Disclosure: I digitally altered the original. The moon was moved.

The National Environmental Policy Act in western water

The National Environmental Policy Act – NEPA – is a weird bird. It’s one of the earliest of a suite of U.S. environmental laws that took shape in the 1960s and ’70s as environmental values grew into a substantive element of our nation’s politics.

It doesn’t actually protect anything, but it does require the U.S. government to analyze the environmental impacts of the actions it takes before it takes them. It’s a sort of “eyes open” statute:

The courts have always said that NEPA does not dictate results, only process, leaving agencies free to make environmentally harmful decisions.

That’s University of New Mexico law professor Reed Benson, who makes an intriguing argument for an expanded role for NEPA in western water management. Specifically, he thinks the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s current approach to NEPA implementation misses an opportunity.

The Bureau, which manages dams and water distribution in the western United States, unquestionably has significant environmental impacts. But the Bureau’s position (supported, apparently, by the courts) is that ongoing operations are not and should not be subject to environmental review under NEPA. Again, Benson:

The volume and timing of water storage and release affects water quality, recreation, fish and wildlife both above and below the dam. With these kinds of impacts, one might think that federal dam operations would be subject to environmental reviews under NEPA, just as federal land management activities are. But in fact, Reclamation rarely does NEPA reviews of “routine” dam operations, despite the serious impacts on downstream rivers.

Benson thinks that represents a missed opportunity:

NEPA reviews certainly will not resolve all the environmental problems associated with Reclamation’s dam operations. But I do think the NEPA process has value in the context of long-term operations plans, requiring the agency to generate alternatives, involve the public, and develop ways to mitigate impacts. In a West where the climate is changing, water uses are changing, and values are changing, I believe NEPA can help Reclamation make better decisions about the future of its projects.

If you’re interested in western water management, I recommend Reed’s full piece.

tossing out of the light

I’ve quoted before Don DeLillo’s great description of how, at a night baseball game, under the lights, “the players seem completely separate from the night around them.”

At our Albuquerque Isotopes’ home opener this evening, the players’ home whites seemed impossibly white, the grass seemed impossibly green, the sky behind the lights impossibly inky black. In the third inning, the left field lights went out, the players left the field, but to stay loose a couple came out and tossed, one in the light, the other in the shadows, not quite separate this time from the night around him.

I’ve always loved the way baseball usually draws your eye to the main thing – pitch, swing, hit, catch, throw – but then rewards the glance elsewhere, and when it gets complicated, the way you have to watch the outfielder sprinting for the fly ball while simultaneously watching the runners – are they holding? The third base coach is waving them in! Did the throw miss the cutoff man?

It was a pitcher’s game until it wasn’t, when the ‘Topes scored five in the eighth. A bases loaded triple that capped it was one of those “where do I look?” plays, a deep fly, an outfielder sprinting, baserunners on the move, a third base coach directing traffic (when in doubt, watch the third base coach). By then, some of the impossibly white jerseys were stained infield red, and the home team won.

Via Nature podcast, Alex Witze on the grand pulse flow experiment

If I’d done the geek stuff right, hit the play button below to hear a really nice piece by Alex Witze of Nature magazine from the Colorado River delta pulse flow. (I know, it’s a magazine, this is audio. Brave new world and all.) If I haven’t done the geek stuff right, you can probably also find it here.

And here’s a picture from the San Luis beach party you can hear at the end of Alex’s piece:

It now looks like 2017 is the earliest we could see a shortage declaration on the Colorado River

The latest Bureau of Reclamation monthly basin operating report, out today (the “24-month study”, pdf), makes it increasingly clear that we’re not going to see Lake Mead drop to levels that would require a shortage declaration in 2016.

The shortage is based on Lake Mead’s surface elevation, and the trigger level is 1,075 feet above sea level. According to the latest basin operating report, Lake Mead could drop below 1,075 in the spring of 2015. So wouldn’t that trigger a shortage declaration as early as the following year, 2016, then? No. This is where the specific language of the operating rules (pdf) becomes important. The formal decision about the shortage criteria is not made until the fall, based on most likely elevation estimates of the Jan. 1 Lake Mead elevation:

In the development of the AOP, the Secretary shall use the August 24-Month Study projections for the following January 1 system storage and reservoir water surface elevations to determine the Lake Mead operation for the following Calendar Year as described in this Section 2.

Lake Mead’s currently at 1,099, and unless space aliens come down and scoop up a bunch of water we’re unlikely to see a forecast of 1,075 by the time the August 24-month rolls around. That means it’s a virtual certainty we won’t have a shortage declaration for 2015. We’re likely to see 1,075 by the spring of 2015, but as long as the August forecast shows it bouncing back by the following Jan. 1, no shortage for 2016 either. Which the latest 24-month study suggests it’s likely to do.

But as Juliet McKenna notes, odds are good (bad?) for a shortage as early as the 2017 calendar year:

This year, runoff from the Upper Basin is projected to be slightly above normal, minimizing the chance of shortage declaration in 2015 or 2016. However, for 2017, the chance still exceeds 50 percent. The past 30 years remain the driest such span on record and, with storage currently below 50 percent of total reservoir capacity, the chances for shortage become even higher after 2017.

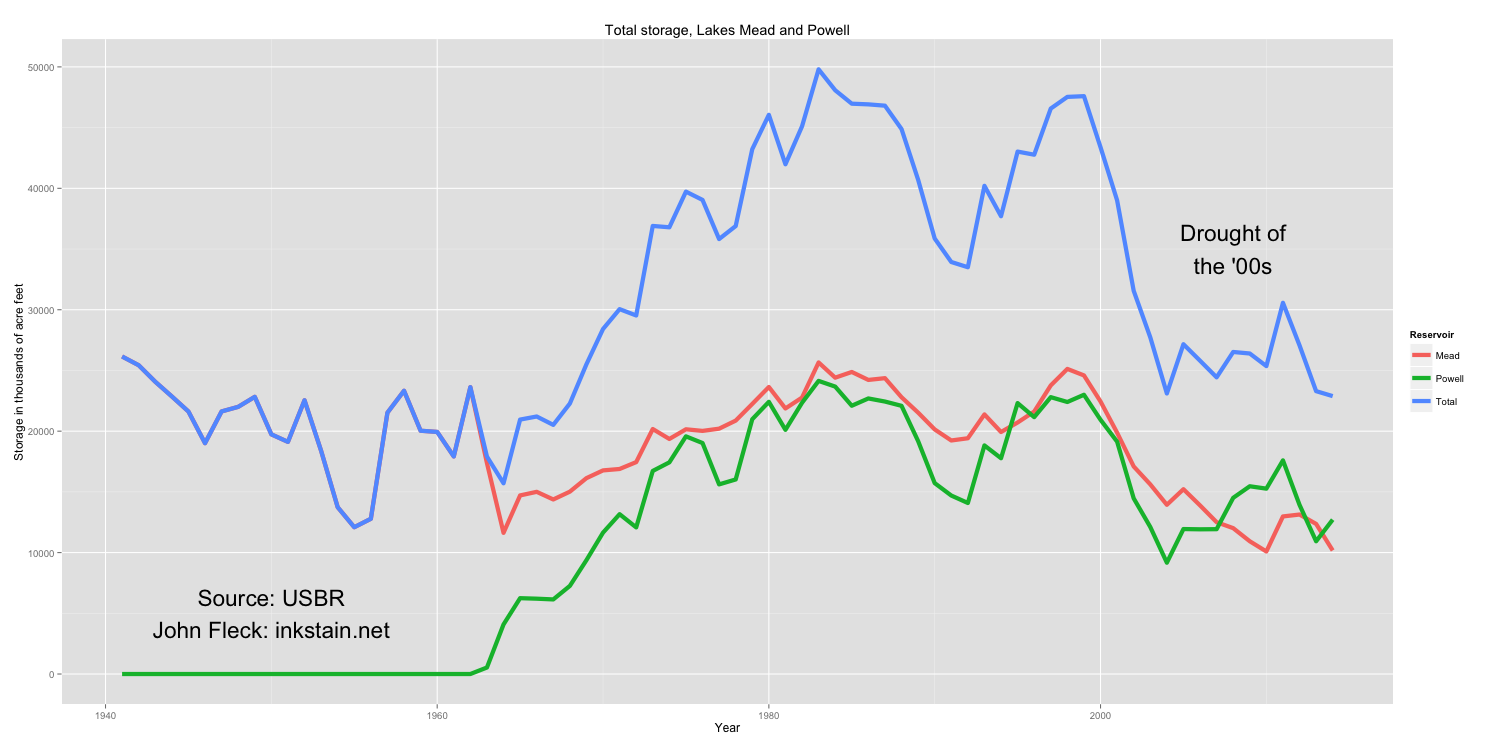

Here’s the updated graph with estimated Mead and Powell reservoir storage through the end of September:

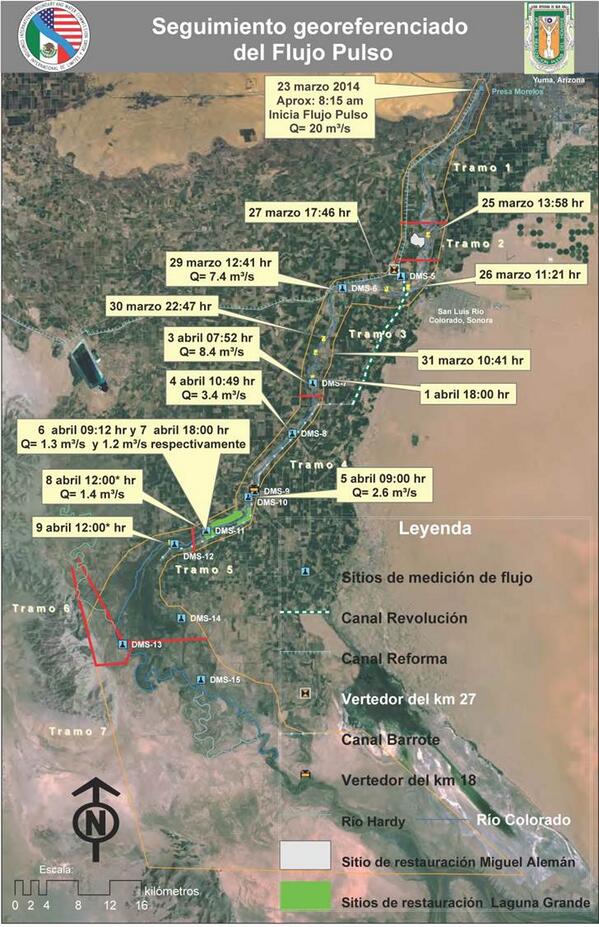

pulse flow progress

In Las Vegas, an acknowledgment that growth is gone

You can’t understand water in the west without understanding urban growth patterns. They’re joined at the hip. Here, in a single graph, is the explanation for the Vegas announcement yesterday that its two main water agencies are laying off 7.5 percent of their staff:

Henry Brean explained it thus:

The Southern Nevada Water Authority and the Las Vegas Valley Water District began laying off 101 full-time workers Wednesday as the wholesale water supplier and its largest member utility shift their focus from chasing growth to maintaining existing infrastructure.

“At both the district and the authority for the last 20 years or more, we worked to install the plumbing that makes big parts of our community possible,” said John Entsminger, general manager of both agencies.

Today that mission has changed from “growth-support” to one focused on operations, maintenance and customer service, he said.

The Colorado River is no one thing

Photographer John Trotter on the Colorado River:

When they opened those gates on (Morelos) dam and let water back into the main channel on the river, it kind of engaged those people. It brought them back into the mainstream of all the other people who are living along it in Moab or Grand Junction or Needles or Tucson. All these people are party to this very over-allocated river.

I came to realize that people, especially here in the East, they don’t even know that it’s the same river that I’m talking about. That the one going through the Grand Canyon is the same one that goes to the Delta in Mexico.

I encourage you to click through to High Country News to see Trotter’s pictures of the river, the pulse flow, and the delta.

fighting off the desert with fake water

Meadow Lake

We come to a desert but it is not to our liking. One wonders why, then, we came to a desert, but no matter. We can engineer our way out of this:

Meadow Lake was never much of a meadow. It was too wild, too wide, its sage-studded plains golden with buffalo grass and endless sunshine spilling, sparkling toward the blue shadows of the Manzano Mountains to the east.

But there had been a lake.

In 1967, the lake – fed by eight wells and stocked with trout, bluegill and catfish – had been the focal point of a 1,700-acre community planned by Albuquerque developer D.W. Falls.

That’s my colleague Joline Gutierrez Krueger in a sad piece about the ambitions of land development on the greater Albuquerque metro area’s south side. Journal photographer Dean Hanson added some nice ruin porn of the gutted mobile homes that are, along with crime, now Meadow Lake’s hallmark. And no lake.

As so often is the case, we learn late that can’t engineer our way out of this.

Welcome, pulse flow readers. Buy my (old) book!

It occurs to me that the brief and delightful pulse flow of clicks to this blog reading my recent coverage of what’s going on in the Colorado River delta might be potential book buyers. (Duh. Marketing is not my strength.)

It’s called The Tree Rings’ Tale, a science book for kids (middle school aged, 13 years old give or take) about weather, water and climate, especially here in western North America. Yes, it has John Wesley Powell’s grand adventures, and also Connie Woodhouse’s more recent grand adventures. (Connie uses tree rings to figure out how much water was in the Colorado River back before we had stream gauges. She’s not as famous as John Wesley Powell, but her stories are pretty great and important too.)

It includes a lot of hands-on science, too, like how to record the rain and snow in your backyard.

If you buy it on Amazon via the link above, I get a little piece of the action, which is nice, but if there’s some bright youngster in your life who you think my enjoy it, the best thing would be to support your local bookstore and order it through them.