A snowy egret showed up this afternoon amid the turtles sunning themselves on the Rio Grande Nature Center’s pond. We took some pictures.

[slideshow_deploy id=’8238′]

Stuff I wrote elsewhere: the Rio’s smell

Corky Herkenhoff, who’s been farming at San Acacia for half a century, told me he can tell where the runoff is coming from by the smell. San Acacia sits just below the Rio Puerco and Rio Salado, two generally dry tributaries that have been pumping water into the Rio Grande over the last week. Herkenhoff said he can tell the difference. “You can tell when the Rio Puerco comes in, and you can tell when the Rio Salado comes in,” he said.

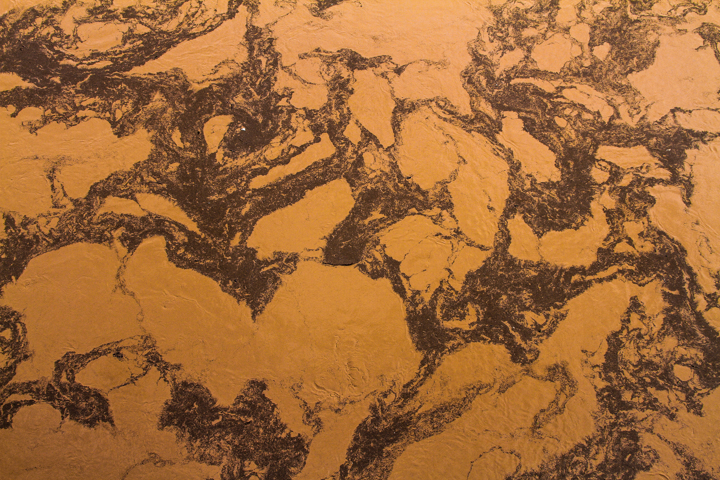

Muddy river

Chasing water in the desert: the great Rio Grande “flood” of 2013

In the midst of a very unusual storm (see my newspaper explanation of its unusualness here), I’ve spent much of the last 24 hours watching a big slug of water make its way down the Rio Grande Valley in which Albuquerque sits. A source yesterday afternoon pointed me to the readings on the USGS San Felipe gauge, which had popped up over 9,000 cubic feet per second. For this spot on this river, upstream from Albuquerque, that is a lot of water. We quickly committed journalism, the water managers rallied their modelers and calculated estimated peak flows and arrival times, the municipal authorities went into hyperdrive. And then we waited.

This was not a “wall of water” type of flow, but as modeled, it was likely to be up near the largest flow we’ve had in Albuquerque in the post-dam era. So we staked out the bridges, as did a hoard horde of residents, to watch our briefly big river roll past. (My colleague Rob Browman illustrated this part nicely.)

After work, Lissa and I went out in the pitch dark so she could see it, and then I spent today following the pig in the python downstream. It’s a slow-moving, easy-to-track thing: midnight at Albuquerque’s Central Avenue bridge, noon today at Los Lunas south of here, rising as I write this at Bosque, the gauge in the far southern end of Valencia County.

The thing that was hard to capture was the quiet nature of the event. We think of “floods” as tempestuous, but as I wrote this morning, one of the reasons the flow was less than expected is the way the river spread gently into the woods alongside its main channel. Upstream, the river has been incising into its old flood plain, so the spreading is only possible in places where human intervention, in the form of habitat restoration, has created low areas, swales and side channels for endangered critters. To the south, the river made it out of its banks on its own.

I am not a photojournalist, but I’m trying to learn how to take pictures that tell stories. Here’s one attempt, a cottonwood in a normally dry bosque forest with a soft blanket of water at its feet:

“bronze buckshot” at the MWD

There are no silver bullets for dealing with the west’s water problems. There is instead, as several speakers said last week at a workshop I attended, “bronze buckshot”.

The Metropolitan Water District board yesterday handed out 16 grants to local Southern California water agencies that looked very much like what this metaphor implies – lots of small projects targeted at funding preliminary work on lots of little local solutions:

- $180,000 to Glendale to study technology for removing hexavalent chromium, cleaning ick out of existing groundwater reservoirs

- $200,000 for an Orange County study of conjunctive management of storm water, desal and other techniques in basins with impaired groundwater

- $125,000 to the San Diego County Water Authority for work on indirect potable reuse

- a scattershot of money to a bunch of different agencies to develop direct potable reuse communications strategies

And the list goes on (staff report in pdf here).

This is the sort of thing that makes me hopeful about our ability to cope with western water’s supply-demand imbalance. Southern California has long confronted the reality of growing demand and constrained supply. They were among the first to come up with aggressive joint management of their groundwater basins (pdf), they built extraordinary water importation systems (this isn’t going to all be “soft path” stuff), and they managed far better than anyone expected when they had their Colorado River supplies curtailed a decade ago.

When you face the prospect of running out of water, you do stuff. Sometimes big things, sometimes lots of little things. But you do stuff.

Stuff I wrote elsewhere: water management tools we learned in kindergarten

The (San Juan) basin, in northwestern New Mexico, has every competing water interest you’d want in the mix if you were creating a recipe for conflict: Native American water rights (the Navajo and Jicarilla Apache nations), endangered species (the Colorado pikeminnow and razorback sucker), farming large and small, city water use and a couple of big coal-fired power plants. Also, not one but two interstate water compacts lurk in the background.

As Navajo Reservoir on the San Juan River dropped, the risk of conflict was enormous.

“We were looking into an abyss,” Leeper said.

But rather than fire up the lawyers and prepare to fight over the dwindling supplies, the basin’s water users began talking. When 2003 started looking every bit as dismal, they had a negotiated agreement in place to share the shortages.

Water theft

The Times-Standard in Humboldt County (northern California) reports that someone swiped 20,000 gallons of water. From a school:

Bridgeville Elementary School was reopened Wednesday after being forced to close for a day when staff discovered up to 20,000 gallons of water had been stolen from an onsite water tank during the Labor Day weekend.

”There were tire tracks in the field on the south side of the school,” Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Lt. Steve Knight said. “The school staff believes someone climbed the fence, and used a school garden hose to drain the tank.”

Knight said it is believed a water truck or large truck and trailer with water tanks were used in the theft. He said the reason behind the theft is unknown.

Who’d do such a thing? Bruce Ross, who commits journalism for a living in that part of the country, offered this hypothesis:

Just a few weeks till pot harvest. RT @jfleck: In California, a case of water theft: http://t.co/xd6g8peSBE #cawater

— Bruce Ross (@bross_RS) September 6, 2013

Rio Not

Albuquerque’s Rio Grande is currently not much of a river.

River No More: the Rio Grande as seen from Albuquerque’s west bluff neighborhood, Sept. 8, 2013, by John Fleck

Lissa and I made the rounds this afternoon of a few Rio Grande viewpoints. This is from Albuquerque’s West Bluff neighborhood, on the west side of the river north of downtown. The bridge in the distance is Montaño.

With an abysmal snowpack, the river was dropping fast in June, but a wet July rescued flows temporarily. As August dried out, though, the river started dropping again. The gauge at Central Ave., the most important measure for regulatory purposes, is down this weekend, but the Paseo del Norte gauge, at 137 cfs, is the lowest it’s been all year. The Central gauge has typically been 50 to 100 cfs below the Paseo gauge all year (data here), so I’d only be guessing based on past performance that the Central flow well south of 100 cfs. Eyeballing it from around Central, it sure looked lower than in early July, when it briefly reached the mid-70s.

Maybe it’ll rain this week.