In my world, the 1976 tree ring analysis of the Colorado River’s long term flow done by Charles Stockton and Gordon Jacoby stands as one of the great works of policy-relevant science. But by the time I came on the scene, “Stockton and Jacoby”* (pdf) was just a marker, a signpost along our path to understanding the mistakes we made in allocating the Colorado River’s flow. I’d never looked at the details of how the work came about until we got news today of Jacoby’s death, and some reminiscing by some of Jacoby’s colleagues sent me down the rabbit hole of history to the wonderful story Jacoby told to oral historian Ronald Doel in 1996.

Stockton and Jacoby, 1976

The National Science Foundation was funding a broad research effort into the impacts of the completion of Glen Canyon Dam and the filling of Lake Powell. Jacoby thought tree rings might be an interesting tool for understanding the long term history of flows on the river:

[I]n doing some of the water aspects, I heard somewhere — I can’t really cite a specific reference — this idea of using tree rings to find out about water supply. They realized first you have to know how much water is going to come into this reservoir. And I heard somewhere this concept of using growth rings of trees to estimate stream flow. And so I went and talked to Chuck [Charles] Stockton at the tree ring lab in Arizona and he’d been working on the Colorado River flow. So in the next contract that I put in, I put in a subcontract for us to work together on this.

Their findings were disconcerting.

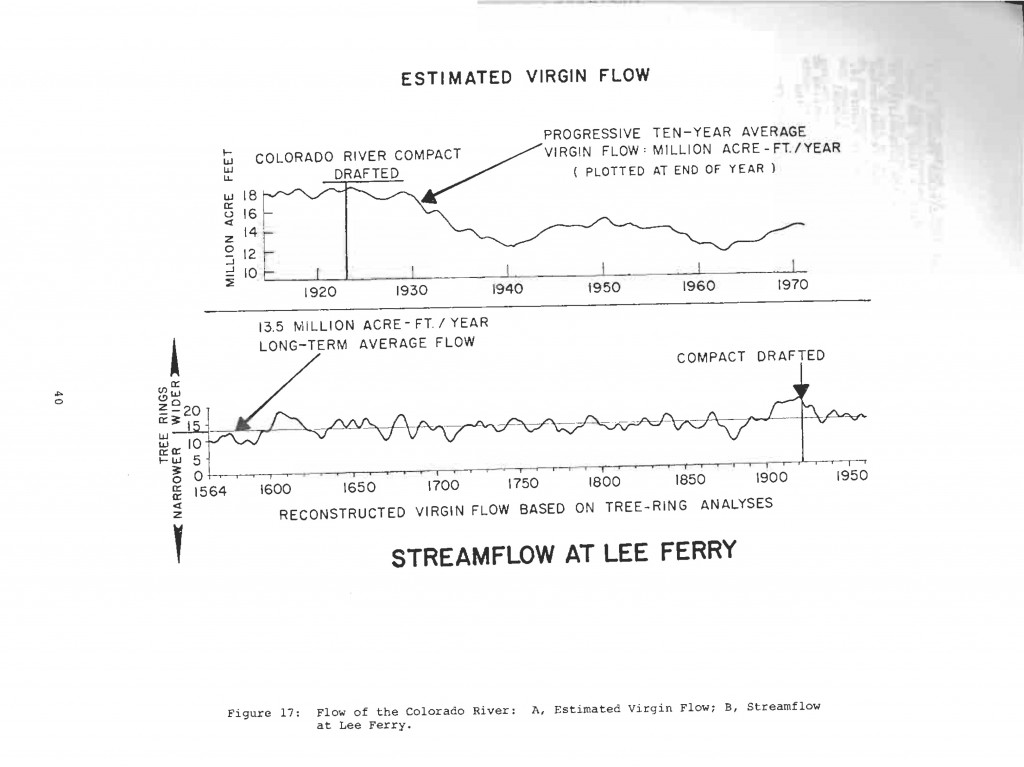

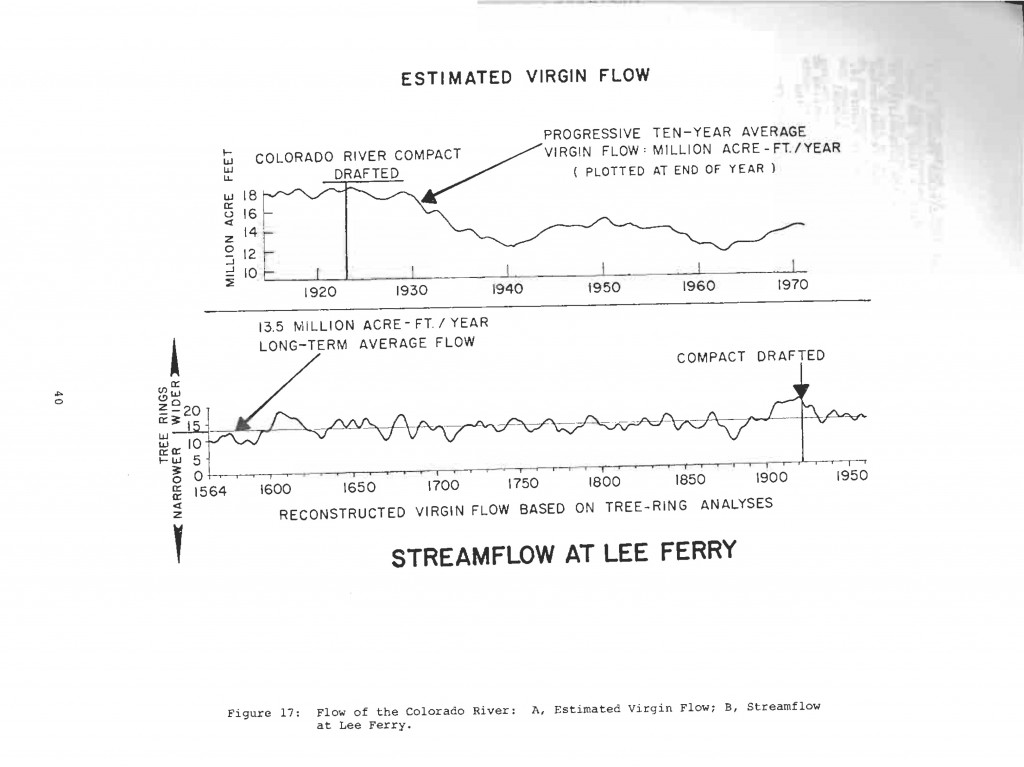

The Colorado River’s allocation of 7.5 million feet annually for the Upper Basin, 7.5 million for the Lower Basin, with another 1.5 million acre feet tacked on for Mexico, had been negotiated during an unusually wet time. A very unusually wet time. Here’s their graph:

Lee’s Ferry flow, Stockton and Jacoby, 1976

Jacoby describes the response when he first presented the results, at a meeting of the AAAS in 1975:

At the end of my talk I think there were one or two agency people in the audience actually jumping to their feet and yelling; an interesting scene. I think I was predicting hydrologic bankruptcy with relation to these ideas and real stream flow. And so that got a lot of people excited.

There’s a history of great science in the years since clarifying the paleoclimate record and refining our understanding of the Colorado River’s flow, especially Woodhouse et. al in 2006. But Jacoby’s basic message still stands.

* If anyone has a link to a web-based copy of the original report, please share in the comments? Thanks.

update: Thanks to Kevin Anchukaitis, here’s a link to the original (big pdf).