More than once last week while I was down in the Colorado River delta, I heard people involved with the historic “pulse flow” talk about one of the problems that comes next: managing expectations.

Fox Latino calls it a “flood”

This headline and file art, from Fox Latino, illustrates the problem. “Colorado River Begins Flooding Dried Up Delta,” the headline reads, accompanied by a picture of the Colorado River near Page, Arizona. The Colorado River I watched last week flowing past San Luis Río Colorado in Sonora, Mexico, was a beautiful thing to see, but it was another thing entirely from the stock imagery you see here.

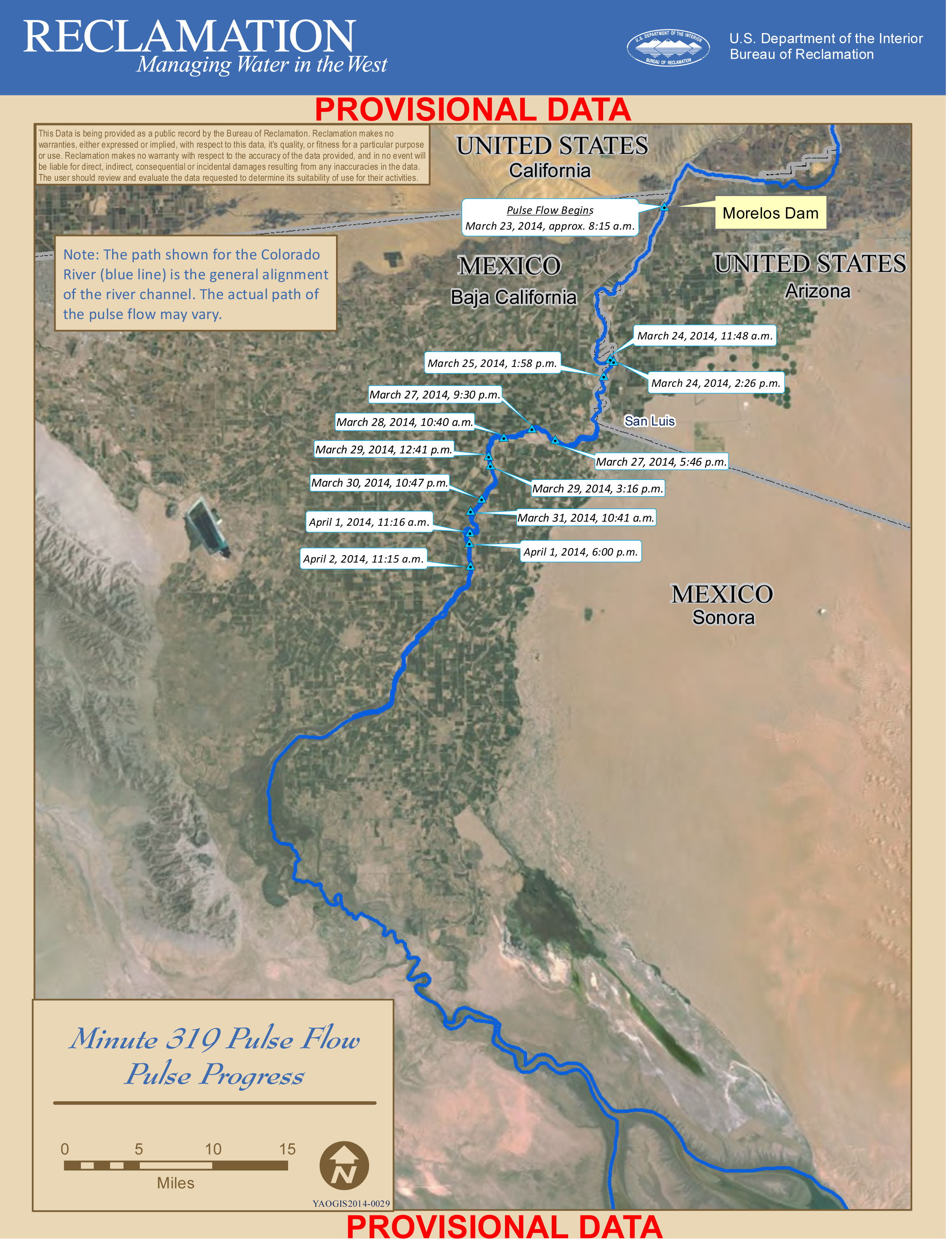

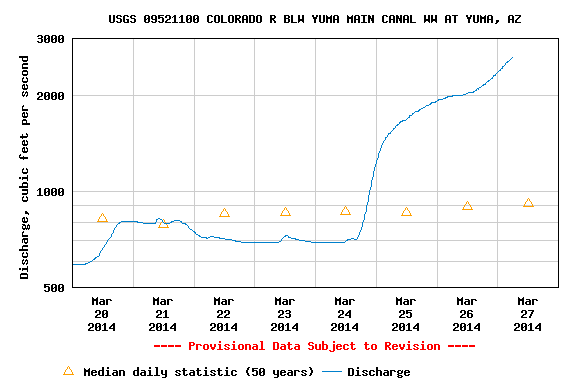

I don’t recognize where the picture accompanying the Fox Latino story was taken, but the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry (the nearest gage to Page) is running right now with a peak flow of around 10,000 cubic feet per second (a little less than 300 cubic meters per second). On Friday at San Luis, the last good number I had from a member of the U.S. Geological Survey team working on the pulse flow monitoring was around 1,300 cfs (37 cms). The releases from Morelos Dam, the place where water is being turned loose into the normally dry delta channels, are larger, but it’s a parched system, and the losses as the water headed downstream were significant.

USGS monitoring on the pulse flow, March 28, 2014, by John Fleck

In the desert landscape, it looked like a substantial river, as the picture to the left shows, but nothing like the “Mighty Colorado” imagery conjured up by a Fox Latino desk editor looking to fill a click-bait slide show.

In San Luis Río Colorado, the party was genuine, but it wasn’t clear how much the partiers understood how short-term this flowing river was going to be. That, at least, was the worry. I talked to four twenty-something men under the bridge in one of those broken Spanglish exchanges who clearly had little idea why the water was there or how long it would last, only that it was wonderful. “Thank you Americans!” one of them said. Our shared language wasn’t up to the task of communicating the fact that it was Mexican water, and the Mexican government and non-governmental organizations who were equally responsible for this shared project.

Here’s the thing. Wonderful as it is, the water is not going flow through San Luis for very long. The peak releases from Morelos Dam end today (Sunday, March 30). The releases will decline rapidly after that, with releases from Morelos into the main river channel ending completely by the third week of April, according to the USGS. It’s truly a “pulse” of relatively high water moving down the channel of relatively short duration, not a sustained simulation of a full spring flood flow. For the rest of April and into May, water for environmental flows will continue, but instead of being released into the main channel, the water will be moved through Canal Reforma and Canal Barrote, bypassing reaches of the river where infiltration losses were expected to be substantial because of deep water table.

Scientists and journalists tour Laguna Cori restoration site in the Mexican Colorado River Delta, which awaits its first flows. March 27, 2014, by John Fleck

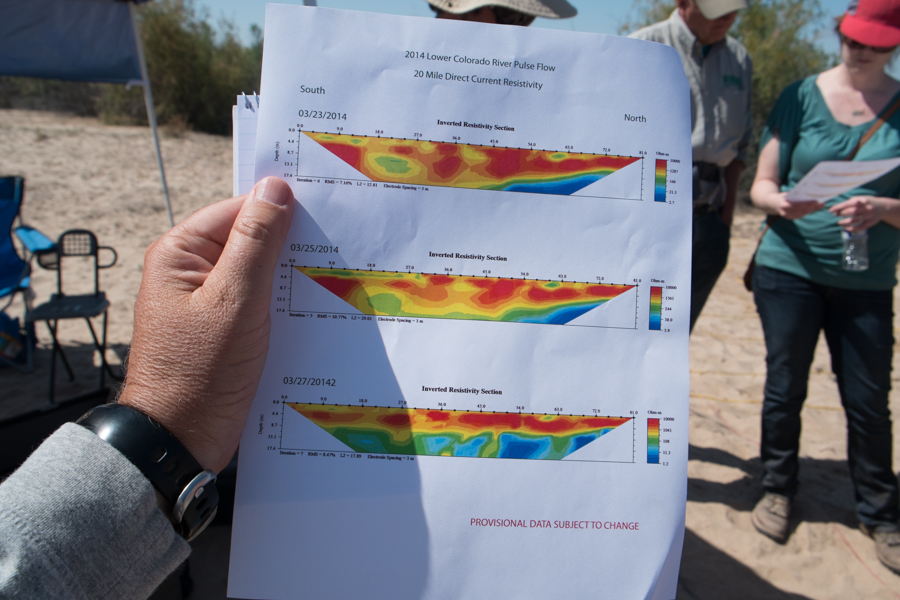

That will allow water to be targeted directly to key habitat restoration areas like this one at Laguna Cori, on the river’s western bank, which I toured with some members of the project science team and a group of reporters Thursday. (Huge thanks to Karl Flessa from the University of Arizona for shepherding around the delta.) Within the next couple of days, the scientists expect the main pulse released from Morelos, after having travelled down the main channel, to reach the key habitat restoration areas. The idea is a wetting from the channel to coincide with cottonwood germination. With the rapid recession in main channel flow, water then will be moved via more efficient irrigation canals to keep the site wet into May. This a site with a very shallow water table, which offers a much better chance for restoration. Properly nurtured, the scientists hope, the cottonwoods will be able to get their roots down into the water table, giving them a shot over the long run.

I admit to being as caught up as anyone in the “living river” part of this. Watching the water fill the dry, sandy Río Colorado bed at San Luis, watching the happy scientists and happy townsfolk splashing and partying was special. But if a “living river” is the goal, this is a very modest first step. Incredibly important, historic even, but modest.

Expectations are a funny thing.