pond built by humans as wildlife habitat. Among the wildlife that has taken up residence is a family of beavers, who have built a palatial home on the island in the middle of the pond. But they seem dissatisfied with the workmanship of the dam, and have been making their own helpful additions (the stick in the center has characteristic beaver chew marks on the upper end):

Praise be to the gods of storytelling

update: A helpful reader had a correction: Hub Moeur was Gov. Moeur’s, nephew, not his son. Rats.

previously: This evening, I snapped to the fact that J.H. “Hub” Moeur, the Arizona attorney who as chief counsel for the Arizona Interstate Stream Commission filed the 1952 brief in the seminal Colorado River case Arizona V. California (because Arizona was afraid California would take too much Colorado River water) was the son of B.B. Moeur, the Arizona governor who in the 1930s dispatched National Guard Troops to block construction of Parker Dam (because Arizona was afraid California would take too much Colorado River water).

As an old newspaper colleague used to say, you can’t make up shit that good.

the first rule of journalism

always get the name of the beer:

On my way home from work, I picked up a six-pack of Saison 88, a beer produced by Santa Fe Brewing Co. The advertised alcohol content is 5.5 percent.

Why fighting over water isn’t a bad thing

As I learn about the development of large-scale water management institutions in regions other than my own (the southwestern United States), I’m increasingly convinced that our oft-discussed tradition of conflict – Marc Reisner famously described the Colorado as “the most legislated, most debated, and most litigated river in the entire world” – may really be viewed as a strength rather than a weakness.

Why? Because all that messiness has in fact led to the creation of set of well-established and relatively effective institutions for managing conflicting demands for scarce resources. (I lay out the argument in more detail here.) I was reminded of the issue today by some comments in an excellent piece by Tom Henry of the Toledo Blade about the development of similar institutions around the Great Lakes:

The lakes’ usage has drawn more attention in recent years from politicians and legal scholars, such as those who attend the University of Toledo college of law’s renowned Great Lakes water-law conference each fall. They have stated on numerous occasions that Great Lakes water-management laws pale in comparison to those of the American Southwest, where political battles over water rights have been fought for decades.

Scholars believe this region’s legal framework is evolving into a stronger one as water controversies and more political battles heat up, as evidenced by intense negotiations that resulted in the Great Lakes region’s first binding water-management compact.

Stuff I wrote elsewhere: farming cottonwoods

Here’s another look into the western water solution space – an agreement on the Lower Rio Grande under which willing farmers will have a chance to sell their water rights for use recreating lost riparian habitat (story behind survey wall for non-subscribers):

To the list of the Lower Rio Grande’s famous crops, like Hatch’s chile and Mesilla’s pecans, you’ll soon be able to add cottonwoods and Goodding’s willows.

The Elephant Butte Irrigation District board of directors last month approved an agreement that allows farmers to sell water rights so the water can be used to help grow riverside vegetation.

The deal, negotiated over the last decade by environmental groups led by the Audubon Society and the irrigation district’s farmers, is the largest New Mexico example to date of a growing effort across the western United States to reclaim water for riverside environments.

As the last line suggests, there are lots of different ways to do this. In the LRG case, the Bureau of Reclamation quite literally issued a finding that the cottonwoods would be treated just like any other crop, including sharing shortages in times of drought.

Creeping toward shortage on the Colorado River

The latest monthly Colorado River water management report from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (pdf) takes a major step toward the river’s first ever shortage declaration. We’ll know more in a month, but the preliminary estimates now show drops in the level of Lake Powell by the end of this year could trigger provisions of a six year old shortage sharing agreement among the seven Colorado River Basin states that allow a reduction in releases in the 2013-14 water year from Powell, the reservoir spanning the Arizona-Utah border. That, in turn, would mean less water downstream for Lake Mead, which significantly increases the odds of reduced water availability for Arizona and Nevada in the 2015-16 time frame.

Got all that?

This is a classic example of the sort of institutional plumbing that drives water management on the Colorado River. We mostly talk about the physical plumbing – Hoover and Glen Canyon Dam, the Colorado River Aqueduct, the All-American Canal and the like. But the institutional plumbing – the nested set of principles and agreements, compacts, laws and court decisions established over the years collectively known as the “Law of the River” that governs who gets how much water, and when – is equally important, if not more so.

The key piece of institutional plumbing in the coming shortage discussions is the Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, often called the “2007 shortage sharing agreement”. It’s Byzantine, with complex tables of “if Lake Powell’s got x water in it and Lake Mead’s got y water in it, do z” kinds of directives for managing the system. I can’t begin to give a full explanation of the details here, but it’s important to highlight a central feature: Everyone agreed to this. This is not a case of the federal government imposing a water management scheme on the states, or someone suing and persuading a judge to impose the rules. It was the product of negotiation, a collective recognition on the part of each state (and the federal government) that a deal that provided some certainty, even unpleasant certainty, was better than the previous uncertainty over what would happen in a shortage, and the downside risk of losing a legal fight at that point. This is the users of a common pool resource developing the institutional arrangements to collectively manage that resource.

With that as a preface, here’s a timeline of what happens next:

- August 2013: The Bureau of Reclamation makes its best estimate of how much water Lake Powell will have as of Jan. 1, 2014. That estimate is based on the monthly runoff forecasts and normal releases – 8.23 million acre feet of water released from Powell over the Oct. 1 2013-Sept. 30 2014 water year for use in California, Arizona and Nevada. If inflows are low, and those normal release rates would drop Lake Powell’s surface elevation below 3,575 feet above sea level come Jan. 1, 2014, that would trigger a provision under which water is held back in Powell, reducing releases for use in California, Arizona and Nevada. Instead of 8.23 million acre feet, the Bureau of Reclamation would release only 7.48 million acre feet in the 2013-14 water year. It’s called the “Mid-Elevation Release Tier”. The shortage sharing agreement calls for such a decision to be made in August. The preliminary numbers released last week include an estimate of 3,574.97 come Jan. 1. “Based on analysis of a range of inflow scenarios,” the latest Bureau report concludes, “the current probability of realizing an inflow volume that would result in the Mid-Elevation Release Tier in 2014 is slightly greater than 50 percent.”

- 2013-14 water year: With 750,000 acre feet less of water flowing in, a Mid-Elevation Release Tier declaration means Lake Mead would then end the 2014 water year with a surface elevation of 1,081 feet above sea level, according to the Bureau’s latest numbers, more than 8 feet lower than if there is a full release from Powell. That would be the lowest Mead’s been at the end of a water year since 1936 (data here), setting the stage for the first ever shortage declaration the following year.

- 2014-15 water year: With Powell forecast to stay low, a second Mid-Elevation Release Tier year would likely follow, leaving Lake Mead 10 feet lower by the summer of 2015. In August 2015, a similar projection to the one described above will be done for Lake Mead. If it shows Mead below 1,075 feet above sea level the following year, a formal shortage will be declared and deliveries to Arizona and Nevada will be reduced incrementally to save water. (I’m a little confused about whether the reduced deliveries would kick in at the start of the water year – Oct. 1, 2015 – or on the following Jan. 1. If you’re steeped in the Law of the River and know the answer, leave a comment or email me at jfleck@inkstain.net.)

I apologize for the complexity. If I can find a simpler explanation, I’ll get back to you, or maybe write a book.

Texas drought: it’s all about the soil moisture

Brett Walton explains new research on the water lost in the Great Texas Drought of 2011. It’s a lot. But the thing that caught my eye was where most of the water loss occurred:

“Groundwater depletion can be significant locally. However, by taking Texas as a whole, most water depletion comes from soil moisture during drought,” Di Long, lead author on the paper, told Circle of Blue.

Tree rings suggest strong ENSO response to greenhouse forcing

A new paper in Nature by Jinbao Li and colleagues, using tree rings to create an El Niño/La Niña (the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO) reconstruction of unprecedented fidelity, suggests an increase in ENSO in the second half of the 20th century:

Our data indicate that ENSO activity in the late twentieth century was anomalously high over the past seven centuries, suggestive of a response to continuing global warming. Climate models disagree on the ENSO response to global warming, suggesting that many models underestimate the sensitivity to radiative perturbations.

(For more on the insanely cool usefulness of tree rings, you should buy my book.)

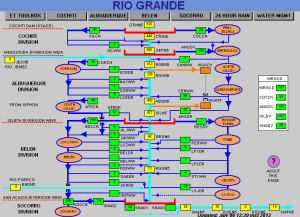

Rio Grande as plumbing

Doing daily journalism on the declining Rio Grande, I have frequent occasion to use this handy tool from the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District and the Bureau of Reclamation. It gives close-to-real time readings on all the main river and irrigation system gauges:

It occurs to me that its crisp reductionism rather supports my recent argument that the Rio Grande is plumbing.