An Inkstain guest post from Jack Schmidt, crossposted with encouragement from the Utah State University Center for Colorado River Studies

By Jack Schmidt | December 7, 2023

In Summary

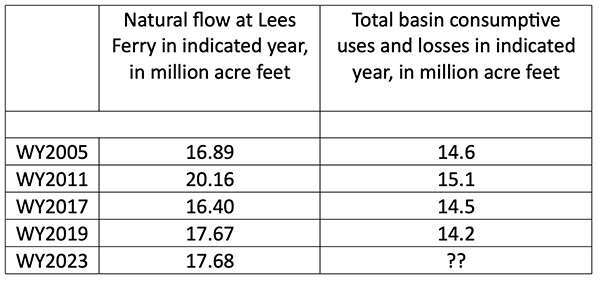

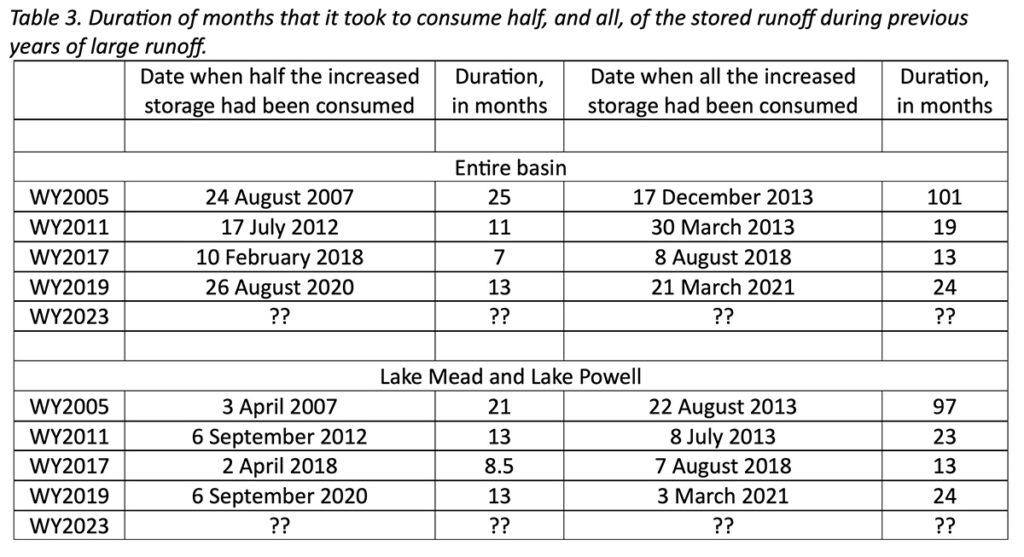

By the end of November 2023, storage in the reservoirs of the Colorado River watershed had been reduced 1.73 million acre feet from the high of mid-July. We’ve used 21% of the gains from the exceptional 2023 runoff, a drawdown slower in the annual cycle than in it has been in all but one year of the previous decade. New policies to reduce basin-wide consumptive use may be working. To date, about one-third of losses were from Lake Powell and Lake Mead, one third from CRSP reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell, and one-third from other Upper Basin reservoirs. Losses in the combined storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead specifically have been much less than in previous years.

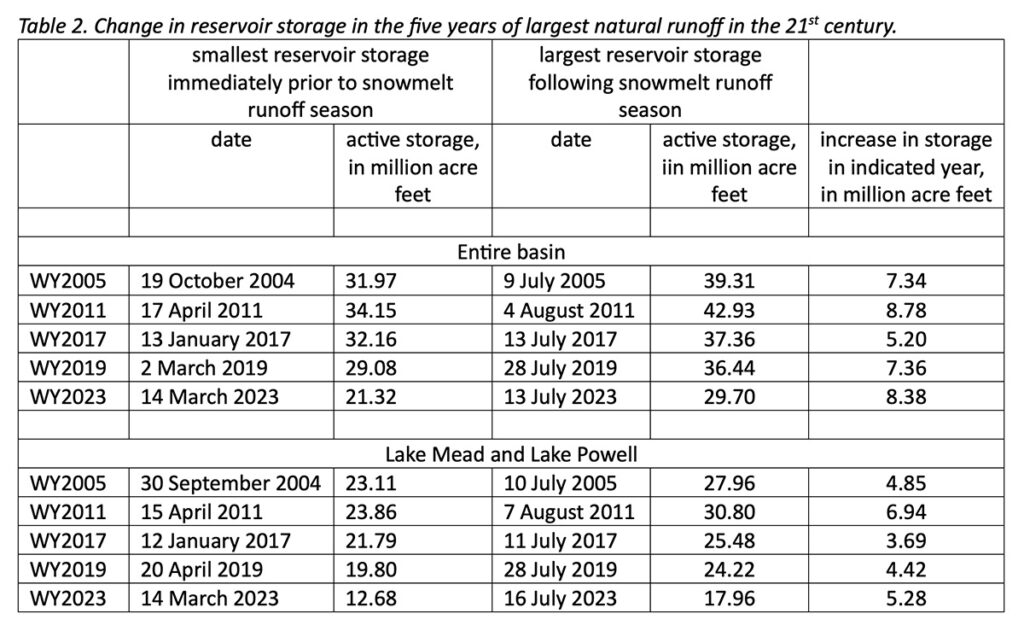

Reservoirs are the ultimate buffer between water use and a water crisis, especially during extreme dry spells, such as occurred in 2002-04 and 2020-22. Although the runoff in 2002-04 was worse than the later event, the later one caused relatively more alarm, as reservoir storage was already low. Then the exceptional water year in 2023 provided the second largest runoff of the 21st century and restored some lost storage in the reservoirs. We still have a long way to go to return the reservoir system to full conditions (see blog post, Water Year 2023 in Context: a cautionary tale). There is an imperative to retain as much of the 2023 runoff as possible to create a buffer, especially if another dry spell occurs.

Some Context

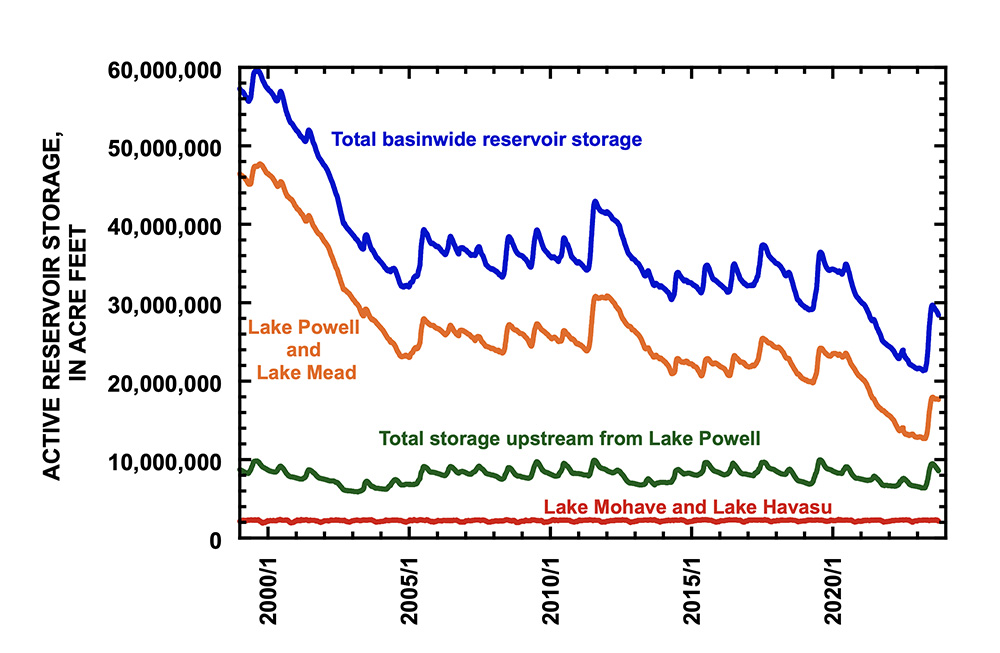

The last time the basin’s reservoirs were completely full (in fact, a bit overfull) on July 15, 1983, they held 63.6 million acre feet (af) of water, as reported in Reclamation’s basin-wide reservoir database. Today, the maximum capacity of the reservoir system is a bit extended, due to completion of few new reservoirs (e.g., McPhee and Nighthorse). Reclamation’s database, although quite complete, and reporting the status of 42 reservoirs, does not include every reservoir in the basin (for example, Wolford Mountain, Stagecoach, and Elkhead reservoirs). The data as it stands is still useful for assessing the present condition of basin reservoir storage.

During the 21st century, 60-80% of all reservoir storage (not including storage on Lower Basin tributaries) has been in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two largest reservoirs in the United States. Further downstream on the mainstem river, 4-8% of the basin’s storage occurs in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu. These reservoirs are typically maintained near full pool. Lake Havasu is operated to provide a stable pumping forebay for California’s Colorado River Aqueduct and for the Central Arizona Project, and Lake Mohave is operated to maximize hydroelectric power generation and to reregulate releases from Lake Mead. These four reservoirs – from Lake Powell to Lake Havasu — store water to meet the needs of the Lower Basin and Mexico. Because there are no significant withdrawals from Lake Powell or in the Grand Canyon, Lake Powell and Lake Mead can be considered one integrated reservoir unit, even though the reservoirs are in the Upper Basin and Lower Basin, respectively. The reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell provide storage for Upper Basin agriculture and trans-basin diversions and account for 16-32% of the total storage in the watershed.

The amount of water in a reservoir is a result of the difference between the amount of water that flows in, and the amount released downstream, as well as the amount that evaporates or seeps into the regional ground water. For ease of writing, “loss” here means the amount of reservoir storage decline—loss results from changes in reservoir inflows, reservoir releases, and evaporation.

How are we doing this year?

Conditions this year are “so far, so good.” Between July 13, 2023, when total storage reached its maximum — 29.7 million af — and November 30, 2023, storage declined by 1.73 million af (Fig. 1). The total gain in storage that occurred from the 2023 snowmelt runoff was 8.38 million af. We have now lost 21% of that original gain. Losses between mid-July and November 30 were only 68,000 af greater than the total losses between mid-July and October 31 (see blog post, Protecting Reservoir Storage Gains from Water Year 2023: how are we doing?), and 79% of the total reservoir storage gained in the 2023 runoff season remains.

Since mid-July, the loss in storage has occurred in three places:

Total storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell between mid-July and November 30 has declined by 540,000 af;

Total storage in other Upper Basin reservoirs of the Colorado River Storage Project (Blue Mesa, Morrow Point, Crystal, Fontenelle, Flaming Gorge, Navajo) during the same period declined by 500,000 af; and,

Total storage in other Upper Basin reservoirs, such as Granby, Dillon, McPhee, Strawberry, Starvation, and Nighthorse, declined by 620,000 af.

Figure 1. Graph showing reservoir storage in 2023 in three parts of the watershed, as well as the total storage. Note that most of the loss in basin-wide storage was due to decreases in storage upstream from Lake Powell.

The rate of loss this year is much lower than in any other of the previous ten years (except for 2014 when there were large monsoon season inflows), suggesting that current policies of reducing consumptive use may be working. I calculated the loss in each of the last ten years, beginning on the day of maximum basin storage (Fig. 2). Each curve in this graph represents the loss in storage from the peak of each year. For example, on November 20, 2020, reservoir storage was 4.42 million af less than the peak storage that had occurred on June 18, 2020. In contrast, storage on November 30, 2023, was only 1.73 maf less than the peak storage that occurred on July 17, 2023.

Figure 2. Graph showing loss in basin-wide storage from the maximum storage of each year. Note that the losses in 2023 have been less than in any other year except 2014.

Management policy concerning where storage is retained and where storage is reduced appears to be in transition. In contrast to previous years, storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead is being reduced very slowly (Fig. 3). Today, storage in these two reservoirs is only 544,000 af less than the mid-July peak, whereas storage in these reservoirs in 2020 was 2.85 million af less than the maximum storage of that year.

Figure 3. Graph showing loss in the combined contents of Lake Powell and Lake Mead from the maximum storage in each year. Note that the losses in 2023 have been less than in any other year, indicating that the combined water storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead remains relatively high.

Next week, Colorado River water users and managers will gather for the 2023 Colorado River Water Users Association meeting in Las Vegas. The river’s stakeholders are in the midst of negotiating new agreements on how to share the pain of water shortage during the ongoing Millennium Drought, and there is significant interest centered on this event.

Although we ought to feel good about our collective effort to retain desperately needed storage, we must remain vigilant to continue the hard work to reduce consumptive use. Today’s total watershed reservoir storage of 28.0 million af is the same as it was in early May 2021 in the middle of the 2020-2022 dry period (Fig. 4). Let’s hope for a good 2023/2024 winter and spring snowmelt.

Figure 4. Graph showing reservoir storage in the 21st century in three parts of the watershed, as well as the total storage. Note that conditions on 30 November 2023, at the far right hand side of the graph, are similar to conditions in early May 2021 and less than during most of the 21st century.

Acknowledgment: Helpful suggestions to a previous draft were provided by Eric Kuhn.