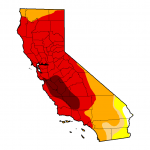

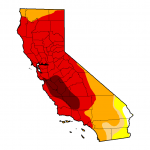

Jan. 28, 2014 Drought Monitor

California, listen to me. (Grabs home state firmly by the shoulders, stares into California’s face intensely.) You can do this. It’s going to be OK.

I know, I know. “Zero” sounds bad. But you go into a drought with the water supply and water system you have, not the one you might want or wish to have at a later time. You’ve got too many people for a year like this, and too large farms and too few water meters and too little groundwater regulation, and it’d be great if we could go back in time and fix that stuff. But those mistakes have already been made – crazy big ones, frankly, but that’s what you’re stuck with.

The thing to remember – and this’ll help you get through the tough year ahead – is that drought is no one big thing. It’s a series of little things – one water user, one water system at a time. That’s how you’re going to get through this. If you focus on “zero” you’re screwed. Think about who’s actually going to be short of water, and what they’re going to do about it.

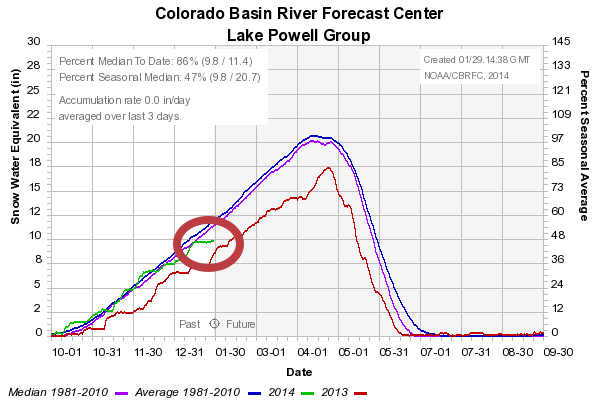

Let’s start with Matt Weiser’s excellent piece in yesterday’s Sacramento Bee, in which he wisely put scare quotes around the word “zero” after the California Department of Water Resources announced a zero allocation for the State Water Project. As Matt explains, “zero” doesn’t necessarily mean “zero”. First of all, it’s a starting point, and could rise if it rains and snows. Second, the State Water Project is only one source among a number for most water users. Some of those other sources are stressed, but “zero” doesn’t mean taps going dry:

The “zero” forecast affects urban and agricultural areas from San Jose to San Diego that depend in part on water diverted from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Most of these areas have other water sources to draw from, including local reservoirs and groundwater wells. (emphasis added)

If you’re a farmer who depends on SWP water, this is a deep bummer. Farmers and the communities around them are going to suffer economically:

The State Water Project serves about 750,000 acres of farmland. Most farmers have access to surface water and groundwater, including private wells, and it’s common for them to be given short allotments in drought years. Before Friday’s announcement, the State Water Project delivery forecast was only 5 percent of the maximum amount allotted in its contracts with water agencies.

Even so, the announcement assures further conservation measures will be required, and may press some farmers to fallow land. (emphasis again added)

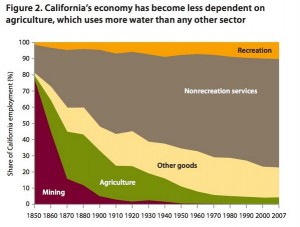

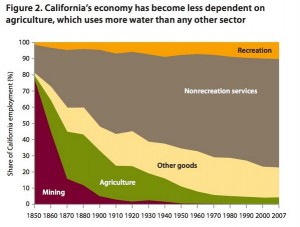

California’s Economy and Water Use. Source: PPIC

If that’s you, this really sucks. But for most of California, that’s not you. From Ellen Hanak and colleagues at the Public Policy Institute of California:

[A]griculture and related manufacturing account for nearly four-fifths of all business and residential water use—but make up just 2 percent of state GDP and 4 percent of all jobs.

But what about the core necessities – water for our sinks and showers and toilets? If you depend on the Shaver Lake Heights Mutual Water Company in Fresno County or 16 other mostly rural water systems around the state identified by the state as facing “severe water shortages in the next 60 to 100 days”, look out. But in a state with 38,332,521 residents, give or take a few, the fact that only 17 relatively small communities have so far been identified as being at risk of running out of water means that the vast majority of the state’s population is currently not at risk of running out of water in the next 60 to 100 days. In a drought this badassed, it so far looks like most of California’s residents will be able to flush their toilets and brush their teeth for the foreseeable future.

OtPR, who is much smarter than I am about such things, thinks I’m being overly optimistic when I make this argument:

Oh no. There are about 4000 water districts in CA (if you count thirty-dwelling mutual water companies in the middle of nowhere). I’d bet a good third of them will be in a bad way this year. We’re just hearing from the earliest and direst ones.

So I’m probably saying something really dumb here. But having watched Texas go through this, and having covered and lived through New Mexico’s tough times last year, I’m going to boldly predict that most water providers will limp through to the finish line. In Texas, the national press repeatedly descended on Spicewood Beach to tell the story of drought because nobody else was actually out of water. People deal with this by using less water. Somewhere in the dangerous future, conservation may lead to demand hardening that will make this a much more difficult problem. But for now, there are a whole lot of you using more than 200 gallons of water per person per day. You’ve got plenty of room to move.

Years ago, the great Kelly Redmond offered this helpful definition of drought – “insufficient water to meet needs.” The key here is that needs can change, and this year, my beloved California, they are going to have to.

You can do this.