In Sacramento, you no longer need fear getting a citation for letting your lawn go brown. What’s next – water meters?

Whose river is the Colorado?

When I set up a Google News alert some years ago on the words “Colorado River”, I noticed a revealing pattern. In spring, as the weather warmed, the water management and drought news I was hoping for was increasingly mixed with stories of drunk people drowning in the river. In the fall the mix of drunks and other ill-advised recreationists tapered off.

When I was a kid growing up in the upper middle class suburbs of LA in the 1960s and ’70s, friends would take off in their campers, towing boats, for a weekend at “the river”. In his epic book A River No More, Philip Fradkin describes the “Parker Strip”, the stretch between Parker and Headgate dams on the Arizona-California border:

It is the river as theater, where each of the 125,000 weekend visitors compressed into the fourteen miles, and huddled as close as possible to the cool water, can act. To be a protagonist, rather than part of the supporting cast, one needs a sleek water-ski boat in the shape of a tapered arrowhead and powered by a jumble of chrome.

There was beer – “a million cans … can be consumed in one long holiday weekend” – and the throbbing of a disco beat at waterside taverns. “The Colorado is a charnel river at this point,” Fradkin wrote.

He tells the sad story of attempting a kayak trip with a friend from a place called Walter’s Camp, south of Blythe on the Lower Colorado, midway between the Parker Strip and the river’s end at Morelos Dam. Their attempt at a quiet paddle through exquisite desert (I know this, having paddled that stretch myself) was ruined by some three hundred motorboats in the Blythe Boat Club’s annual river regatta. It’s easy to feel sympathy for Fradkin and his friend when a water skier zooms close and sends a sheet of river water over the kayaking pair. But implicit in his argument is something that’s problematic in negotiating the terrain of Colorado River management in the 21st century.

Fradkin calls the Parker Strip “a charnel river” – a death house. But his description of the pulsing humanity is anything but. It’s alive, just with people doing things of which Fradkin disapproves. 125,000 people with their RV’s and motorboats and beer were embracing the river, just with a different set of values than Fradkin’s. This is a hard problem, because there is no a priori value for the Colorado or any river, but we get tangled up in groups who hold each set of values assuming theirs is the right one. We want it as a water supply for our farms and cities, and as a haven for motorboats, and as a place for a quiet kayak, and as a living river that is its own intrinsic value separate from the way humans might choose to use it. There’s conflict among those values, because we can’t have them all simultaneously, and Fradkin is pissy because his values have long been on the losing side.

As a child of the Sierra Club who paddled the river rather than motorboated as a youngster, my cultural sympathies long aligned with Fradkin’s. But here’s the thing I think he gets wrong. When I was a teenager, my Boy Scout troop canoed the same stretch of the river, past Walter’s Camp. It was 1973, around the same time as Fradkin’s ill-fated voyage. It was a quiet delight. But I understand now that the “river” we rode wasn’t really a river at all, but rather a water supply delivery system using the old river’s channel. The “thin veil of vegetation” along the riverside that Fradkin celebrates as he describes the river’s beauty there is really a vestige of the river’s management – what was left to grow after the spring floods were cut down by Hoover Dam to the north. It’s lovely, but ecologically and environmentally, it’s a mess. It’s not a river in any Platonic sense, but rather a human construct. Fradkin simply prefers his construct to theirs.

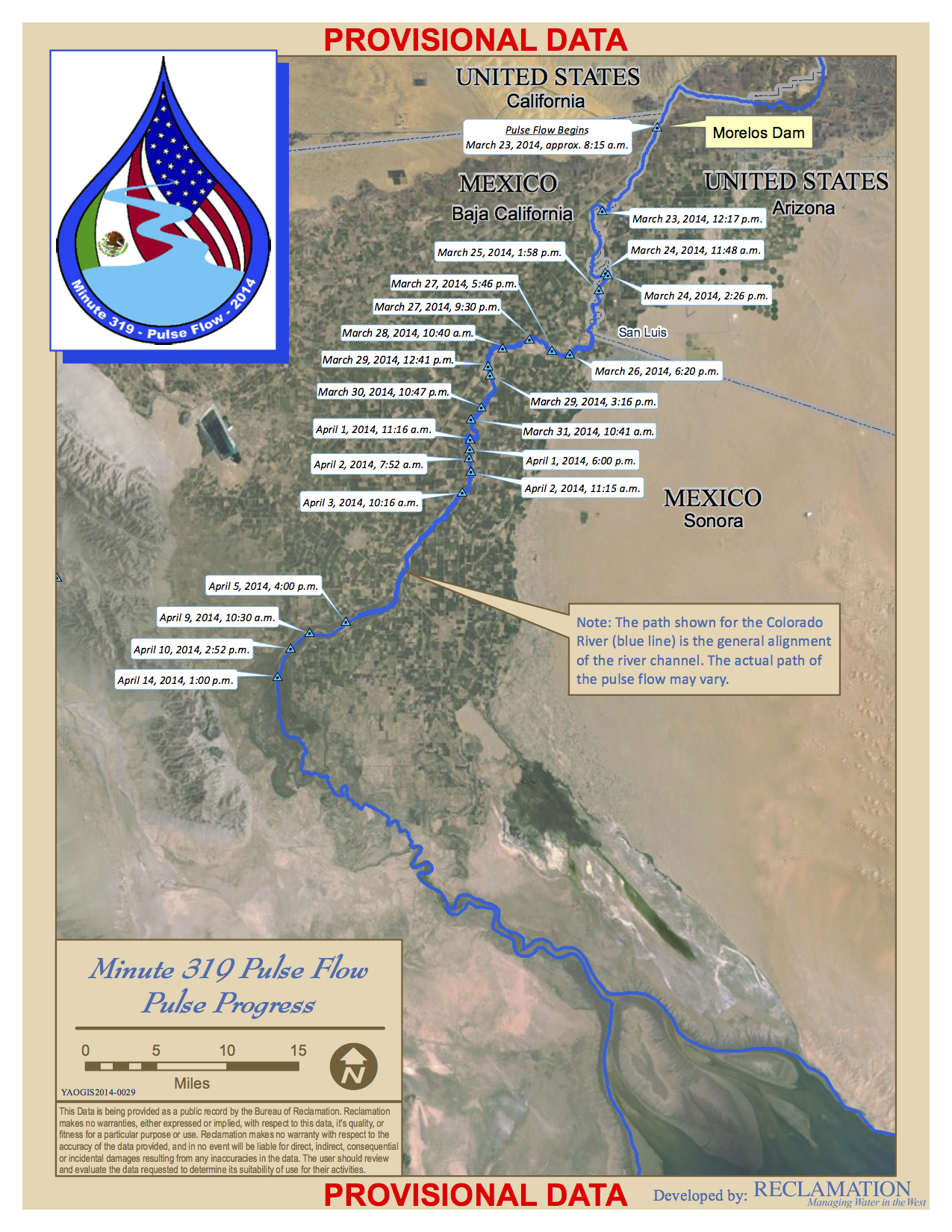

I took Fradkin along as my trip book last month when I went down to the delta to cover the release of the environmental pulse flow from Morelos Dam. The reason I’m so interested in the pulse flow experiment is because of the way Minute 319, the international agreement that made it possible, attempts to find some sort of common ground spanning the different value systems we have for the river. The deal has a complex mix of farm water and urban water and water for the environment, and nobody got all of what they wanted but the deal recognizes that no one set of values is right, and no one interest group can simply muscle its way to the front of the line.

And then at San Luis Río Colorado, as the border community saw substantial water flow through the usually dry river for which their town is named, I saw a remarkable spontaneous party emerge. There were environmentalists from the United States and Mexico, and scientists, and bureaucrats from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and townsfolk drinking beer and tearing up and down the river’s edge in their four-wheelers. And everybody seemed happy to share the river. There was no one right way.

Do Not Spray

Pulse flow slows

Postel on watching a river’s return

The first fingers of the Colorado Delta “pulse flow” creeping toward San Luis, March 25, 2014, by John Fleck

Sandra Postel on the experience of watching water return to the Colorado’s sandy delta bed, again and again:

For me, some of the most powerful experiences have come from visiting the same location twice – before the river got there, and then again after its arrival.

One morning, we visited a dry, sun-baked, sand-filled channel that, more than anything else, evoked sorrow and loss. My main memory of that first stop at Reach 3 was of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California hydrology team’s pick-up truck getting stuck in the deep channel sands that the Colorado River had delivered there many years ago.

When we returned to the same spot a few days later, the river was running through it – and the landscape had been completely transformed.

We arrived at sunset, and the beauty was breathtaking. Could this possibly be the same place where the truck had gotten trapped? Why had we not brought a picnic dinner to enjoy by the river’s bank?

Mulroy joining Brookings

To Colorado Basin water nerds’ favorite question – What’s Pat up to? – we have an answer.

According to the Las Vegas Sun, former Las Vegas water czar Pat Mulroy is joining the Brookings Mountain West project:

Robert Lang, director of Brookings Mountain West, said the shrinking Colorado River is one of the most critical issues facing the Western U.S., as it threatens the water supply to Las Vegas and dozens of other cities.

Without a stable supply of water, large portions of the country’s economy, including much of its agricultural sector, would be threatened, with future growth in the region crippled.

Brookings Mountain West began fundraising to hire a water expert before it knew Mulroy was available as part of a plan to direct more resources to studying water issues. When Mulroy announced she was retiring, she immediately became a perfect fit for the job, Lang said.

“She seemed like the most qualified person in the country to hire,” he said.

Mountain West is a partnership between the Brookings Institution and the University of Nevada Las Vegas, with a focus on the future economy of the intermountain west region. (Here’s a piece I did on some of their work back in 2008.)

In addition to the Brookings-UNLV project, Mulroy will be affiliated with the Desert Research Insitute in Reno, according to the Sun.

Alvarado Dr., Holbrook, Ariz.

This isn’t just old west ruin porn. There’s actually a water policy question here. This is in Holbrook, Ariz. There’s a big, expensive new levee protecting this neighborhood from the Little Colorado River. These properties back onto the levee. How do they decide whose property warrants protection?

A weird dry stretch

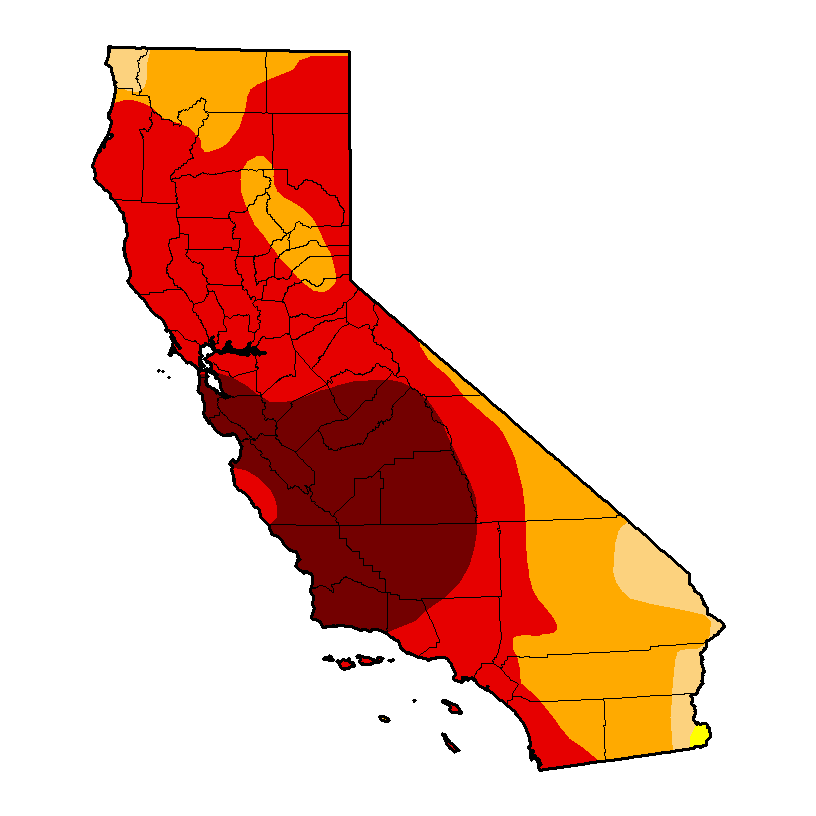

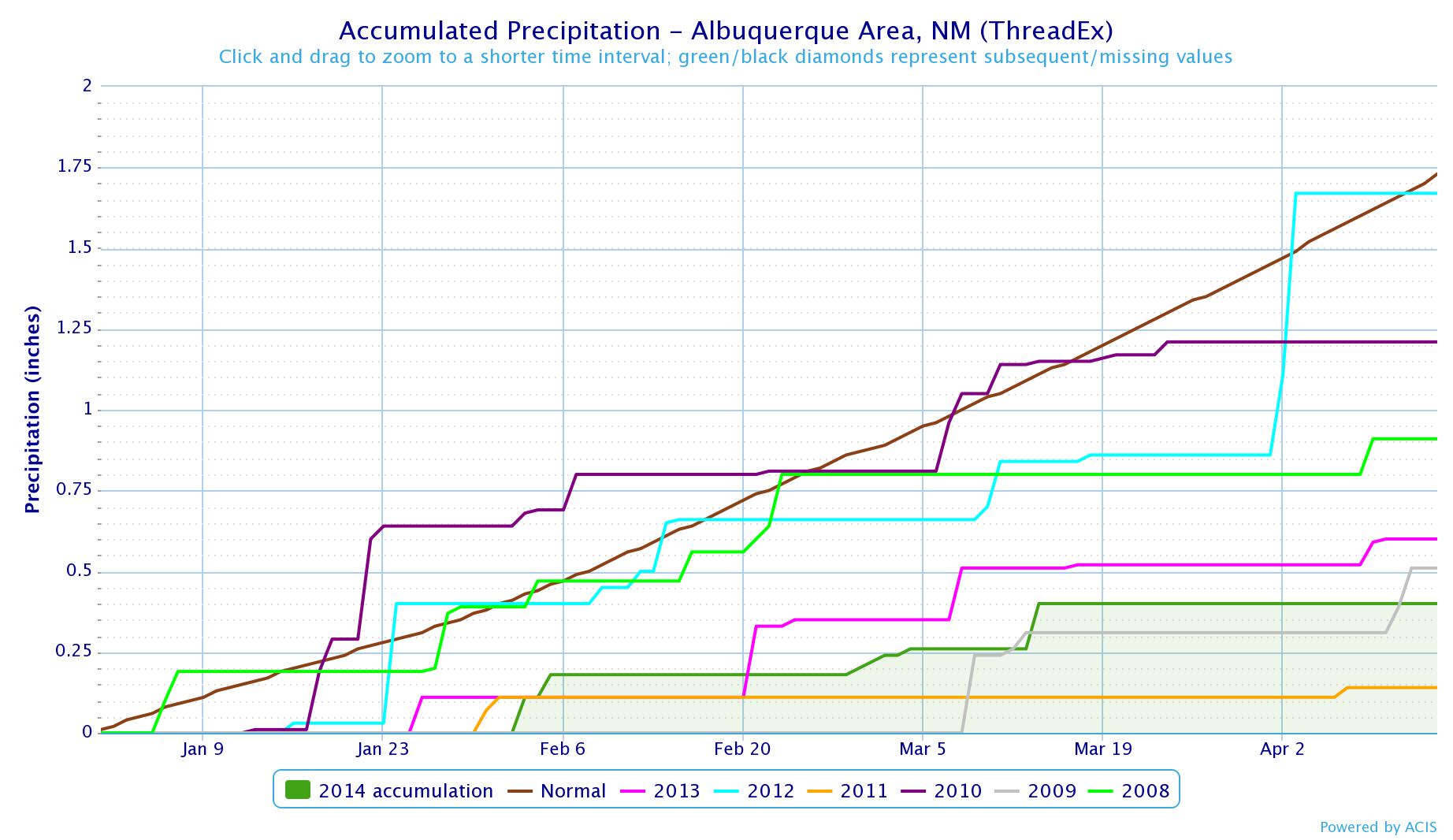

Here’s a statistical oddity. Through April 14, we’ve measured 0.4 inches (10 mm) of precipitation at the National Weather Service’s Albuquerque gauge in 2014, about 23 percent of the long term mean. This is the seventh straight year that Albuquerque has been below average through April 14. 2007 is the last calendar year in Albuquerque that got off to a wet start:

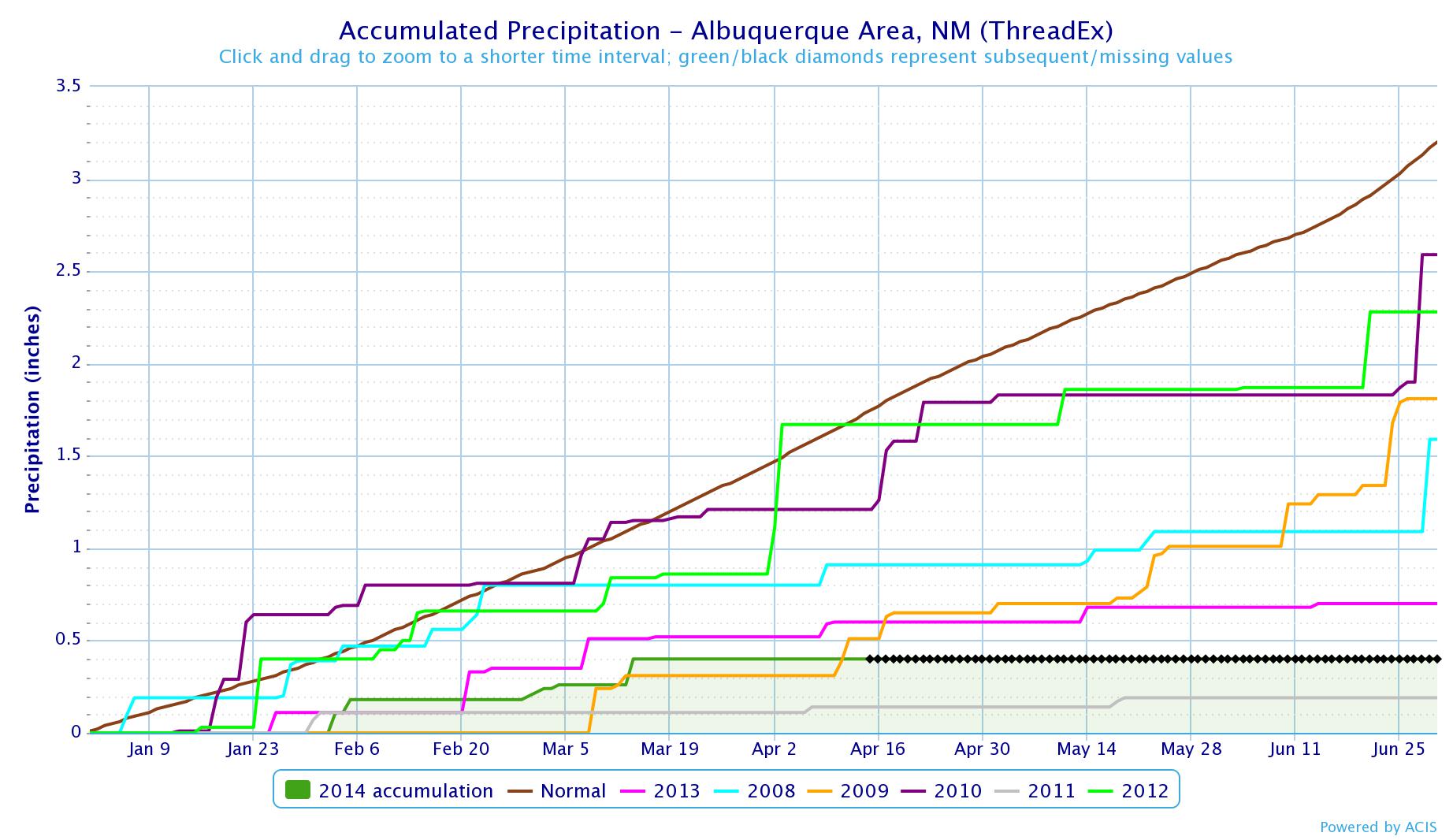

There’s nothing special about April 14 other than the fact that today’s the day I happened to write this blog post (I’ve been watching this phenomenon for weeks). In fact, if you plot things out to the end of June, we’re on track to have the seventh consecutive year that the first six months of the calendar year were drier than average (the line of little black boxes is this year – the black box indicates days for which we do not have data):

Here’s hoping we break the string.

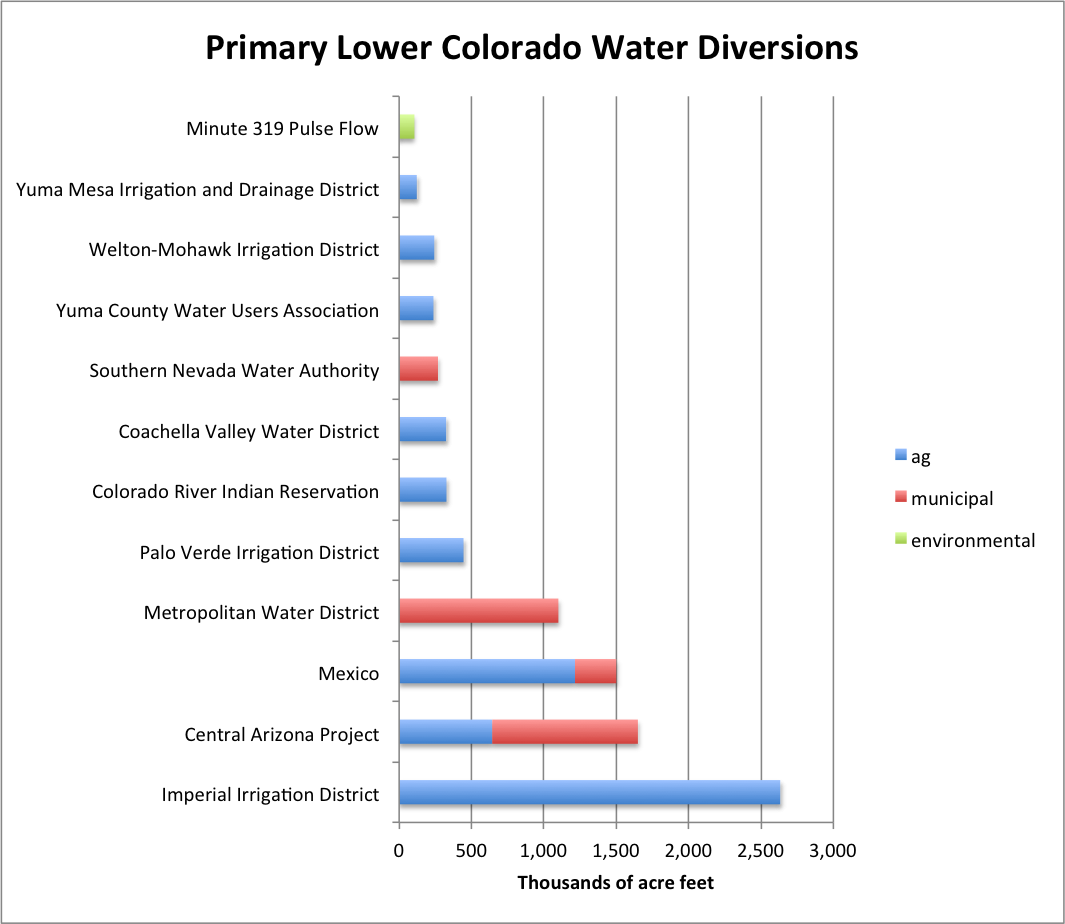

AMACRQ: Colorado River Use Bar Graph

A couple of weeks back, I made a quickie bar graph to provide some context for the amount of water involved in the Colorado River Delta pulse flow. It was half-assed. A reader asked for more: “Would love it more if it included other things, like Las Vegas consumption, MWD consumption, UB pasture irrigation, and so on…. Nothing like a bar graph to put things in perspective.”

In response, today we launch a new feature here on Inkstain: Ask Me A Colorado River Question.

The main point here is that the environmental pulse flow, as significant as it is, involves a relatively small amount of water.

As you can see, I didn’t go quite as far as my reader asked. This is only Lower Colorado River Basin diversions – Lake Mead on down. Other notes on the data:

- It’s only diversions greater than 100,000 acre feet. That captures 97 percent of the water use, and made typing in data a lot easer.

- 100,000 acre feet ~ 123 million cubic meters in the rest of the world, apologies for our wacky US water measures

- For the Central Arizona Project, I estimated the ag-urban split based on data here and the presumption that all the Indian water was M&I. That’s probably wrong, so the ag-urban split is probably wrong, but the overall bar size is what matters.

- For the Mexico numbers, I presumed 81 percent of the water diverted is agricultural, which is a commonly used number, but I haven’t chased down its origin yet.

- The numbers came from the USBR’s 2013 consumptive use report (pdf here)

- My spreadsheet with the numbers is here

Margaret Bowman on the Colorado Basin solution space

From an interesting talk last month by Margaret Bowman on a vision of what the Colorado River Basin solution space might look like (pdf of talk text here):

[T]he region’s agricultural industry will be modernized with more efficient irrigation technologies. This modernization will not only increase the productivity of agriculture, but will also result in a surplus of water that farmers can voluntarily sell or lease to cities and for river flows.

… [C]ities manage their water supplies smartly, with improved efficiency and recycling technologies. Residents transform their landscaping to look like the beautiful arid western landscape where they reside, rather than eastern green grass communities. With these changes, cities are resilient to unpredictable weather, and not rendered bankrupt due to expensive and environmentally damaging Rube Goldberg plans to pipe water in from faraway lands.

… [T]he iconic rivers of the basin remain healthy and resilient. As a result, the region’s $26 billon recreation and tourism industry continues to grow, and residents looking for a high quality of life are attracted to the region to work. Fish and wildlife are healthy, and as a result the region is not subjected to divisive and expensive endangered species act fights.

And finally … federal and state agencies, water utilities, farmers and ranchers, tribes and conservationists all work together to adapt our system of managing water so that energy can be spent on sharing water most effectively rather than litigating old disputes. With this more fluid market for sharing water (pardon the pun), private capital is attracted into investing in the region’s water solutions. Added to federal and state funding, these private investments can finance the infrastructure improvements needed to effectuate these changes.

The talk’s about 15 minutes and is worth a listen: