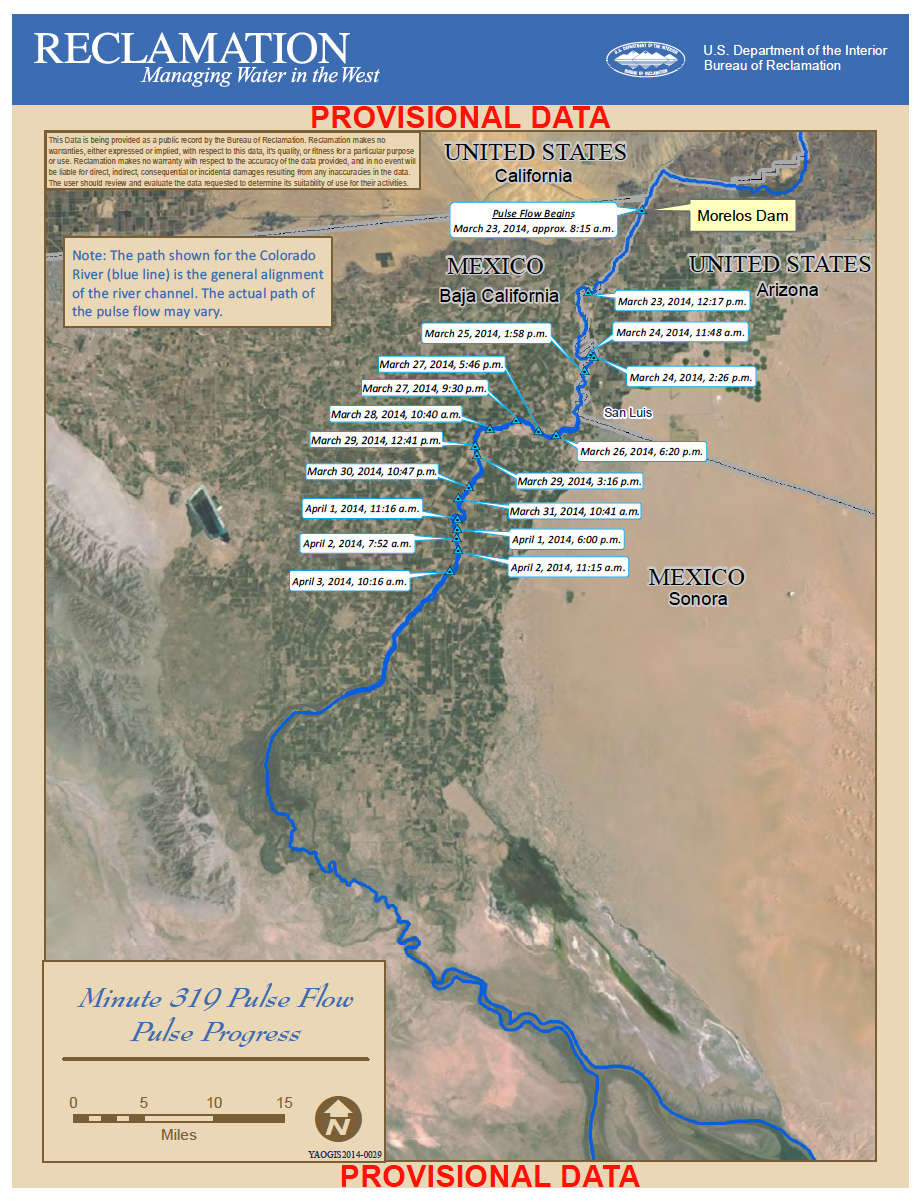

Colorado River pulse flow at the Laguna CILA environmental restoration site. Picture by Tomás Rivas of the Sonoran Institute, used with permission

Folks on the Colorado River delta “pulse flow” science monitoring team sent around a few pictures yesterday taken by the Sonoran Institute’s Tomás Rivas of the water arriving at the Laguna CILA environmental restoration site. The beauty of this picture for me, beyond the obvious sight of water in a formerly dry delta river channel, is that despite taking a site tour two weeks ago, I don’t recognize the spot where the picture was taken. Water changes everything. Here’s one of my pictures from our tour.

Scientists and journalists tour Laguna Cori restoration site in the Mexican Colorado River Delta, which awaits its first flows. March 27, 2014, by John Fleck

Imagine that now filled with water!

As I’ve written previously, Laguna CILA is one of the restoration sites that takes advantage of the high water table in stretches of the levee-pinned delta river channel to bring back native riparian vegetation. The idea here is that a pulse of “nature” in the form of water flows like this can help regenerate willows, cottonwoods and the like, which can then get their roots down into the water table and sustain themselves. Here’s how Jennifer Pitt of the Environmental Defense Fund and a group of colleagues explained it in back in 2000 (pdf), in one of the early academic papers explaining how it might work:

Annual flood events are not necessary for survival of these native tree species: they are capable of surviving at least a three-to-four-year interval between major flow events in the flood plain. Pulse flows of 260,000 acre-feet, released at a rate of 3,500-7,000 cubic-feet per second, are sufficient to inundate the Delta’s floodplain within the levees, sustain riparian corridor vegetation, and stimulate seed germination.

Much has changed since that was written. In 2000, the Colorado River’s reservoirs were mostly full, which made carving out a modest chunk of water to serve society’s environmental values seem more possible. The reservoirs are now half empty, which makes the political and policy challenge far greater. The flows in the current pulse are substantially less, but the water is now hitting sites that have been engineered to take better advantage of it.

This is fundamentally new territory. You drive across the farm fields of Mexicali and San Luis and see an agricultural technology that’s been optimized over a century to grow the most food and fiber with the least inputs. This thing that we’re seeing, in essence farming nature, is a new gig. Much study yet to come….