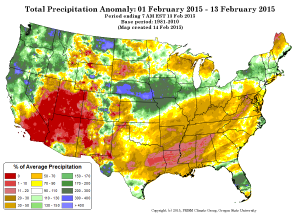

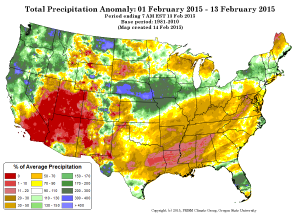

Precip anomaly, Courtesy PRISM

January was bad for snowpack and therefore spring runoff in the Colorado and Rio Grande basins. February has been worse. But we don’t use water at the basin scale, we use it one irrigation district and city at the time. Here I will attempt to sum up the current snowpack and water supply situation and share some thoughts about who is at risk, and who isn’t.

tl;dr: The Lower Basin – Arizona, Nevada and California – should be nervous about future risk, but this year they’ll be fine. For the Upper Basin, especially western Colorado ag, this is bad news now.

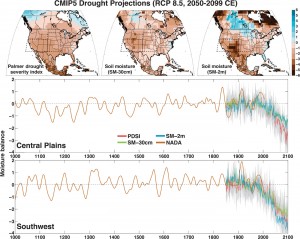

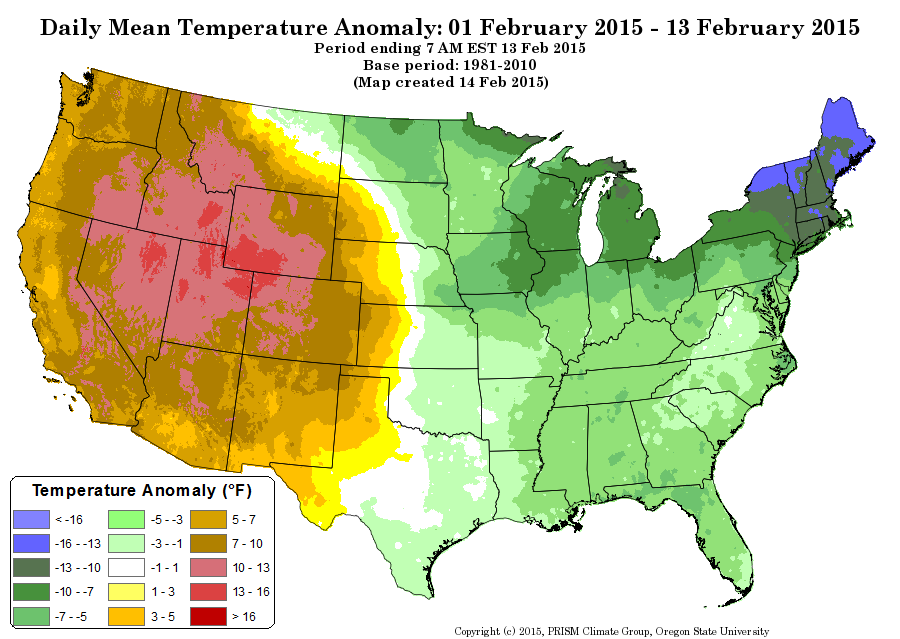

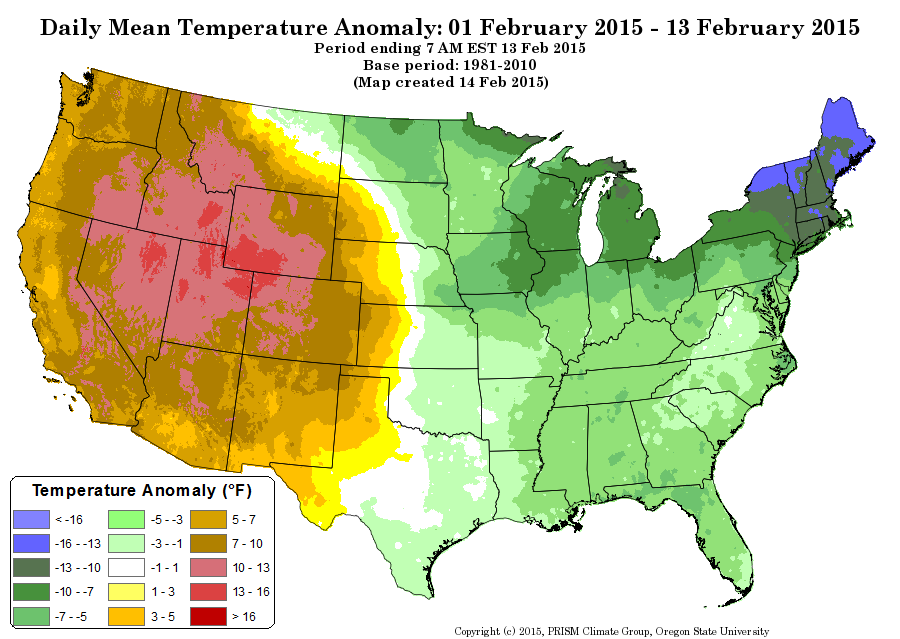

Across the interior West, February has been dry, but it’s the temperature anomalies that are killing us. Durango, which is a nice bell weather bellwether near the San Juan headwaters, and just over the divide from the Rio Grande headwaters, has had just one overnight low that was colder than average since the first week of January. Overall temperature anomalies for the first half of February across all of the Colorado River and Rio Grande high country have been at least 7F above average, in many cases more than 10F above average. This has been an epic warm spell.

temp anomaly, Courtesy PRISM

The result is a steady decline in the runoff forecast. The various basin forecasters run automated regression models, based on current snowpack, which provide a good snapshot of the change situation. They are all trending down. On the Rio Grande, projected flows at Otowi (the key measurement point in central New Mexico) have dropped from 49 percent of the 1981-2010 mean to 44 percent. On the Colorado River, unregulated flows (total available water) has dropped some 270,000 acre feet. That’s more than the entire annual consumptive use of the Las Vegas metro area, “lost” in just two weeks.

So who is at risk from all this?

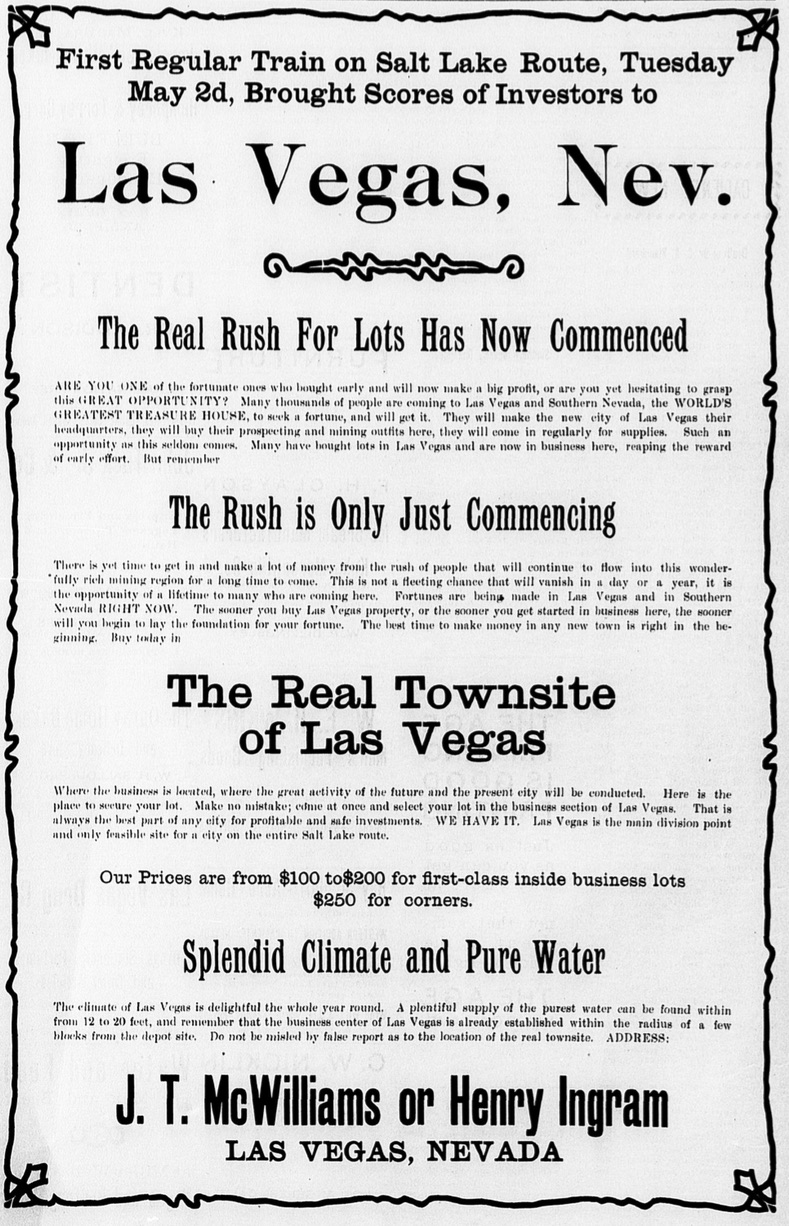

Let’s start with Las Vegas and the other water users of the Lower Colorado River Basin. In addition to Vegas, this includes Phoenix, Tucson, and Los Angeles/San Diego. More importantly (in terms of the volume of water used), it includes the Imperial Irrigation District and a lot of other farmers in the LoCo desert basins. For them, at least for this year, the dwindling snowpack means nothing. With two big upstream reservoirs as buffers, the water allocation rules call for full deliveries this year for all the Lower Basin water users. In the longer term, however, a shortfall upstream moves us closer to the point where Lake Mead drops so low that we could see a shortage declaration in the next few years. At that point, supplies available to Arizona and Nevada are reduced first. (What happens at that point is crazy complicated, see Brett Walton for the best explanation of the details.)

The Upper Basin is different. I had an interesting conversation recently with someone working in water in the state of Colorado who noted that the view of shortage is very different up there. While Lower Basin folks are all in a lather about the possibility of shortages at some point in the future, in the Upper Basin, where you’re getting your water directly from the mountain snowpack, shortage is imposed by nature and happens all the time.

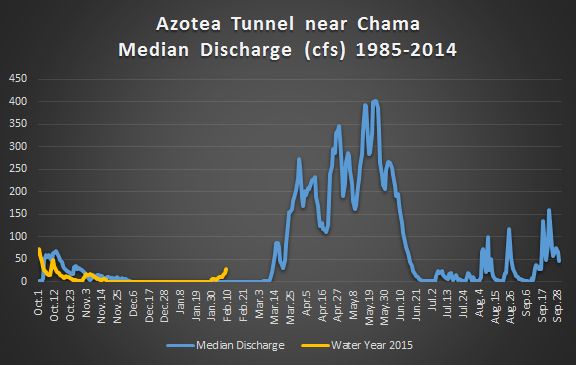

There, you have smaller irrigation districts near the headwaters, farmers pulling directly from depleted streams. You can see what happened to them during comparable bad times during the drought of the early ’00s. In wet years over the last decade, farmers in the state of Colorado used 1.5 million to 1.6 million acre feet. In drought years, they used 1.2maf or less. This is not operating rules imposing shortages because there is not enough water in a reservoir. This is hydrology – if there isn’t water flowing down the river, the field goes dry.

So if you’re in Phoenix and worrying about this, it’s OK to worry, but also be thankful that you’re not trying to make a living farming on Colorado’s west slope.