Acequias and infrastructural inversions: The Corrales Siphon pumps, April 2023

My friend Scot and I rode north on yesterday’s bike ride to see the Corrales Siphon pumps.

Built in the 1930s, the siphon for nearly a century carried water beneath the Rio Grande to irrigate a thousand acres of land on the west side of the river at the northern end of the Albuquerque metro area.

More than a year ago, the siphon broke. The details of its breaking are unimportant, it was of an age at which stuff breaks. (I am old and breaking, and was riding an e-bike. See “infrastructural inversion” below.) The important thing is the way that things, in breaking, force us to think about them. As I wrote some years ago, malfunction has a way of clarifying function.

In the absence of a working siphon, we have dropped temporary pumps into the river to keep the Corrales ditches flowing. They were loud and smelly diesel pumps last year, but we’ve run an electric line and installed electric pumps this year, and they were humming quietly yesterday as Scot and I reached the northen-most point on our ride.

The cost is right now somewhere around $2m, I think, which amounts to about $2,000 an acre to for the Corrales irrigators, and that has been, without question, treated as a collective responsibility. We’re not making them pay to keep their water flowing.

For now, “the collective”, the “we” in my description above, means Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District property taxpayers. We pay for all of this irrigation stuff with property tax money, we don’t charge the irrigators themselves very much for the water. We treat it as a broad collective good serving the valley as a whole, not a narrow one serving the irrigators alone.

In the long run, the collective cost of fixing the Corrales Siphon for good will cost a lot more, and “the collective” will likely be New Mexicans as a whole, with money from the state’s severance taxes, which we collect from natural resource extraction (oil and gas and stuff).

This raises all kinds of questions, which have been helpfully brought to light by the siphon’s failure.

A gift: “Infrastructual Inversion”

I had the great good fortune Thursday to be joined by the fascinating Nathan Mathias on a bike ride to my (current) favorite place. The intellectual intensity of the experience, the depth of the conversation, is illustrated by the fact that I have no picture. I did not think to take pictures. (Luckily Nathan took pictures, and also blogged it!)

It was a friend-of-a-friend thing, Nathan was in Albuquerque and our mutual friend Luis Villa, noting our common interests (“collective action stuff” is the best shorthand, also bicycling, but bicycling in a particular way), suggested the meetup.

The “particular way” of our shared approach to cycling is a style of thinking that comes from moving across the human and non-human landscape with curiosity. The shared interest in collective action is Nathan’s work on the interplay among digital power, algorithms, and community, which overlaps conceptually and strikingly with my Venn diagram of interests in collective action around shared natural resources.

As I was explaining the work Bob Berrens and I are doing in trying to unpack and think through the unthought about underpinnings of Albuquerque’s relationship as a community (or communities) with the Rio Grande over the last century, Nathan pointed me to “infrastructural inversion”, a tool introduced by Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star in their 1999 book Sorting Things Out. The “inversion” of their title “is a struggle against the tendency of infrastructure to disappear (except when breaking down).”

As we rode down the Rio Grande levee bike trail Thursday morning – “river” confined to a narrow-human-built channel to our right, neighorhood to our left with the riverside drain between us and the affluent homes of the village of Los Ranchos – my curiosity was in overdrive. I’ve ridden that trail a zillion times, but Nathan’s gift of a useful new idea was a gift of beginner’s mind as I began a fresh explanation of the story of this place.

A gift: “thick places”

Last month my friend Sara Portfield gave me a similar gift.

She was visiting for a water conference, and I spirited her away for an early breakfast in Los Ranchos and a ditch walk – not coincidentally, along the same confluence of ditches where Nathan and I ended up Thursday. Walking and talking Sara, a historian, said at one point “This is a thick place.” It is an idea, I learned with Sara’s help, rooted in anthropology and history, and like all cool theoretical frameworks (see “infrastructual inversion” above) I am no doubt using it recklessly, but I’m lazy and in a hurry.

“Thickness” involves places characterized by a blend of historical events, cultural traditions, and stories that convey meaning when overlain.

The ditches of Albuquerque’s valley floor are that. They are thick.

The inductive method

I’ve lived my life as a journalist, and even without a newspaper paycheck, there’s no stopping now. Journalism is a fundamentally inductive exercise, the collection of anecdotes. Here is 20-year-old John at a Walla Walla city council meeting, trying to figure out what that new parking ordinance does. At the county fair, trying to figure out where that cow came from. At the state penitentiary, trying to figure out what a state penitentiary is. In Pasadena City Hall wondering where the water comes from. (That quite literally is where my career as a water writer began, as a 20-something city hall beat reporter wondering where the water came from. I was doing infrastructural inversion before it was cool!)

Throughout this life, I have periodically stumbled on academic conceptual frameworks that provide a framework in which to fit the puzzle pieces I’ve been collecting. This often happens suddenly, as the life-changing few days after Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel prize in economics, when I began devouring her ideas and a whole bunch of my puzzle pieces suddenly snapped into place.

There’s a feedback loop here, because theory helps tell me where to look for the next round of anecdotes. I am invariably at my most productive at moments like that.

A gift: Max

Two-plus years ago, I asked my friend Scot, he of the long Sunday bike ride, what farmers were thinking back in the 1920s about the future of agriculture in the Albuquerque valley as the modern institutions of flood control, drainage, and irrigation were being created.

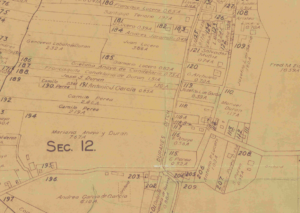

In answer, Scot found Max Gutierrez, whose name was largely lost to Albuquerque histories, but whose name kept coming up in old newspaper articles. Back in the day, Max was a big deal.

I am now in the midst of writing a book chapter about Max and the three ditches, the place I walked with Sara and bicycled with Nathan, and where Scot and I have ridden many times. It is a thick place, and thinking about it carefully allows a sort of infrastructural inversion that is shedding light on the Rio Grande, the community that Albuquerque has become, and what we might be in the future.

All of this is the product of the generous gifts of friends.