By Jack Schmidt (1), John Fleck (2), Kathryn Sorensen (3), Eric Kuhn (4), Katherine Tara (2) | March 21, 2025

1 Center for Colorado River Studies, Utah State University

2 Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico

3 Kyl Center for Water Policy, Arizona State University

4 (sort of) retired

In Short:

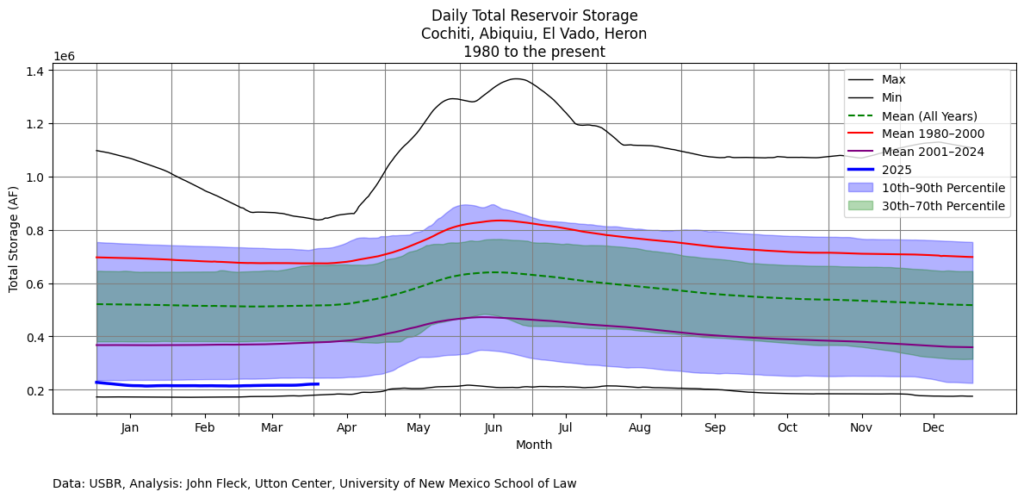

Since the onset of the Millenium Drought 25 years ago, water agencies in the Colorado River Basin have been challenged by the overwhelming, yet essential, tasks of balancing total water use with a reduced supply and recovering some of the reservoir storage lost since the last time the system was relatively full in summer 1999. By monitoring long-term changes in basin-wide reservoir storage, we can readily judge the success of these efforts.

In mid-March 2025, total storage in 46 reservoirs tracked by Reclamation was the third lowest in the 21st century for this time of year. The total amount of storage was the same as it was in late July 2021 when water managers described the situation as “serious” and declared a shortage in Lower Basin water supply. Between late July 2021 and mid-March 2023, water storage further plunged to an unprecedented low, but the exceptional runoff of 2023 provided modest recovery. However, basin storage in mid-March was 2.79 million acre feet, or 9%, less than the summer 2023 peak. In mid-March, 33% of the basin’s storage was in Lake Mead, 29% was in Lake Powell, 29% in 42 federal and non-federal reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell, and 9% in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu. Water has been accumulating in Flaming Gorge Reservoir since early February and throughout the winter in a few smaller Upper Basin facilities but has been withdrawn from other large federal Upper Basin facilities and from Lake Powell. Lake Mead has been going down since late February. It is likely to be that total basin reservoir storage will decline until the beginning of the 2025 snowmelt runoff season and will only modestly recover, because inflow this year is forecast to be below average and less than in 2024.

System conservation and Assigned Water development by the Lower Division states and Mexico have prevented storage in Lake Mead from being even lower than what it is today. However, recent Reclamation projections indicate that consumptive use in the Lower Basin in 2025 will be larger than in 2024, suggesting that basin reservoir storage at this time next year will be even less than it is today. Projections of Upper Basin consumptive use are not available at this time. The continued decline and lack of recovery of water in reservoir storage conveys the clear message that our efforts to balance use with supply and to recover storage have not succeeded. The Colorado River water crisis endures.

In Detail:

On 15 March, active storage in 46 reservoirs in the Colorado River watershed that are tracked by Reclamation in the Bureau’s Hydrodatabase[1] was 26.9 million af (acre feet), the same amount as on 21 July 2021 (Fig. 1). That amount was the third lowest total basin storage on 15 March of any year of the 21st century[2] and is approximately 45% of the total stored in these reservoirs the last time the basin’s reservoirs were relatively full in late July 1999[3]. On 15 March, 33% of the basin’s storage was in Lake Mead, 29% in Lake Powell, 29% in 42 reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell, and 9% in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu[4]. These data remind us of the challenge in providing a secure and reliable water supply to the Southwest, southern California, and northwestern Mexico.

Figure 1. Graph showing total reservoir storage in 46 reservoirs reported by Reclamation in its Hydrodatabase (blue line), as well as the contents of Lake Mead and Lake Powell (orange line), 42 reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell (green line), and in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu (red line). Data are between 1 January 1999 and 15 March 2025. Total basin reservoir storage today is the same as in late July 2021.

It is instructive to remember how today’s small amount of reservoir storage was viewed when it occurred in summer 2021. On 27 July 2021, The New York Times posted the headline, “Two of America’s largest reservoirs reach record lows amid lasting drought.” That story led with these words, “The water level in Lake Powell has dropped to the lowest level since the U.S. government started filling the enormous reservoir on the Colorado River in the 1960s — another sign of the ravages of the Western drought.”[5] In the article, Wayne Pullan, Reclamation’s Upper Colorado Basin Regional Director, said, “This is a serious situation,” and Brad Udall said, “I’m struggling to come up with words to describe what we’re seeing here.” In mid-August 2021, Interior formally announced a water shortage in Lake Mead, triggering cuts on water deliveries, especially to Arizona farmers.

But today, there is less discussion about whether this small amount of reservoir storage represents a crisis. In part that may be because the season of snowmelt is ahead of us rather than behind us, as was the case in late July 2021. We hope that inflow this coming spring will recover some storage, but, this winter’s snowpack is merely average[6], and the basin’s soils are very dry. The Bureau of Reclamation’s “most probable” forecast of unregulated inflow to Lake Powell in 2025 is only 6.77 million af[7], 70% of the 30-year average and less than in 2024. Additionally, there may be little sense of concern, because we survived these conditions between July 2021 and March 2023. In fact, total basin storage plunged to only 21.3 million af in mid-March 2023. Perhaps, we are distracted by the engineering, legal, and political intricacies of the negotiations concerning post-2026 consumptive use and the seeming dysfunction of those negotiations. Perhaps, we are resigned to low reservoir storage as the new normal. Perhaps, we are the frog in the pot of water whose temperature is gradually rising, and we do not realize the water is about to boil.

Although significant strides have been made to conserve water, further reductions in water use throughout the basin are necessary, should we experience a succession of very dry years such as occurred between 2002 and 2004 and between 2020 and 2022. The post-2026 negotiations primarily have focused on strategies to reduce basin consumptive uses to match the 21st century’s declining supply, but today’s small amount of storage reminds us that it is critically important to also develop policies to recover reservoir storage to ensure security and reliability of the system.

To date, it has been exceptionally hard to recover storage. Despite the Lower Colorado River Basin System Conservation and Efficiency Program, the Upper Basin System Conservation Pilot Program, the Drought Response Operations Plan, Assigned Water development programs and large expenditures to reduce consumptive use using the Inflation Reduction Act, the Basin’s water managers have made no progress in rebuilding storage except that provided by the unusually large inflows of 2023. Between mid-July 2023 and mid-April 2024 (immediately prior to the onset of spring snowmelt inflows), the basin’s reservoirs were only drawn down by 2.2 million af, the smallest drawdown of total basin storage of the last 15 years[8]. However, the winter 2023/2024 snowpack yielded below average inflow to Lake Powell, and the basin only gained 2.5 million af of storage (Fig. 2). As of 15 March, the 46 reservoirs of the basin have been drawn down by 3.1 million af since the peak storage of those reservoirs in mid-July 2024. During the remainder of March and part of April, reservoir drawdown will continue to deplete storage originally accumulated in 2023.

Figure 2. Graph showing reservoir storage in different parts of the Colorado River basin between 1 January 2021 and 15 March 2025, summarizing periods of increase and decrease in total storage. Lake Mead, Lake Powell, and the 42 reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell each store approximately 30% of basin’s total storage.

Low storage in Lake Mead persists despite 3.94 million af of water savings by the Lower Colorado River Basin System Conservation and Efficiency Program since 2006 (Fig. 3) and despite approximately 3.7 million af of Assigned Water development. Although additional savings are needed in 2025, the prospects of significant savings are not encouraging. Water users in the Lower Basin and Reclamation measure actual use and forecast trends in real time, and we anticipate 6.5 million af of main stem consumptive use by the three Lower Basin states. Commendably, this is less than the states’ nominal 7.5 million af/yr allocation under the Supreme Court defined allocation. Arizona is expected to take the largest share of those cuts, with projected main stem use of 2.1 million af, 74% of its nominal allocation. Nevada is projected to use 68% of its 300,000 af allocation, and California is projected to take 96% of its 4.4 million af allocation.[9] However, the Lower Basin’s projected 6.5 million af use is more than last year’s 6 million af of use. It is unclear the extent to which use in 2025 might fluctuate based on the available of federal funding to compensate water users for their conservation efforts, given the uncertainty enveloping federal policies under the new administration. We have no comparable set of numbers that allow evaluation of anticipated Upper Basin use and actual savings of wet water.

Figure 3. Graph showing water conserved in Lake Mead resulting from the Lower Colorado River Basin System Conservation and Efficiency Program and conservation efforts in Mexico.

Deficit spending is likely to continue between now and mid-April and will primarily be from Lake Mead and Lake Powell, because the total storage in the 42 reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell is no longer being depleted[10]. The basin-wide spatial pattern of reservoir operations in late winter and early spring 2025 has been storage of water in small upstream reservoirs and continued withdrawal of water from some CRSP facilities including Lake Powell, and recently from Lake Mead. Draw down continues at Granby (the primary storage facility of the trans-basin Colorado-Big Thompson Project), Blue Mesa, Navajo, Fontenelle, and several smaller reservoirs[11]. These Upper Basin depletions have been somewhat offset by small amounts of accumulation at other reservoirs[12]. Flaming Gorge Reservoir, the largest facility upstream from Lake Powell, was at its lowest at the very end of January and increased 41,100 af of storage in February and the first half of March. In contrast, the total contents of Lake Powell and Lake Mead continue to be drawn down. Lake Powell was at its highest on 1 January 2025, has lost 803,000 af of storage since that time, and will probably continue to decline for another month, based on projections by Reclamation[13]. Lake Mead increased in storage after 1 January, peaked in late February, and subsequently lost 74,000 af. Last year, storage in Lake Mead continued to be lost until early August, and the same pattern is likely this year. The total loss of storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead between 1 January and 15 March was 476,000 af. The rate of loss from the Mead-Powell system for the next few weeks will be determined by the balance between inflows to Lake Powell and releases from Lake Mead.

[1] Data are accessed at https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/hydrodata/reservoir_data/site_map.html.

[2] Total active storage in the same 46 reservoirs on 15 March 2025 was less than on the same date in 2022 (23.5 million af) and in 2023 (21.3 million af).

[3] On 21 July 1999, total active storage in the same 46 reservoirs was 59.5 million af.

[4] Lake Mead stored 9.01 million af, Lake Powell stored 7.85 million af, the 42 reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell stored 7.74 million af, and 2.30 million af were in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu on 15 March.

[5] On 27 July 2021, active storage in Lake Powell was 7.90 million af, approximately the same as today.

[6] On 20 March 2025, snow water equivalent (SWE) in the Upper Colorado Region was 97% of median with 18 days remaining until the annual peak SWE typically occurs.

[7] Reclamation’s 5 March 2025 forecast.

[8] This comparison is for the reservoir drawdown between the mid-summer peak and the following spring’s minimum storage prior to the next year’s runoff. The smallest draw down of total basin reservoir storage in the recent 15 years was between 13 July 2023 and 17 April 2024 (2.15 million af). The second smallest drawdown was 2.61 million af between 6 July 2014 and 4 May 2015. Drawdown was 2.56 million af between 4 August 2011 and 30 April 2012 and was 2.82 million af between 28 July 2019 and 29 April 2020.

[9] Reclamation Lower Colorado River Basin forecast, 17 March 2025 https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/hourly/forecast.pdf

[10] Maximum draw down of these Upper Basin reservoirs was 1.49 million af on 26 February 2025.

[11] Net drawdown exceeding 1,000 af between early January and mid-March occurred at Granby (69,600 af), Williams Fork (6,570 af), Dillon (4,520 af), Green Mountain (8,940 af), Ruedi (5,310 af), Taylor Park (1,790 af), Blue Mesa (17,200 af), Fontenelle (54,100 af), Upper Stillwater (1,230 af), and Navajo (28,400 af) Reservoirs.

[12] Reservoirs accumulating more than 1,000 af storage between January and mid-March were Willow Creek (1,300 af), Rifle Gap (2,600 af), Vega (1,400 af), Crawford (1,750 af), Big Sandy (1,670 af), Eden (1,150 af), Meeks Cabin (2,290 af), Red Fleet (1,030 af), Steinaker (2,910 af), Strawberry (7,050 maf), Starvation (15,200 af), Moon Lake (3,180 af), Scofield (4,950 af), and Vallecito (6,060 af) Reservoirs.

[13] Based on the March 2025 24-Month Study Projections https://www.usbr.gov/uc/water/crsp/studies/images/PowellElevations.pdf.