update, Thursday, 3/5: Final March 1 forecast numbers are in, unchanged for those in the preliminary quoted below.

previously: It says something about the drought on New Mexico’s Rio Grande in recent years that a forecast of 67 percent of average runoff into Elephant Butte Reservoir is good news.

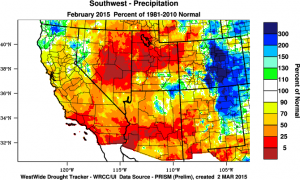

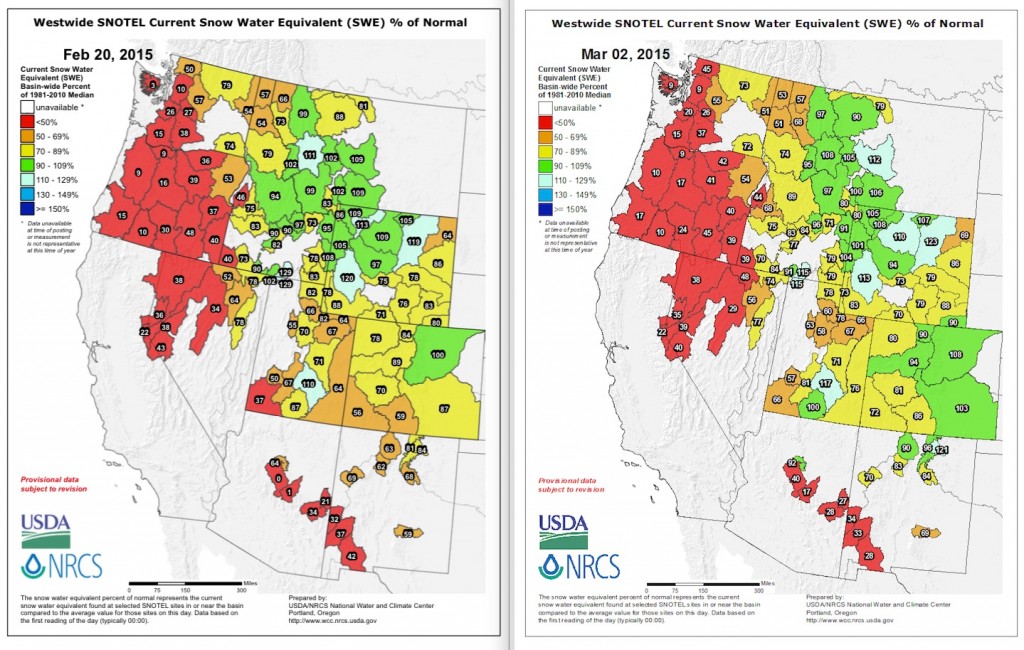

That’s the mid-point of the preliminary forecast sent around to New Mexico water managers and stakeholders today by the Natural Resources Conservation Service. The forecast includes the early March storm, which has pushed snowpack to 87 percent of average in the Rio Grande headwaters of Colorado and near normal in the mountain watersheds of northern New Mexico that feed the river. But as you head south, the numbers drop, and the forecast reflects that.

There’s still a big spread of uncertainty in the forecast, with a lot riding on what happens in March:

- wet (the 3 in 10 high-flow probability): 92 percent or above

- mid: 67 percent

- dry (3 in 10 low flow probability): 41 percent or below

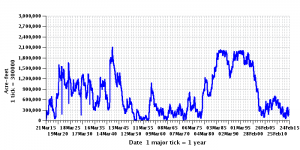

This is the fifth consecutive March 1 for which the forecast has been below-average bad news at San Marcial, the gauge at the head of Elephant Butte Reservoir, a point I’m calling out here because the greatest drought impact has been on farmers who depend on water from Elephant Butte. After flush years in the ’80s and ’90s, irrigators drained the Butte in the first decade of the 21st century. As I wrote a couple of wrote a couple of years ago in the newspaper:

Yields are already down – 30 percent in the case of onions, one of the valley’s money crops. A drive through the valley shows tiny spring onion plants already stunted by the salt accumulating in the soil beneath them.

As for chile, Shayne Franzoy said the Hatch Valley should have a decent crop this year for the packers, like Bueno Foods in Albuquerque, that depend on their chile. But if drought conditions continue, the future is less certain. “If we don’t have surface water in the Hatch Valley,” Jerry Franzoy said, “it’s gonna die pretty quick.”

That was two years ago. It hasn’t gotten better.