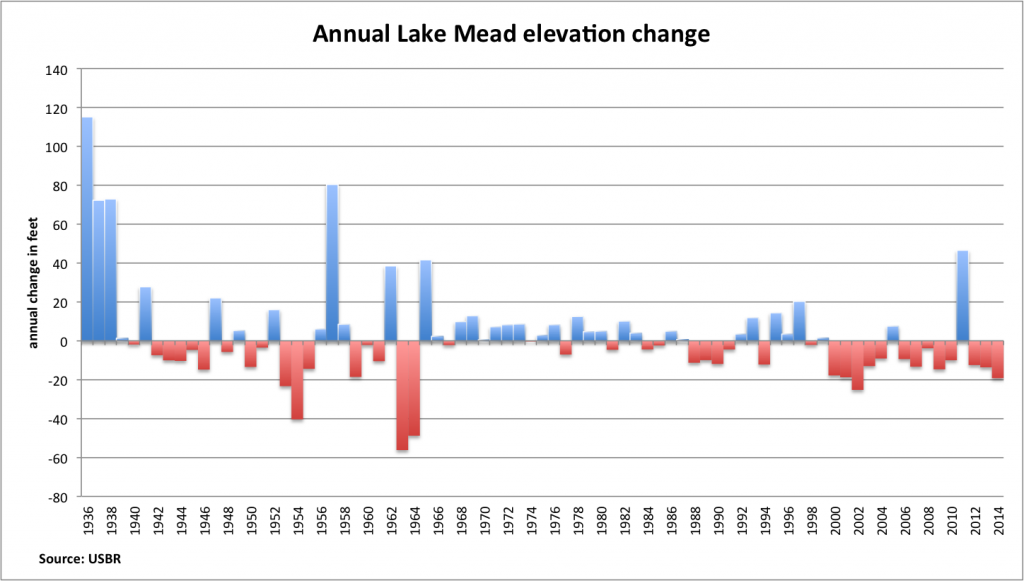

With just a few days left, it looks like Lake Mead will end 2014 down 19 feet, which would be the second biggest one-year drop of the “modern era” (the years since completion of Glen Canyon Dam upstream damped down the river’s ups and downs).

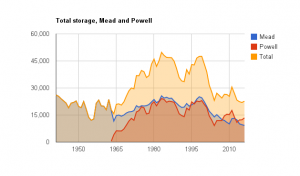

With inflow largely regulated by Glen Canyon Dam and outflow largely determined by downstream use, Mead is plumbing. Climate plays a role here, but climate is heavily buffered by management decisions, so to understand what’s happening we need to look at institutions as much as the weather upstream.

Here are the key factors responsible for this year’s big drop:

- Less inflow than usual – a release of only 7.48 million acre feet from Lake Powell, rather than the usual 8.23 maf, in conformance with rules aimed at keeping levels in the two reservoirs balanced (background here)

- More outflow than usual – the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has been cashing out some of the credits it had built up under the water banking scheme known as “Intentionally Created Surplus”, so water left in Mead in previous years as a hedge against drought is being used. Also, Mexico took out some of its banked water for last spring’s Minute 319 environmental pulse flow.

The previous pre-Glen Canyon Dam record for biggest one-year drop came in 2002, the last year in which California was allowed to use excess supplies before it had to curtail its usage to stay within its legal 4.4 million acre feet per year allocation.

All this is very orderly, and was expected, but that makes it no less unsettling if you’re Las Vegas or Arizona, looking at threats to long term water supply as Mead continues to drop.