Water managers in the Upper Colorado River Basin are beginning to roll out details of their contingency planning aimed at preventing Lake Powell from dropping to troublingly low levels.

Among the key steps being discussed, according to a presentation Monday by New Mexico’s Kevin Flanagan to his state’s Interstate Stream Commission (more over on my work blog):

- cloud seeding

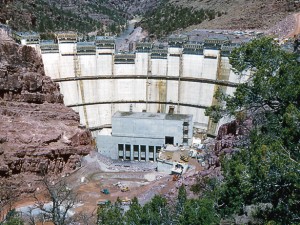

- reservoir reoperation to move water from upstream reservoirs, especially Flaming Gorge in Wyoming, to Powell to keep Powell’s levels up

- “demand management” – willing buyer/seller agreements to fallow farm land, for example

The idea, Flanagan said, is to take proactive steps ahead of trouble, to avoid the more dire problems that might happen if Lake Powell drops too low to generate power or make its legally required deliveries past Lee Ferry to the Lower Basin.

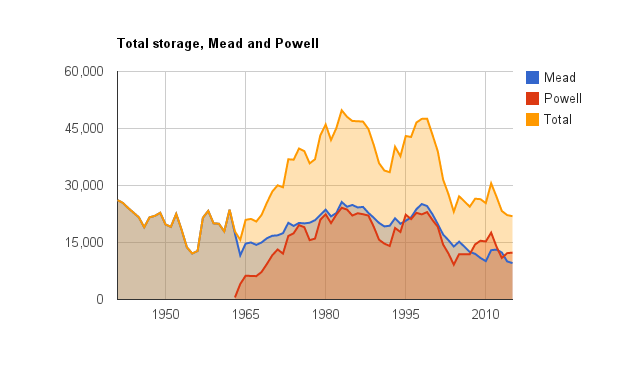

It is a testament to the difficulty of the underlying problems that we don’t quite agree about what those delivery obligations are. The Colorado River Compact clearly says we’ve got to deliver 7.5 million acre feet per year, or 75 million acre feet averaged over any rolling ten consecutive years. A Lower Basin lawyer would argue that we Upper Basinites also owe the river an additional 750k acre feet per year, our share of the water that must be delivered to Mexico. For reasons arcane, all that bundles to an annual obligation to deliver 8.23 million acre feet per year, or 82.3 million acre feet over ten years. Either way, whether the obligation is 75 million or 82.3 million, we’re in good shape for now. The most recent rolling total is 90.8maf, so we’ve got plenty of slack in the system short term.

Longer term, though, there’s a one in twenty chance that Powell would hit minimum power pool elevation of 3,490 between now and 2019, according to Bureau of Reclamation modeling, and a one in five chance between now and 2026.

Backers of the contingency effort are strongly pushing the argument that the power pool stuff matters because power generates something like $200 million per year money (updated per comment, I’m now unclear on the amount) that’s funneled into Upper Basin environmental compliance programs. Upper Basin folks need that money for their Endangered Species Act compliance coverage, I’m told. (I’ve not looked closely at this yet, I’m taking them at their word. The flow of water is hard enough, I’ve no deep understanding of the flow of electricity and the money related thereto.)

If Powell gets really low – 3,440 and below – it becomes impossible to meet delivery obligations at all, because you simply can’t get the water out of the lake to send downstream. By 3,420, the maximum you could release, for example, is 6.4 million acre feet, according to Flanagan’s presentation. I did not know this.

The reoperation of Upper Basin dams – Blue Mesa, Flaming Gorge and Navajo) is the most interesting part of this to me. The scenarios presented by Flanagan show Flaming Gorge doing the bulk of the work. Anywhere from 1.9 maf to 3.4 maf over a 20-year period would be moved to Powell instead of stored at Flaming Gorge. Navajo and Blue Mesa make far smaller contributions. Navajo, for example, contributes 5kaf to 10 kaf per year under the scenarios presented. I don’t really understand the Upper Basin reservoir operating rules, so I’ve no idea how decisions are made now to keep water in Flaming Gorge versus sending it on down, and how that rule set might need to be changed. Readers who know, please fill in gaps in the comments, and once I understand this better, I’ll try to return and write stuff here that explains it all.

Flanagan’s final presentation slide noted something worthy of note – completing these plans will require “navigating difficult political sensitivities”. Yup. That sounds about right.