Santa Fe, Christmas 2014

Coming, not quite so soon: Beyond the Water Wars

So the folks at Island Press will be publishing my book, tentatively titled Beyond the Water Wars, about the problems facing the Colorado River Basin and how we might fix them. I couldn’t be happier.

Its basic themes will be familiar to readers of this blog – the end of the age of fat reservoirs and full canals, of vast suburban lawns and alfalfa fields stretching as far as the eye can see; the growing but uncertain shift away from legal confrontation, toward collaborative arrangements to share; the risks of the system crashing if we fail to pull off that shift.

We don’t have a firm schedule yet, but it looks like publication is a couple of years away. (Very different from the publication pace of my newspaper life.)

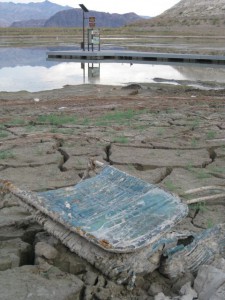

I’m excited to work with Island Press. The people I’ve been dealing with in developing the project have been extraordinarily smart about helping me think through how I might turn my sometimes mushy ideas into a readable and therefore useful book. Now it’s on me to write that book. A lot of it will be based on work I’ve done over a number of years, and I plan to spend the next year doing a lot of fresh research and reporting. (Alfalfa fields, stranded boat ramps, suburban fountains. Road trips!)

I can still vividly remember standing on the south rim of the Grand Canyon as a little boy (I think I was five), looking down in awe at the river below. If you’ve been there, you understand that you get only glimpses, tiny bits of the brown ribbon peeking into view, a river obviously there (witness the gaping hole it created) but elusively out of a little kid’s view.

Years later when I boated the Grand Canyon, I realized that it’s the same way looking up from the river. Often you can’t see the rim, can’t see out of the marvelous canyon you’re in. (Metaphor alert.)

I’ve been on and around and thinking about the river ever since, and have wanted to write about it since I was grown enough to want to write about things. But I don’t think I understood what the story was until the spring of 2010, when Jennifer McCloskey, then of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Yuma office, sent me off driving down the levee road behind the Bureau’s Yuma headquarters. A couple of miles downstream from her office, what’s left of the river hits Morelos Dam and the Colorado River ends. By that time I was already deep into the politics and policy side of the thing, trying to make sense of what we had done and might do with the Colorado. But nothing quite prepared me for seeing this river I’d been so obsessed with my whole life simply stop.

First Colorado delta pulse flow science findings

The International Boundary and Water Commission today released its initial science report (pdf) on this spring’s Colorado River pulse flow. A few key bits:

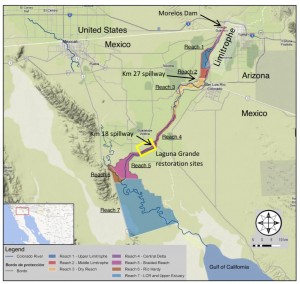

- When you add water, stuff grows. Satellite imagery in June ’14 compared to a year earlier showed a 36 percent increase in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. The NDVI increased in all but one area (the area where vegetation was cleared to prepare for flooding and new plant germination, which makes sense).

- Cottonwoods liked it. Tamarisks loved it. In the 4,522 acres of channel and flood plain inundated by surface water, cottonwoods seedlings seemed to take hold in the “Reach 1” and “Reach 4” sections of the pulse flow area (see map). Non-native tamarisk did well everywhere. What happens next depends on the availability of soil moisture fed by groundwater. More study, more time needed.

- Birds seem to be liking the habitat restoration areas. That also makes sense. I’d like them if I were a bird.

- The water table rose, but the rise was really focused in the river channel area between the levees.

A digression that’s important: When I was giving a talk about the pulse flow this fall, a cranky member of the audience took issue with my enthusiasm for all this, pointing to Aldo Leopold’s “green lagoons”, the two million acres that used to be the delta. This was 4,522 acres. As we discuss and describe this very promising experiment at the interface of water management and environmental restoration, it’s important to keep the scales in mind.

“Why do I care about water policy?”

David Zetland really cares about water policy, and he wants you to think better about it:

I confess that I’m not a fan of the “educate the general public” model of water policy problem solving, which might seem odd given my profession as a journalist. That’s an “educate the general public” job, right? But my years in the business have convinced me that what we really need is a set of policies that are robust to the fact that the general public mostly won’t be educated about most things. There are too many things. Way too many things. And they’re all hard.

But I still think that what David’s doing here is worth trying. Because a corollary of my belief is that the right subset of the “general public” can be sufficient to make some headway on hard problems. And to move in that direction, we need to experiment, a lot, in different ways to get through to people.

So, a water calendar? Hmm, that just might help.

How to solve the Colorado River’s problems, or not

tl;dr Everyone on the Colorado River has a legitimate argument that they’ve already sacrificed, and that they have a legal entitlement to what’s left. If everyone digs in their heels on these points, the system will crash. We need to be willing to share the pain. But (scroll to the bottom) there is hope on that front.

longer – The Unhopeful Part

In reading and interviews for my book, I frequently run across arguments of the form that “we” (usually a state, but also sometimes a smaller water-using entity) have already done “our” share for solving the Colorado River’s problems by (insert specific sacrifice already made here).

They all, of course, are right. Consider:

Arizona

With the 1968 approval of the Colorado River Basin Project Act, Arizona agreed to subordinate the bulk of its Colorado River water rights to California in return for the political supported needed to build the Central Arizona Project, which brings water to Phoenix, Tucson, farms and Native American communities in the central part of the state. As a result, Arizona currently shoulders (at least on paper) much of the risk in the face of shortfalls in the lower basin. Under the current law, all of Arizona’s CAP water would be cut off before California loses a drop. That was a major sacrifice.

California

But wait, didn’t California already lose a bunch of drops? Yup, in 2003 California was cut back from its historical use of in excess of 5 million acre feet per year to 4.4 million. That required major water conservation and supply shifts in metropolitan Southern California, and the fallowing of land in the Imperial Valley to free up enough to keep Southern California’s economic engine humming. So yeah, the next big cuts would hit Arizona if there’s a shortage, but that’s only because California already took a big hit.

Nevada

Nevada took its hit coming out of the starting gate. Its allocation of 300,000 acre feet, which goes to Vegas, is basically a rounding error if you’re rounding total Colorado River flow to the nearest million acre feet. Don’t look at Nevada for sacrifice (and even if you did, as I mentioned, sacrificing Nevada completely is just a rounding error on the Colorado River balance sheet).

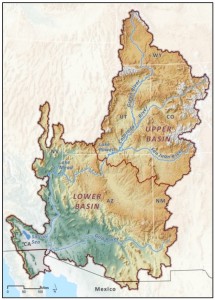

Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico

Under the Colorado River Compact, the four states of the Upper Basin are entitled to use 7.5 million acre feet of water per year. When they signed the deal in 1922, they knew it would be a long time before they would grow into their entitlements, but it was water in the bank to support future growth. In 2012, they only used 4.6 million acre feet, which is pretty typical. The Upper Basin states have clearly done their share.

This isn’t cheap sophistry. Each of the above arguments is a reasonably held, legitimate view. It’s most on display this week in the development of Colorado’s water plan:

Colorado wants to ensure its farms, wildlife and rapidly growing cities have enough water in the decades to come. It’s pledging to provide downstream states every gallon they’re legally entitled to, but not a drop more.

“If anybody thought we were going to roll over and say, ‘OK, California, you’re in a really bad drought, you get to use the water that we were going to use,’ they’re mistaken,” said James Eklund, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

The governance boundary problem

There’s a core issue here that involves the boundaries we draw around our Colorado River water problems. Doug Kenney and his colleagues in the new Colorado River Research Group captured this nicely in one of their first white papers, on “Repairing the Colorado River’s Broken Water Budget” (pdf). Each state, operating within what it thinks are the legal boundaries around its “share” of the Colorado River, has put down on paper a menu of future water options that are wildly unrealistic given the hydrologic reality. There is less wet water in the river than paper water embodied in each user group’s lawyers’ arguments.

Is that realistic? “[I]t’s not, and those water managers that look at the numbers through a basin-wide lens know this,” Kenney and colleagues wrote. But while the Colorado River’s problems have to be solved at a basin scale, much of the water use decision making that matters happens at the state and local level, where the basin wide problems are less visible.

I see this in New Mexico water politics all the time, where there is an expectation that a full firm yield of 96,200 acre feet of water per year through the San Juan-Chama diversion project is our compact-given right. Our sacrifices have been to cleverly live within that allocation, maximizing its beneficial use. The notion that the Colorado Basin as a whole is over-allocated, and that we might have to take a haircut along with everyone else, is simply not part of the discussion.

The hopeful part

To be clear, there are a lot of people up and down the governance ladder, from federal and state to local levels, who aren’t talking this way. Matt Jenkins’ excellent High Country News article today about the Pilot Drought Response Actions program highlights a great example. Here you’ve got a bunch of lower basin water managers trying to find a way to route around this problem, building a couple of different types of institutional widgets to reduce water use locally, but in the context of a basin wide effort.

The PDRA (PDRAP?) attempts to overcome the problem Eklund is referring to (If I conserve, won’t it just end up in California?) by matching conservation commitments. The big metro water agencies in each of the lower basin states agrees to take a haircut and leave the saved water in Lake Mead. Arizona, which is clearly the state with the most to lose, pledges 345,000 acre feet by 2017 (the Central Arizona Project is the actor here); Southern California (Met) pledges 300,000 af; Vegas (Southern Nevada Water Authority) pledges 45,000 af and the Bureau of Reclamation agrees to throw in another 50,000 af. The water stays in Lake Mead, to prop up levels and forestall the risk of shortage.

Matt’s story suggests Arizona’s already nailed down a portion of its savings, in the form of ag agency commitments. This is hopeful stuff.

Tweeting lessons from a California drought

A couple of new papers exploring California’s drought triggered what I thought this morning was some overly simplistic back and forth on the twitters about whether climate change is to blame. I think that’s the wrong question.

The first paper, which I wrote about last week, was the Griffin/Anchukaitis paleo look at the thing. They argued that while as measured by precipitation alone, the last three years were not unprecedented, when you add in the impacts of rising temperatures, it was the worst drought in 1,200 years (which is as far back as their tree ring data go).

Then today, Richard Seager and Marty Hoerling released an analysis suggesting that natural variability was sufficient to explain the drought:

The current drought is not part of a long-term change in California precipitation, which exhibits no appreciable trend since 1895. Key oceanic features that caused precipitation inhibiting atmospheric ridging off the West Coast during 2011-14 were symptomatic of natural internal atmosphere-ocean variability.

Model simulations indicate that human-induced climate change increases California precipitation in mid-winter, with a low-pressure circulation anomaly over the North Pacific, opposite to conditions of the last 3 winters. The same model simulations indicate a decrease in spring precipitation over California. However, precipitation deficits observed during the past three years are an order of magnitude greater than the model simulated changes related to human-induced forcing. Nonetheless, record setting high temperature that accompanied this recent drought was likely made more extreme due to human-induced global warming.

My take:

2/ This drought has taught us important things about the envelope of climate variability California faces, whatever the cause.

— jfleck (@jfleck) December 8, 2014

4/ Scientific back-and-forth helps shine some light, but all science is telling us droughts like this are more likely than we thought.

— jfleck (@jfleck) December 8, 2014

5/ "More likely than we thought" is the key thing to understand, whether natural variability, climate change, or some of both, is behind it.

— jfleck (@jfleck) December 8, 2014

Ostrom on institutional transparency

On twitter the other day, I was joking that I’ve adopted a new approach to my book research: when confronted with a problem, I first ask, “Did Elinor Ostrom write about this?”

Ostrom won the economics Nobel in 2009 for her work on how communities solve common pool resources problems, work that’s central to the themes I’m exploring in my book. But the occasion for my twitterquip was Ostrom’s appearance in an entirely different field, a post by my friend Luis Villa on the issue of free riding in the free software world:

As I’ve explained before here, a major reason why people choose copyleft/share-alike licenses is to prevent free rider problems: they are OK with you using their thing, but they want the license to nudge (or push) you in the direction of sharing back/collaborating with them in the future. To quote Elinor Ostrom, who won a Nobel for her research on how commons are managed in the wild, “[i]n all recorded, long surviving, self-organized resource governance regimes, participants invest resources in monitoring the actions of each other so as to reduce the probability of free riding.” (emphasis added)

This afternoon, I encountered yet another of my realms in which Ostrom applies: institutional transparency. This sunshine stuff is the lifeblood of journalism, and Ostrom is on it! This is from her doctoral thesis, a study of the formation of the West Basin Water Association and other associated institutions for the management of water in Southern California’s West Coastal Basin:

The association has maintained a policy of open files. Any interested person can gain ready access to a wealth of information about the basin by going to the association office. As a consequence, all producers in West Basin have equal access to the same information. No one enterprise can exploit a favored position in the association and control the action of others by eliminating their sources of information. Also, the superior capacity of some of the larger water producers to gain information about the physical system is thus balanced by the association which has command of sufficient resources itself to gain detailed information about the operation of the basin.

And then she adds, in a footnote:

This policy of an open office and open files also enables a researcher to gain access to a wealth of information about how an organization such as this arrives at decisions and implements its decisions – for which the present writer is deeply appreciative.

Always with the hat

When I was a youngster, which was a very long time ago, a guy named Ed Helminski took me into his journalistic embrace. Ed had a business model that involved smart coverage of the U.S. nuclear enterprise, and he made that model work at a time when journalistic models were faltering all around us. His newsletters sold well among private sector types who needed the best intelligence to make business decisions. But they were a must-read for the arms control and anti-nuclear communities as well. (Still sell well. Still are a must read, probably more than ever. Don’t mean to be slipping into past tense here.)

Ed’s publications provided a home for wonky budget and policy arcana that forced me to think better and more deeply about the nature of the nuclear enterprise, the sort of thing far too deep and boring for a newspaper, but that fascinated me. And Ed himself was bigger than life, brash and friendly and deeply supportive and loyal. Once you were in the family, you were in. And always with the hat.

He died Friday, suddenly, and we’re incredibly sad. Services are Tuesday in D.C., and there’s no way I can make it, but know that I’ll be there in spirit.

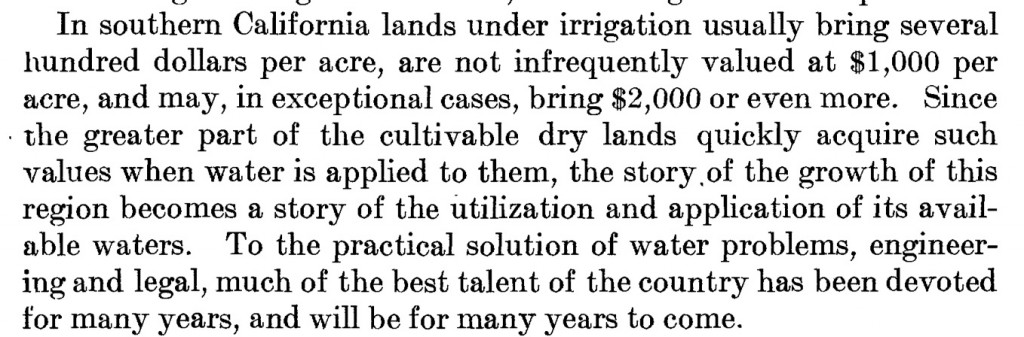

Southern California water: “the best talent of the country”

From the beginning, it was clear that solving Southern California’s water problems would require “the best talent of the country”:

That’s Walter Mendenhall, from a series of U.S. Geological Survey papers published in 1905 inventorying the groundwater resources of the greater Los Angeles Basin’s groundwater resources (before we thought of it as “the greater Los Angeles Basin”). (Water Supply Papers 137, 138 and 139)

For my book, I’ve been tracing what we knew when about the viability of Southern California’s groundwater and the eventually need to import water that ultimately led southern California to build three great artificial rivers. By 1905, it was already clear that groundwater pumping in parts of the region was unsustainable. Here’s Mendenhall:

At these places, therefore, it is evident that there should be no further increase of the drafts upon the underground waters, and that the reclaiming lands from these as a source should cease.

Remarkably, given the urban landscape of the region today, this was farm country. In the Santa Monica area, Mendenhall inventoried 4,000 acres under irrigation. In the Redondo Beach area, there were another 3,280 acres being irrigated with sewage and 8,250 acres from wells. Already, overuse of groundwater and upstream diversions of the Los Angeles River (which fed the aquifer) were reducing the flow from artesian wells, forcing farmers to pump. But Mendenhall concluded that in the Santa Monica-Redondo area:

With continued reasonable use of the underground waters of this area, then, it may be concluded that although the remnant of the coastal plain artesian basin included in it will probably disappear, because the basin is especially sensitive to distant diversions and developments, the ground waters generally will not suffer a serious permanent shrinkage.

Like much that you read from that time, it was clear more water was needed for agricultural development in the arid West. The notion of a great city, of suburban lawns spreading to the horizon? Not so much. But however they were planning on using the water, it was clear from Mendenhall’s time that there was a problem.