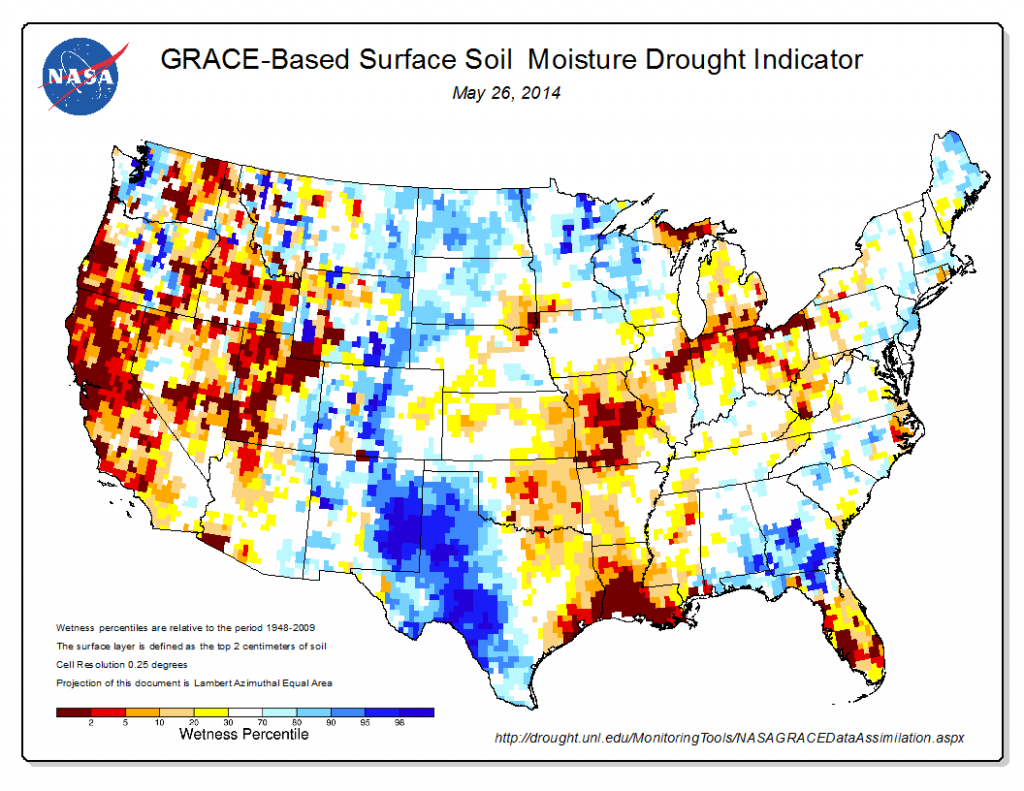

Six turkey vultures roosting at Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde, May 2014, by John Fleck

Five years ago, Lissa and I stopped to talk to a ranger on the Petroglyph Point Trail at Mesa Verde. We’d been admiring the turkey vultures soaring above the canyon, and the ranger clued us in. If you like turkey vultures, she told us, go to the Spruce Tree House overlook at dusk tonight and you’ll see a whole bunch of ’em coming in to roost.

We did, and Oh My. That year, I think it was in July, we counted more than a hundred at one time. They soared in a few at a time – one, two, three, four – over a period of hours. They’d sit on the cliff opposite, warming their wings in the setting sun, before settling in for the night, one at at time, in the trees in the canyon below Spruce Tree House. It was a life experience. That summer, we detoured on our return from vacation to see it again.

So this year, on vacation in the same territory earlier this month, we went back. After a dinner of Navajo tacos at the cafeteria, we perched on the porch on the back of the ranger station, overlooking Spruce Tree House, and waited.

Vulture-watching perch, Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde, May 2014

Turkey vultures or not, it’s a lovely spot. We brought all the glass we had at our disposal – two cameras, two pair of binoculars. And snacks and drinks.

This year, the rangers had a second clue for us. While it was still early in the season (only a few dozen turkey vultures had arrived, they said), the Mesa Verde birds had added a routine to their show. At dusk, the rangers explained, turkeys who lived in the woods atop the cliff would walk out, one at a time, perch on the cliff, and then fly clumsily in a downward path (these are turkeys, remember) toward the trees the vultures had staked out for them.

Turkey, staring into the abyss, by L. Heineman, May 2014

We had at least two hours of vultures coming and going in small numbers, with a few roosting in the trees, before the first turkey showed. It was hilarious. It walked out of the woods opposite along the hiking rail, where the humans go. It wandered off to the north, then a second showed, and eventually one of the turkeys walked out to the edge of the cliff.

Turkeys are not known for the ability to fly, and it showed. It was more a leap, a clumsy flapping, and then a no-turning-back landing. If there was already a vulture on the chosen tree branch, tough shit. The vultures were hip to this routine, and seemed to understand that the turkeys didn’t have a lot of maneuverability. The vultures moved.

It was dusk, and neither of us had the lenses to really capture the comically remarkable turkey vulture flight in the low light, but it was a treat. Eventually, six turkeys had joined the vultures in the trees by the time it got too dark to see any more. This one will have to do, and you’ll just have to take my word for the fact that this is a turkey, flying downhill from the top of a cliff toward a tree, and that watching them pull off this stunt added, if that is possible, to the life experience of vultures at Spruce Tree House:

Turkey, taking flight to its Spruce Tree House roost, May 2014