My name’s John, and I’m a water law junkie. I can’t get enough of Article III(d) of the Colorado River Compact. I love picking fights over the Upper Basin’s share of Mexico’s 1.5 million acre feet delivery obligation. I don’t care. I’ll argue either side. Just give me my fix.

So I’ll happily stipulate that under the Law of the River, Arizona’s junior water rights mean that as climate change saps the Colorado’s flows, the Grand Canyon State will see its allotment cut to zero before California loses a drop. That’s what the water law says, right? Mainline.

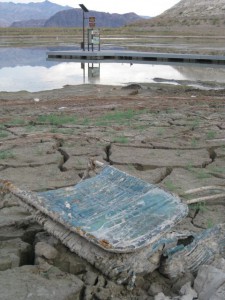

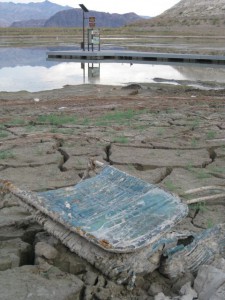

Boulder Harbor, Lake Mead, Oct. 18, 2010

This is why Friday’s talk by Brad Udall, head of the University of Colorado law school’s Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment, was the most interesting thing I heard in two very interesting days of talks on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most significant water law ruling, period, in the case of Arizona v. California.

Udall stood up before a room full of lawyers, law school professors and water managers and said, in essence, that water law doesn’t matter. OK, that’s a rhetorical overstatement of a nuanced point. What Udall was really saying is that there’s a world inhabited by water law junkies like me that accepts the reality that, for example, Arizona’s junior rights mean its Central Arizona project, which represents half of its Colorado River entitlement and delivers water to Phoenix and Tucson, gets cut off completely before California loses a drop. And then there’s “the reality of the public” where people, faced with such a situation, are going to say, in essence, “WTF?” (my initialism, not Brad’s)

Udall’s “reality of the public,” as distinguished from the “reality of the water community”, is a world in which regular folk have no clue about all this Article III(d) and Colorado River Basin Storage Project Act and “doctrine of prior appropriation” stuff that we water nerds so venerate. They just want to turn on the tap and have the water come out. But they have some basic notions of fairness and good sense, imagining that the policies underlying our attempt to supply that water will consider questions of equity, sound economics and the environment. Water management actions that violate those notions will, to quote Udall, “violate the public’s sense of ‘rightness'”.

This means several things in terms of practical Colorado River Basin management.

It means that, whatever the Law of the River says, as a practical matter we’re not going to let the level of Lake Mead drop below 1,000 feet above sea level, the elevation at which Las Vegas can no longer get water from the reservoir. Udall had a slide in his talk quoting Mike King, head of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources: “I don’t care what you think about the Law of the River, we are not going to dry up a city of 2m people.” And even if/when Las Vegas gets its “third straw” built to protect its diversions at low lake levels, “the reality of the public” is not likely to tolerate drying up a lake that 8 million people enjoy every year.

It means, as I suggested above, that Udall thinks folks won’t tolerate a situation in which Arizona loses all its CAP water while California continues to take a full allotment.

And it means, Udall argued, that the states of the Upper Basin will not be left to take the full brunt of the river’s shrinkage because of climate change while the Lower Basin gets its full Compact share.

Udall offered some suggestions for what might happen in the alternative – creative new ways of sharing shortages; Californians, especially their big ag users, are going to have to do some of the sharing, and the three “E’s” – equity, economics and environment – will have to be on the table, even if they don’t have a specific “Law of the River” claim.

But here’s the key point: the solutions involve people who have no idea about all the “Law of the River’s” legal niceties: they’re going to want the water distributed in a way that make sense to them.

updated: To correct misstatement about Arizona’s priorities. Only CAP water is junior to California, not all Arizona’s river water.