Pooling our resources to discover new truths about the universe so that we can all have better lives, to strike back against disease, suffering, poverty, and violence, to reduce ignorance for the benefit of all—that’s literally the most badass thing we do.

A legal guide for climate scientists to safeguard their on line communications

With the new administration’s shithousery team now pounding on NOAA’s door, a useful resource from the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund:

Emails sent to and from scientists are increasingly subject to scrutiny through a variety of means, including aggressive open records requests, subpoenas, and even hacking. The prevalence of social media, blogs, and other digital platforms and forums have also made scientists vulnerable to new kinds of harassment and attacks.

Shithousery and California’s Success Reservoir

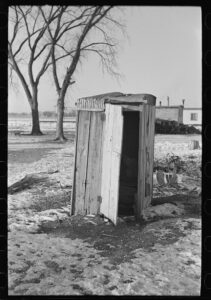

Shithouse, Spencer Iowa, 1936. Photo by Lee Russell, FSA photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public goods are underprovided, and easily lost if we aren’t careful.

There’s a tactic in football (what we Americans refer to as “soccer”) called “shithousery.” It’s a style of norm-breaking behavior – constant stoppages, niggling fouls, feigning injury – that completely disrupts the flow of the game. It can involve bending or breaking rules, and one of its main goals is to disorient the opponent, piss them off, trigger them. Purists hate it, but it often works.

This may be a good framework for thinking about what the new leadership in our nation’s capital did last week at Kaweah and Success reservoirs in California’s southern San Joaquin Valley, dumping a bunch water into a river for a photo/tweet-op. Lois Henry at SJV Water has the goods on the specifics, which defy explanation other than these people are fucking idiots and we just handed them the keys to the bus in which we all must ride. (One of my young internet-native friends suggested that I experiment with shitposting, how’m’I doing? Not my strong suit.)

My water policy community friends and I have been pretty focused in the last few weeks on the language of executive orders, running through how the rules work, where the federal authorities are, how the ESA “god squad” actually functions and might be employed, stuff like that. “Keep your eyes on the process,” I wrote last week.

But is that maybe the wrong frame? Is this shithousery? I was going to write “just” shithousery, but as my trans friends and family will attest, there is real harm here.

Tyler Cowen this morning offered a helpful hypothesis:

Flood the zone. That is how you have an impact in an internet-intensive, attention-at-a-premium world.

Cohen is making an argument that goes beyond the shithousery itself to the shithousery’s goal of moving policy by moving culture. It is not about each specific crazy thing on offer, it’s shithousery aimed at changing the entire game. His post is worth a read.

Clearly the rules don’t matter to these people, which is a bit of a setback to someone who has spent long years trying to master them. But shithousery has earned an enduring place in the beautiful game for a reason.

Terrain vague

The old Schartzman packing plant

Unincorporated margins, interior islands void of activity, oversights, these areas are simply un-inhabited, un-safe, un-productive. In short, they are foreign to the urban system, mentally exterior in the physical interior of the city, its negative image, as much a critique as a possible alternative.

-Ignasi de Solà-Morales Rubió, “Terrain Vague”

In his essay “Terrain Vague,” the architectural and social critic Ignasi de Solà-Morales Rubió points us to the liminal spaces in our cities, between the places where we busily do city things. They are the leftover bits, the abandoned bits, places of both promise and decay.

He’s drawing from the French and playing with textures of meaning in the word “vague”- from the German “woge” – movement, oscillation, instability, and fluctuation; and “vacant,” from the Latin “vacuus,” meaning empty, unoccupied, free, available; and then “vague,” from the Latin vagus, meaning indeterminate, imprecise, blurred, uncertain.

junkyards, to recycle the results

Sunday’s ride on the new bike took us down the Barr canal through Albuquerque’s south valley, east of the river. It once was the meat packing district, when a city needed a meat packing district. The evolution of the modern city has replaced stockyards with petroleum tank farms to fuel a modern city, and junkyards to recycle the results.

But there remain these fragments. The brick building in the picture is the old meat packing plant, storied home of a World War II German prisoner of war camp. (They seem to have been well treated, a historian describes “big jars of mustard” for their sandwiches, no one tried to escape.) The farmland to the left in the picture is still planted in alfalfa, kept in production thanks to our agricultural tax break. Weirdly, taxes would go up if it was just left vacant.

The new bike is well suited for exploring Albuquerque’s terrain vague, its primary purpose.

Encrypted

No particular reason, but I had some time yesterday and asked a young tech friend for help dusting off my Signal account, which I hadn’t used in a while. Should you also be interested – again, no particular reason, just feeling geeky on a late winter day – here’s some info to help you on this journey:

As a federal civilian with some technical know-how, I wanted to share with my fellow colleagues the importance of moving to Signal for messages instead of using other tools like iMessage. There are a few simple reasons why, so we’ll outline them here, and explain how we can all make the switch together. This is a good, concrete step we can all take to keep each other safe.

I’m good, thanks for asking.

New bike day. Meet the Space Ghost.

I got a couple of alarmed emails from friends after the last cryptic blog post, the one about how I can’t be broken.

The post was aimed at a couple friends who I knew would get the reference. I forget that other people read this too, sorry. Your emails of concern made me feel loved, so that’s good.

Love’s good right now.

Context from this IFHT song. It’s a punk rock ear worm (thanks, R!) about a guy whose life is falling apart, but then he gets a new bike:

It’s new bike day and I can’t be brokenIt’s new bike day and I get to ride

I might be broke and alone but there’s rubber and chrome

On new bike day and I feel alive

I can’t be broken.

Keeping eyes on process

Allen Best gives us a good first pass in his niche (the Big Pivot) on the on-the-ground impact of the attempted freeze on Inflation Reduction Act funds on rural electricity in Colorado:

Electrical cooperatives in Colorado have been promised well more than a billion dollars in federal aid through the New ERA program.

The carve-out in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was intended to help electrical cooperatives, who mostly serve rural America, make the energy transition from coal to less-polluting sources. Colorado-based Tri-State Generation and Transmission lobbied hard for the New ERA (Empowering Rural America) funding and will be a major beneficiary. It is in line to get $670 million.

Will the money eventually arrive? Donald Trump in his first days as president ordered a freeze on distribution of funds.

There’s a lot of noise right now, some of it intentionally sown chaos to distract, some of it intentionally created chaos to cause substantive change, and some of it gross incompetence. It’s difficult to tell the three apart, but we need to keep our eyes on the substantive process. That’s what I need from my journalism right now.

Anne Castle steps down as the federal representative to the Upper Colorado River Commission

Worth sharing in full:

January 28, 2025

Re: Resignation as U.S. Commissioner to Upper Colorado River Commission

Dear (addressee redacted)

As requested, I am submitting my resignation as U.S. Commissioner and Chair of the Upper Colorado River Commission, effective January 27, 2025. I was honored to be

appointed by President Biden to this position and serving on the Commission has been a privilege. I am deeply appreciative of the opportunity to contribute to the vital work of managing and protecting the Colorado River.This is an existential time for the river. We are on the brink of putting in place an operating regime that will govern our lives and our economies for decades. We are currently trying to manage an immense river system with tools and structures that were not designed for the conditions we face today. The Law of the River has provided a

stable foundation for over 100 years, and we need to give it credit for the amazing development and thriving populations in the entire southwestern part of the country. But the law has not fully adapted to kind of hydrologic conditions we have seen in the past and expect in the future. Agreements negotiated in good faith decades ago are no

longer providing the intended balance of fairness.The operation of the Colorado River is a complex web. Pulling on one thread of the web vibrates through the entire system, with significant potential for unexpected and

adverse consequences. Sustainable operational solutions must be crafted by those who best understand and appreciate this complexity – the Colorado River Basin States and Tribes, the Bureau of Reclamation and other affected agencies and offices within the Department of the Interior, and the many dedicated stakeholders and professionals who rely on and care about the River.This type of process is slow, messy, cumbersome, and unscripted, but ultimately results in the best path forward. This is the course being followed now. Edicts imposed from outside the Basin, such as recent proclamations concerning California water, based on an inadequate understanding of the plumbing and motivated by political retaliation, upend carefully crafted compromises, create winners and losers, and unnecessarily spawn the potential to adversely affect the lives of millions of people as well as the ecosystems on which they depend.

During my time as the U.S. Commissioner on the UCRC, I have had the opportunity to witness an evolution of role of the 30 Basin Tribes in Colorado River management. The commitment by the UCRC and its state commissioners to greater inclusion of Tribes in decision-making processes and more robust consideration of Tribal interests and issues has been extraordinary and had tangible results. The Memorandum of Understanding between the UCRC and the Upper Basin Tribes cementing adopted processes of cross communication and committing to shared goals is an historic first in the Basin. I am optimistic that, despite the rescission of the Executive Order on environmental justice, progress toward more meaningful participation by Tribes in Colorado River decision-making will continue.

In this position, and in my former role as the Assistant Secretary for Water and Science at the Department of the Interior, I have had the privilege to work with many dedicated and professional public servants within the Department and particularly in the Bureau of Reclamation. Despite being vilified by the very Administration they serve, these federal employees continue to strive to fulfill the mission of their agencies. The abrupt imposition of disruptive new terms of employment and undermining of civil service entitlements and expectations are explicitly designed to result in a wave of resignations, which are unabashedly welcomed by the architects of such policies. This broad brush, unfocused purge in furtherance of the stated goal of liberating large corporations from regulation they do not care for will result in attrition of expertise, damage to the American public, and specifically, a more disordered and chaotic Colorado River system.

I wish only the best for the Upper Colorado River Commission and its Commissioners. Both the staff and the Commissioners are dedicated and hardworking and fully

committed to their responsibilities. I will be cheering their efforts to reach a negotiated operational compromise that will sustain the River in the decades to come.Sincerely,

Anne J Castle

AI as physical and social infrastructure

Seen only as a collection of concrete and light poles, a highway is not racist. But the highway is a system within a system, and its path through a city or town can trace the boundaries set by prejudice. These paths are carved into cities based on decisions that prioritize categories of people through a lens of economic value. Once completed, highways may have been inaccessible to the lower-income communities they had segregated.

Likewise, when biases based on gender, race, and other social traits are baked into LLMs, they perpetuate social and economic inaccessibility in ways indistinguishable from racism or sexism. The word choices predicted by a large language model are paths, too, and are directed by probabilities. Whatever progress has been made in minimizing the bias of these models has been contingent on pressure from policymakers and regulations to ensure it was a priority.