Kids on the Mexican side of the border, waving at delegation of Americans, San Luis Rio Colorado, March 28, 2014

This is my favorite border picture from my trip last month to Arizona-California-Sonora-Baja.

You can see the old border fence on the right, one of those repurposed metal landing strip things, which as near as I can tell is where the actual border is. The big new fence is pulled back 50 yards or so from the real border, just out of the picture to the left, creating a no-man’s land in between where this magical invisible line separates those adorable preppy Mexican kids from me and the group of U.S. water managers I was tagging along with. We were all there to see the same thing (water flowing down the Colorado River, just out of the picture to the right) and we were all happy and smiling and loving it, but there was this invisible line between us.

I’ve been wanting to write about border issues, because they’re fascinating, but feeling a little sheepish because I’m such a newbie. Most of my energy in reporting on Minute 319 and the Colorado River environmental pulse flow has been focused on the Byzantine transboundary water law and policy questions, but there’s this whole other set of cultural issues associated with that invisible line, which I’m far from understanding, that are fascinating.

In the latest issue of Boom, Michael Dear writes about the feedback between lives on both sides that makes the borderlands uniquely separate, on either side, from their respective nations:

The communities along the line are far distant from the centers of political power in the nations’ capitals. They are staunchly independent and composed of many cultures with hybrid loyalties….

Mutual interdependence has always been the hallmark of cross-border lives. After the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo settled the Mexican-American War, a series of binational “twin towns” sprang up along the line, developing identities that are sufficiently distinct as to warrant the collective title of a “third nation,” snugly slotted in the space between the two host countries.

Dear calls the western third of the U.S.-Mexican borderlands “Bajalta California”. William Vollman is talking about something different but conceptually overlapping when he draws the Imperial Valley in the United States and the Mexicali Valley in Mexico together into a region he calls simply “Imperial “, and then writes about with reckless abandon. For Vollman, it is all of a place, with “Northside” and “Southside” distinguishing location relative to the imaginary line. These kids, I think, live in Bajalta, or Southside Imperial, or both.

“, and then writes about with reckless abandon. For Vollman, it is all of a place, with “Northside” and “Southside” distinguishing location relative to the imaginary line. These kids, I think, live in Bajalta, or Southside Imperial, or both.

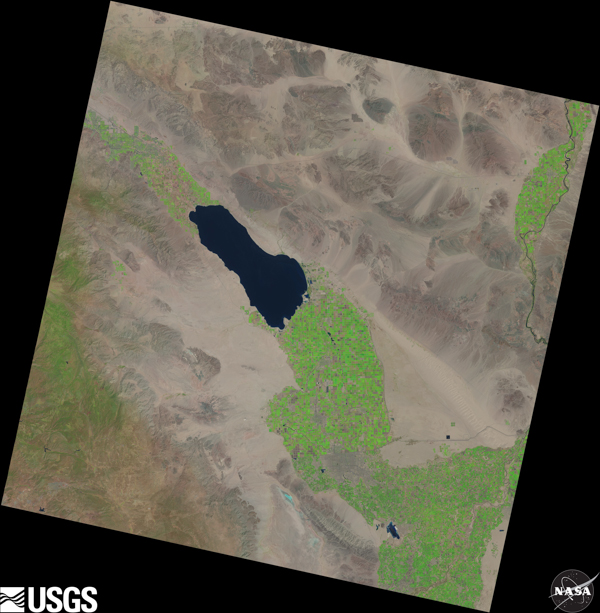

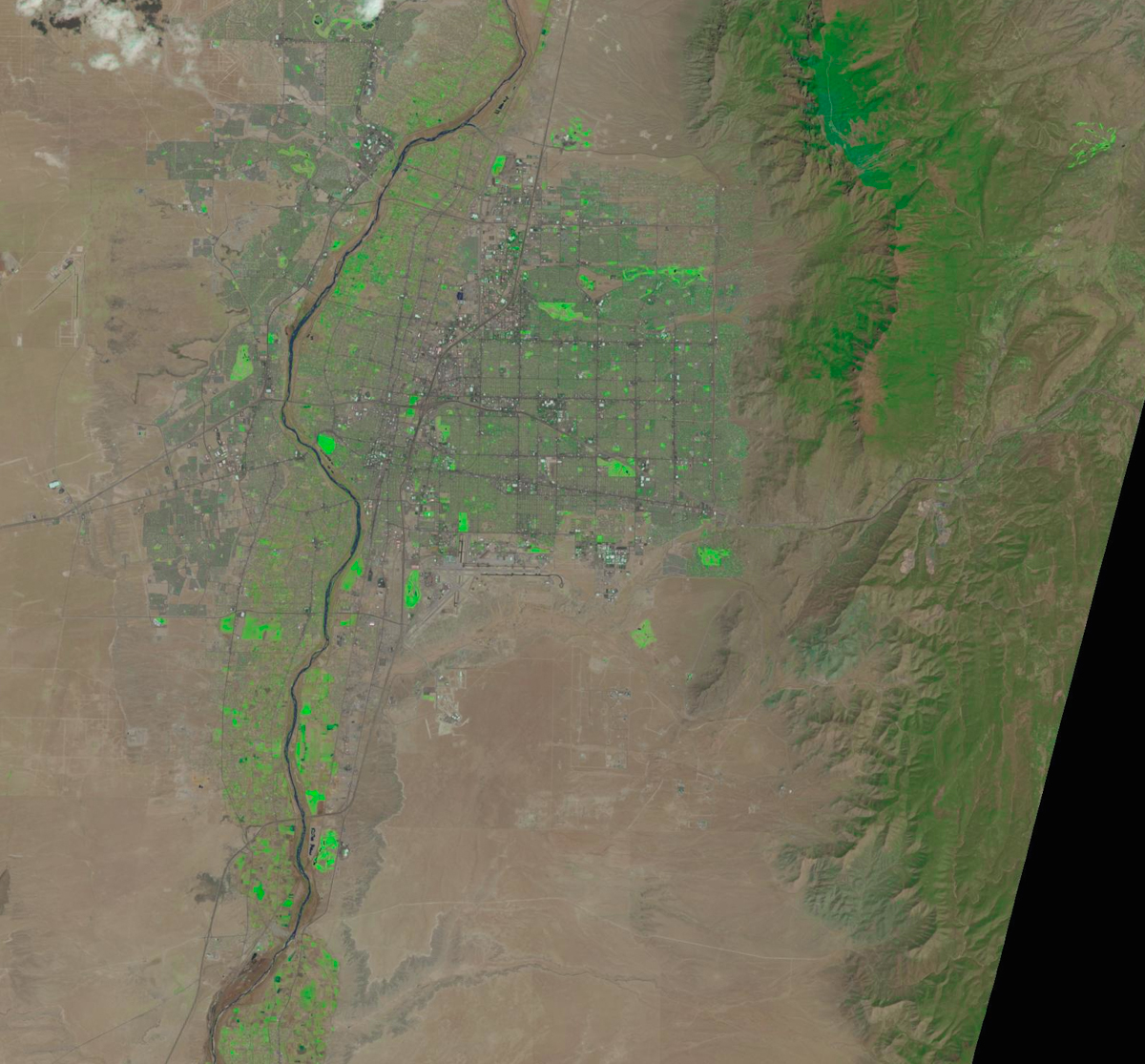

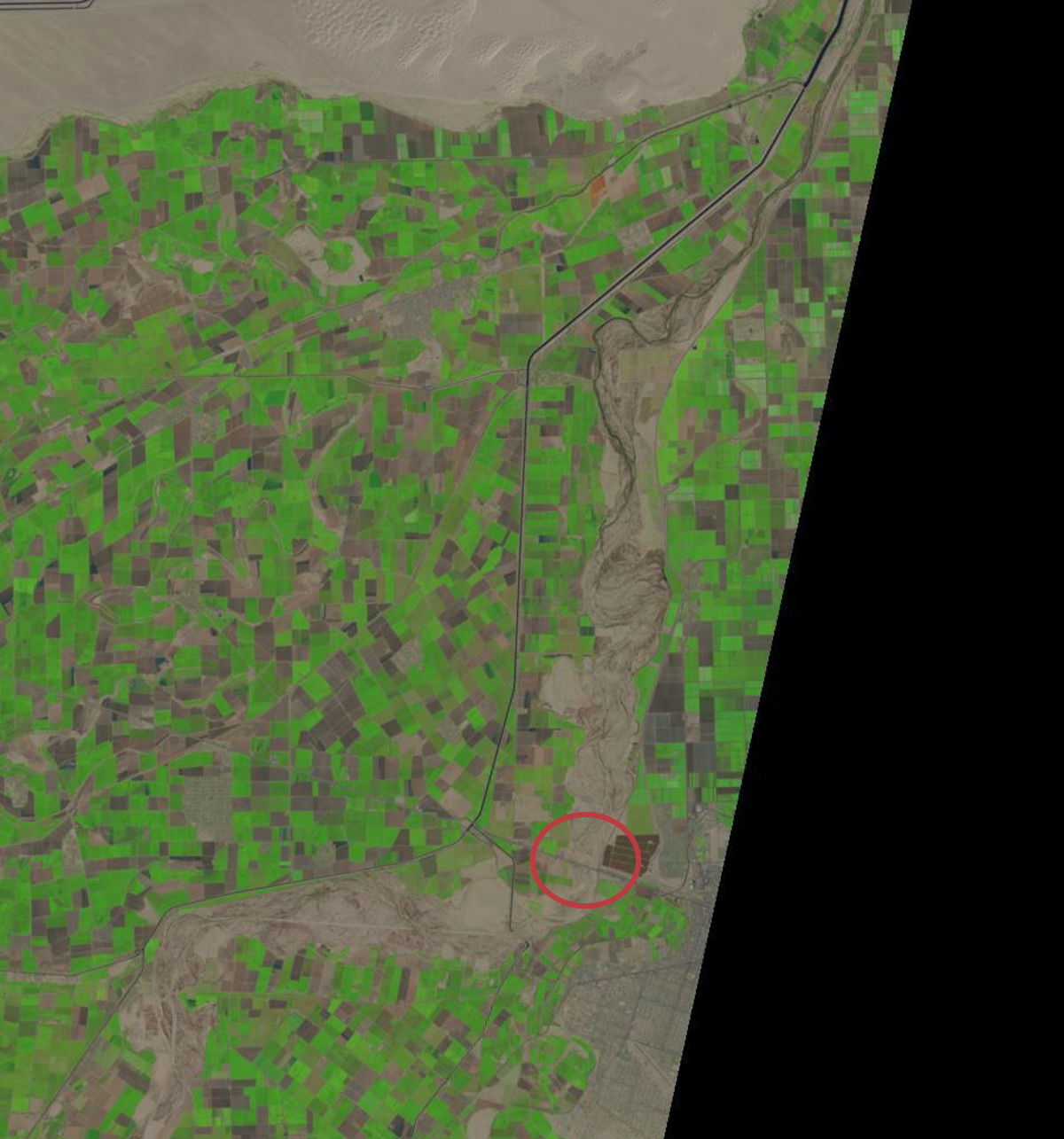

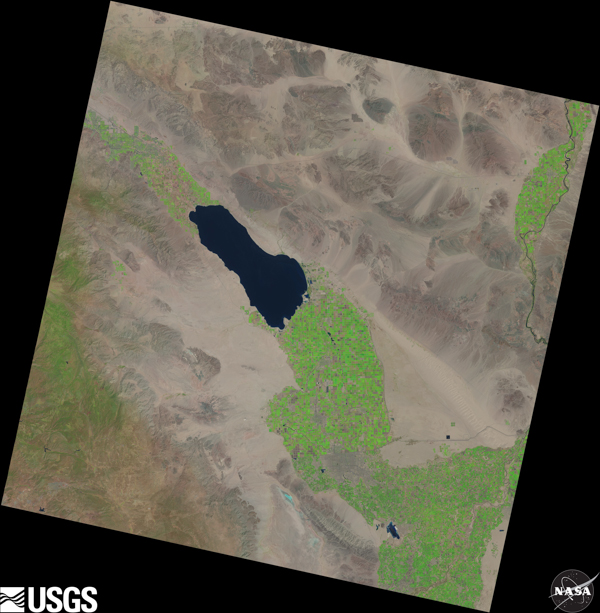

The grass does seem greener on the U.S. side of the border in this NASA Landsat image, but Imperial and Mexicali are clearly one valley

It is impossible to understand the water piece of this story without understanding the borderness of the region – the way U.S. landowners led by Harrison Gray Otis, the publisher of the Los Angeles Times, became the largest landowners in the Mexicali Valley, and the interplay of water power politics across the imaginary line. It is impossible to understand the 21st century extension of the story without understanding the way the U.S. Endangered Species Act failed to protect critters in Mexico when the Colorado River delta was dried up, largely by human water use on the U.S. side of the border. But at least I know how to approach the problem of making sense of those historical, legal and policy questions.

Making sense of the human dimension of borderness is another thing entirely. Earlier in my week in Bajalta, I’d come up to this same spot the above picture was taken, with a helpful Border Patrol agent as tour guide. There was a Mexican family standing right about the same spot as the kids in this picture, parents and a little kid who had come out to see the water. The Border Patrol guy went up to talk to them, and they exchanged pleasantries, each on their respective sides of the invisible line. They all knew right where the line was and what it meant. It’s going to take a little more time to make sense of that.