We’re not running out of water in the West. What we’re running out of is cheap water in the West.

Pollution cleanup as a solution to water supply shortfalls

As Southern California looks at its next water supply steps, one of the top items on its agenda is cleaning up groundwater contamination. It’s cheaper than building more storage. So says MWD’s Jeff Kightlinger:

I think you’re going to see the next wave of investments over the next decades in Southern California focused around issues like recycled water and groundwater basin cleanup. We see that as better bang for the buck.

Our increasingly efficient use of water

Another reason for optimism about our ability to solve our water messes:

[I]n most regions, the water needed to feed one person decreased even if diets became richer, because of the increase in water use efficiency in food production during the past half-century.

Global Changes and Drivers of the Water Footprint of Food Consumption: A Historical Analysis; Chen Yang and Xuefeng Cui; Water 2014, 6(5), 1435-1452

Thanks to Linus Blomqvist for the pointer.

The Four Corners is a complicated place

George Maxwell, Colorado River irrigation and the “Asiatic menace”

When I first ran across the rantings of George Maxwell as the Colorado River Compact was being developed in the 1920s, their racism seemed almost comical. Here he is in a written submission to the 14th Meeting of the Colorado River Commission, Nov. 13, 1922 (pdf from University of Colorado):

The flood menace must not be used as a ‘stalking ox’ behind which to conceal a plan to create an Asiatic Menace in Mexico more dangerous by far to the United States of America than the original flood menace.

As between the submergence of the Imperial Valley by floods and the devastation of Southern California and Arizona in an Asiatic War, the loss of the Imperial Valley would be the lesser of the two evils.

Maxwell’s fear was that any water allowed to pass into Mexico would be used in the development of an “Asiatic” irrigation colony that would be used as a beachhead for an invasion of the United States. Here’s historian Eric Boime:

This is not just some crazy old racist. George Maxwell was a pioneer of the reclamation movement, one of the authors of the key legislation that brought federal policy and money to bear on the Colorado River. I’m intrigued by Maxwell because in the years after the 1922 approval of the Colorado River Compact, he was enormously influential in Arizona, persuading state officials not to ratify the compact – a stand that continues to echo in contemporary water management.By 1923 his long, meandering letters to former acquaintances at the U.S. Geological Survey, sometimes spaced only twenty-four hours apart, fretted about “Asiatic cities” at the head of the Gulf of California, capable of launching “a fleet of aeroplanes [sic] with poison gas enough to wipe out the population of southern California some morning before breakfast.”

Boime, in his fascinating essay “Beating Plowshares into Swords”: The Colorado River Delta, the Yellow Peril, and the Movement for Federal Reclamation, 1901–1928 (Pacific Historical Review Vol. 78, No. 1, February 2009, paywalled) points out that Maxwell died penniless and ignored. But what I did not realize until I read Boime was the remarkable racial underpinnings of the early reclamation movement. The story of reclamation’s aspirations to social engineering has been often told – the way an empire of 160-acre farms would lure Americans from urban decay into an idyllic pastoral future, one family at a time. What I’d not previously understood was the rich, full racism of the vision.

Here, for example (as quoted in Boime) is the Imperial Board of Supervisors in a 1919 Congressional hearing:

“If we build an all-American canal, we will have [thousands of] free, prosperous Americans building homes and schoolhouses on land watered by water that has never touched a foreign soil and water that . . . Japs and Chinese have not used to bathe in.”

And here is Boime’s description of the views of no less a reclamation luminary than Elwood Mead, who headed the Bureau of Reclamation during the historic construction of the dam at Boulder Canyon (they named a big reservoir after him):

Mead perceived industrious, upwardly mobile Japanese to be the greatest menace to American rural life. If, in fact, Anglo-Saxon family farmers were the key to revitalizing the nation’s institutions, non-Anglo-Saxon family farmers would be the source of their ruin. Japanese agricultural success, Mead asserted, stemmed from “ancient, alien instincts” that would surpass the “American individualist [like] child’s play. . . . Anglo-Saxons and Mongolians cannot live side by side,” he argued, “and neither will give way to the other without a conflict.”

So yeah, George Maxwell may have been batshit crazy at the end (“aeroplanes with poison gas”) but his views on irrigation and race were not terribly far from the mainstream of his day.

Biographical background on George Maxwell from the Arizona State Library.

Little Water

The aptly named “Little Water,” on the Navajo Nation in northwest New Mexico.

The weather station at Canyon de Chelly, which looks like it’s about 30 miles away across the border in Arizona, has recorded 1.52 inches (3.86 cm) of rain so far in 2014, which is less than half of mean precip through May 24. It’s a desert.

a stupendous achievement by means of irrigation

In no part of the wide world is there a place where Nature had provided so perfectly for a stupendous achievement by means of irrigation as in that place where the Colorado River flows uselessly past the international desert.

– William Smythe, Sunset Mangazine, 1900, quoted in Eric Boime, “Beating Plowshares into Swords”: The Colorado River Delta, the Yellow Peril, and the Movement for Federal Reclamation, 1901–1928, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 78, No. 1 (February 2009)

Someone built this a long time ago

Back from Mesa Verde and filing my pictures, there is this:

More impressive to me, in some ways, than the big stuff. Eight centuries ago, some people went to a lot of trouble to climb up to that upper alcove and build a little wall. Maybe they built more. I don’t know.

Water is different than other industrial raw materials, but how, and why?

NPR’s Dan Charles had a nice piece on California’s drought this week digging down a layer into how farmers are actually responding to California’s drought.

They are:

- Fallowing fields of annual crops like corn to ensure they have enough water for their permanent crops, like almonds.

Sarah Woolf takes me on a tour of her family’s farm, and points toward one dry field. “It had onions in it last year, and we’re not farming it at all, because we don’t have enough water supply,” she says.

- Pumping groundwater to make up for surface water shortfalls.

According to a new report from the University of California, Davis, the extra water that farmers will pump from their wells this year will make up for about 75 percent of the cutbacks in water from dams and reservoirs.

Of course this cannot go on forever. Groundwater levels are dropping:

Woolf tells me that just this morning, she heard about problems at one of their wells. “We have to actually drill down and drop the well deeper, which is a very bad sign,” she says. It means that the water table is dropping; the aquifer is drying up.

I’m intrigued by the question of how this is different than other extractive human activities that depend on fluctuating availabilities of raw materials needed to do the things we do in a modern world.

Earlier this month, Lissa and I spent days wandering aimlessly around the San Juan Basin, the desert country where the Four Corners states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona meet. It’s an area that lives with the ups and downs of oil and gas production, and it’s been down lately, bypassed by the horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing boom.

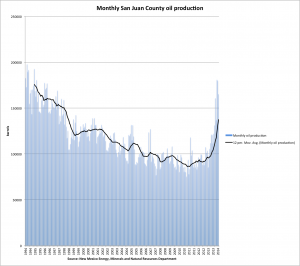

As my Albuquerque Journal colleague Kevin Robinson-Avila has written, there’s a rock layer called the Mancos shale that has shown promise using the new techniques, and as Lissa and I were wandering the back roads, we saw a lot of activity – drill rigs, fancy new oilfield services pickups. And there’s some indication in state data that there’s been an uptick in oil production in New Mexico’s San Juan County in the last six-plus months.

Here’s my question: Why is the societal conversation about the ebbs and flows of one natural resource (water/drought) so different from the other at issue here (oil production)? In both cases you have communities dependent on the resource that rise and fall in response to its availability, and adjust to its presence or lack.

In California’s central valley, farmers adjust to changing water available by adopting new techniques and changed cropping practices. In some cases, as the resource disappears completely (I’m thinking here of depletion of groundwater that can be economically extracted for farming), this particular human activity will simply go away. In other cases, farmers will adapt, shifting cropping patterns, as we’ve seen on the high plains. This looks a lot like an oil and gas economy of the type Lissa and I saw in northwest New Mexico.

I’ve catalogued some similarities here. What are the differences? Why are the societal conversations about the two resource issues so different?

update, Brian Jordan had some comments on twitter:

@jfleck 2/2 I don't think there's as much diff. as suggested…there's a "Peak X" meme for every natl' resource but our selection bias is H2O

— Brian Jordan (@jordanbrianl) May 25, 2014

You can’t use negative water – the dilemma of water policy planning by projection

Kyle Mittan had some nice straight talk recently in the Tucson Weekly from the University of Arizona’s Sharon Megdal about Arizona’s projections that it’ll need another million acre feet per year of water by 2060:

“A million acre-feet is a lot of water,” she said. “But is that the right number, or is that symbolic of the fact that if communities in the state wish to grow and develop in the ways they’re anticipating now, there’s going to be a need to figure out how to meet the water needs?”

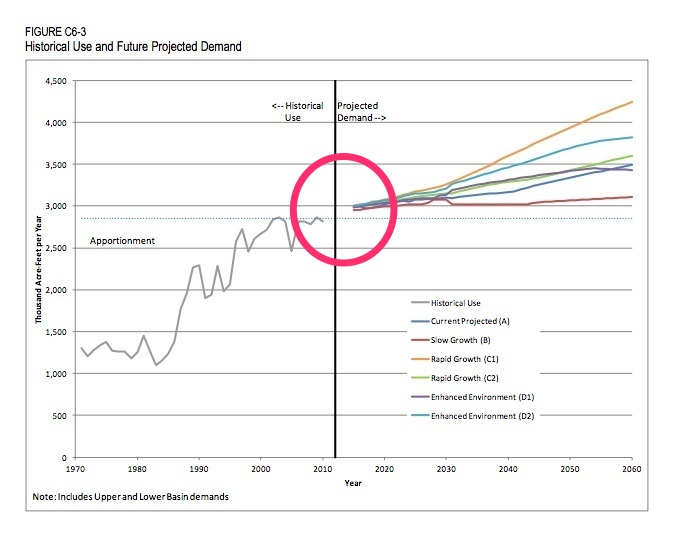

Embedded in the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study is a lot of questionable data of the following form:

You can see that for a decade, Arizona’s water use flat-lined. And yet the projections call for a big jump and continued rise in water use, well above the state’s available Colorado River apportionment. That obviously can’t happen, and in response one of a number of things will happen. Arizona’s water use will stop rising (which seems to be supported by the history of the past decade) or Arizona will find more water.

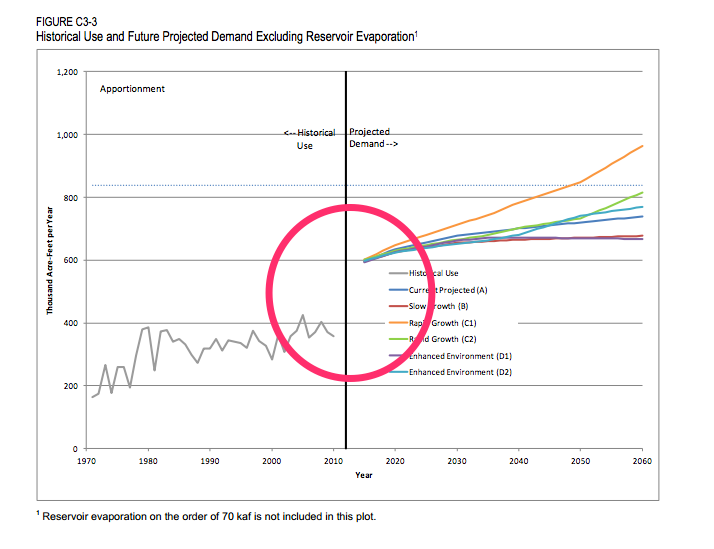

I don’t mean to single out Arizona here. Its water use projections in the Basin study are among the least daft. Consider my own state of New Mexico:

A projected 50 percent increase in water demand over a five year period, after a decade that’s been mostly flatlined? That’s crazy!

When I was a youngster, during the dawning of my Earth Day consciousness in the early 1970s, I was a maniac about recycling because I heard we were going to run out of landfill space within, like, a decade or something. Of course we didn’t, because we built new landfills. That realization – hey, people adapt by building new landfills! – drives a lot of my thinking about water today. We obviously can’t use negative water, so the graphs you frequently see showing water demand outstripping supply – a million acre feet! – are crazy talk. Faced with hard choices, Arizonans (and New Mexicans and everyone else) will either figure out how to get more water, which seems expensive and hard, or figure out how to use less, which so far has been a very successful path, as the graphs above demonstrate. At least the left-hand sides of the graphs showing actual historical use. The right-hand sides of the graphs seem to me like a bizarre unreality.

I don’t mean to criticize the Basin Study here, because I think it’s done an enormously valuable service. The study’s authors simply asked the states what they thought they would need, and worked through the results. It’s an incredibly useful exercise if we take the right message away from planning exercises like these – what people say they think they will need is a good starting point for thought exercise Megdal suggests.