update Feb. 4:

The official numbers are out, largely unchanged from the preliminary numbers:

Otowi

- max: 107 percent

- mid: 63 percent

- min: 33 percent

San Marcial

- max: 108 percent

- mid: 49 percent

- min: sorta zero (the models have a hard time with the bottom end of the range at San Marcial)

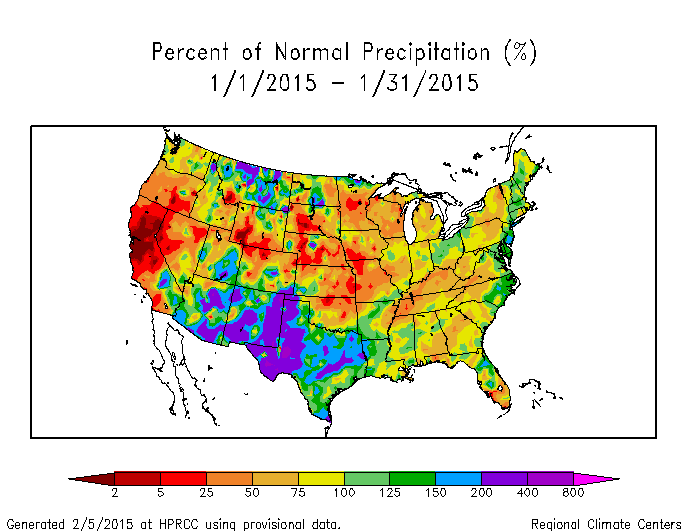

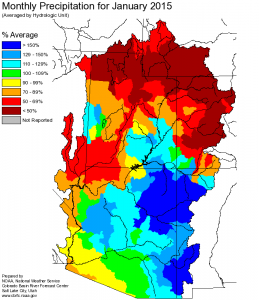

previously: The NRCS preliminary Feb. 1 forecast numbers are out, and despite last week’s storm, they continue to point to the fourth consecutive low flow year on the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

At Otowi, the key spot for measuring flow into the river’s mid-New Mexico valleys, the mid point of the forecast range is 450,000 acre feet of runoff from March through July, which would be 63 percent of the 1981-2010 average. The forecast offers max, mid and low numbers, which correspond to a one in ten chance on the wet side, the mid point, and a one in ten on the dry side. Here are the percentages:

- max: 101 percent

- mid: 63 percent

- min: 33 percent

What that’s telling us is that the snowpack is low now, and it would take great snow from here on out just to get us up to normal. And that if things stay dry, it could get a whole lot worse.

San Marcial, the last measurement point above Elephant Butte reservoir, looks crummier at the midpoint, but with a bigger spread:

- max: 109 percent

- mid: 50 percent

- min: sorta zero (the models have a hard time with the bottom end of the range at San Marcial)

These are preliminary numbers. NRCS will firm them up later in the week, and I’ll provide an update.

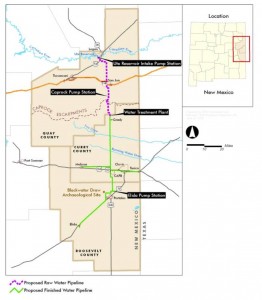

Who does this matter to? Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District farmers have essentially no water in storage, and will have a hard time storing any for the peak of summer at those midpoints. Lower Rio Grande farmers are in a similar situation. And the coalition of agencies trying to keep the river wet for the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow will have some scrambling to do.

On the plus side, despite last week’s storm, the roof above my new UNM office didn’t leak, so there’s that.