Peter Culp, Robert Glennon and Gary Libecap have published an excellent new analysis of the potential for water markets to help us dig out of the western United States’ water mess:

Culp, Glennon and Libecap

Water trading can facilitate the reallocation of water to meet the demands of changing economies and growing populations. It can play a vital role in encouraging conservation and stewardship of water supplies in a way that can address cultural, social, and environmental priorities. It can facilitate building a structure for managing the ever-increasing risks of greater variability in water, including through methods such as insurance contracts, hedging tools, water banking, and other mechanisms. Deploying market tools in the allocation of water can help us to overcome the growing fragility and vulnerability of the water management institutions and infrastructure in the American West.

I agree, and their new work offers a great menu of policy options to move down this path. In brief (again quoting Culp et. al):

- Reform legal rules that discourage water trading to enable short-term water transfers.

- Create basic market institutions to facilitate trading of water.

- Use market-driven risk mitigation strategies to enhance system reliability.

- [B]etter regulate the use of groundwater by monitoring and limiting use to ensure sustainability, and by bringing groundwater under the umbrella of water trading opportunities.

- To make water markets work at scale, strong federal leadership will be necessary to promote interstate and interagency cooperation in water management

This is great stuff. But how do we actually do any of them?

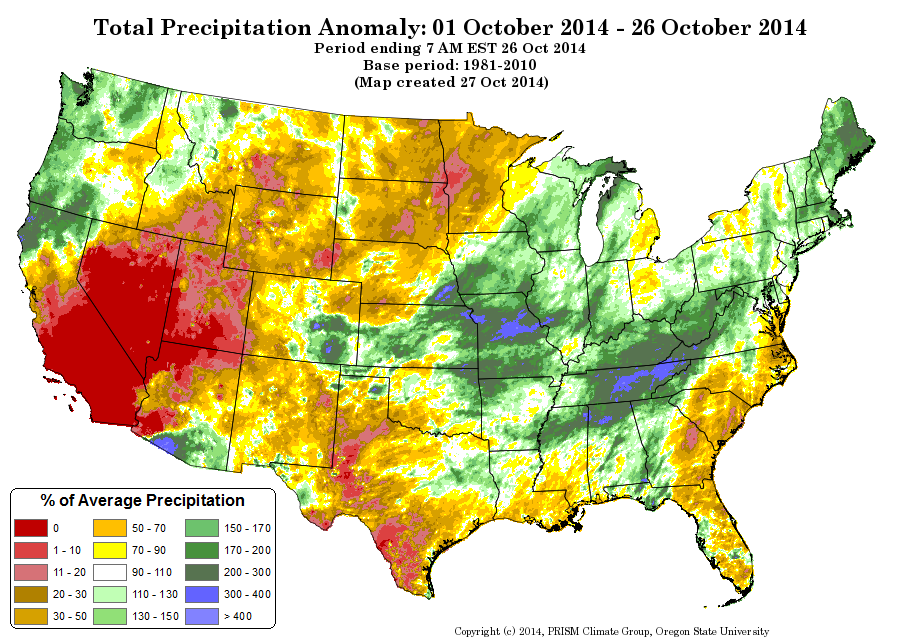

Each of their first four bullet points is a staggeringly difficult task that will require enormous institutional capacity within the states to carry out. Consider California’s efforts to move on number four, for example. In the midst of the drought of record, with overwhelming problems caused by groundwater pumping, all California could manage was some feeble legislation aimed at just the first part – monitoring and limiting use to ensure sustainability at some future point in time sorta maybe. This is not for lack of smart scientists and policy people pointing out that the problem is deeper and requires stronger action. This rather reflects a shortcoming of the political system that has left us at with a sub-optimal equilibrium because of the ability of individual players, acting in their own short term interest, to block progress toward a more socially optimal solution. We’re stuck in the wrong spot, and years of water politics in California, despite calls to move off of it, have failed. From Kosnick:

There exists a socially optimal level of production of a good…, but without coordination of the overlapping players involved, optimality is not guaranteed. For example, this is a prisoner’s dilemma, where each player acting independently in his own best interest fails to internalize the externalities of his actions on the other players, and so a suboptimal (if dominant strategy) Nash equilibrium results…. Self-interest and a limited perspective reduce the benefits to society as a whole.

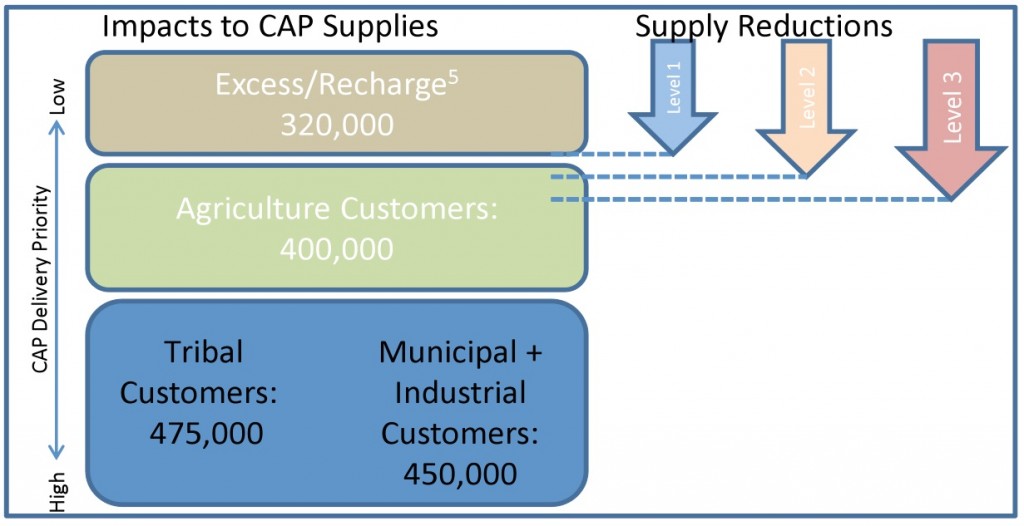

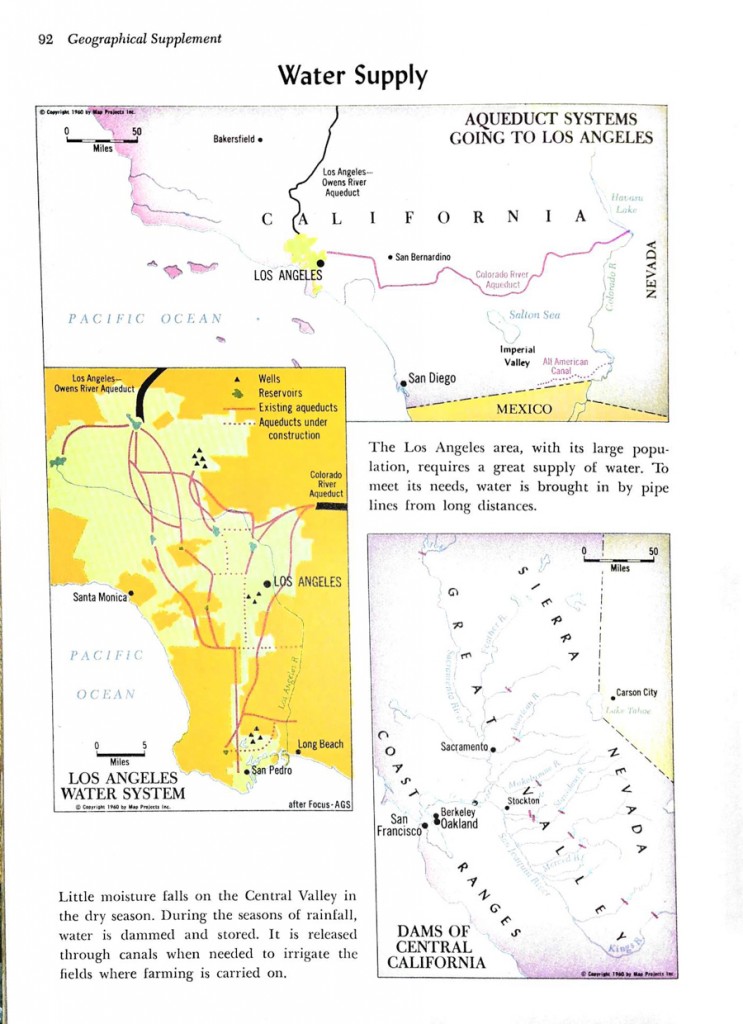

Not to pick on California, but nearly two decades of experience in trying to put together markets to move Colorado River agricultural water from Imperial and Palo Verde to the urbanized coastal plain (Glennon’s Unquenchable discusses the efforts at length) shows how hard this can be.

discusses the efforts at length) shows how hard this can be.

Culp et. al clearly get the difficulty of the task that they’re proposing. In a discussion of the impediments posted by existing water law doctrines, for example, they write:

Comprehensive reform of these doctrines would be controversial and could take decades to implement.

But I think they’re on to something when they suggest the following approach:

[S]tates could immediately act to facilitate effective short-term water trading. Particularly important would be for states to encourage existing water users to invest in conservation by allowing users who free up water to lease their water savings on a short-term basis to other users. This strategy offers obvious, real-world opportunities for win-win solutions, benefitting all parties and increasing economic efficiency.

Having spent years watching the New Mexico legislature’s lack of institutional capacity to make even simple water rule changes, and watching California thrash about this year in the midst of genuine crisis, I think Culp and his colleagues are a tad optimistic to suggest this could be done “immediately”, but whatever. I’m all for optimism. And I’d file this under the critical category of “baby steps,” smaller and relatively easier things that can be done that provide shorter term benefits and the learning experience to help amass the necessary social capital to take on the harder challenges to come.

I also think they’re on to something important in suggesting a federal role:

The federal government has a key role to play in assisting the development of water markets through its leadership on water issues, facilitating large-scale planning and interstate cooperation, developing critical data and information, modernizing the management of existing federal projects, and reforming existing federal agricultural policies.

Minute 319, the U.S.-Mexico agreement that, among other things, allowed last spring’s Colorado River Delta environmental pulse flow (and which Culp helped design) is a great “baby steps” example. It includes some of the elements Culp, Glennon and Libecap are asking for (albeit dressed up quite differently), but it was as much about learning how to do stuff as it was about actually doing stuff. It also demonstrates the importance of the role of the U.S. federal government.

The important thing we need recognize here, I think, is that the investment in the social capital needed to do these things, an investment in what I’ve sometimes called the “institutional plumbing”, is every bit as real and important as the investment in pumps and canals and dams that make up the physical plumbing of water in the West.