Article VII of the Rio Grande Compact is one of the keys to allocating the river’s supply among Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas:

Neither Colorado nor New Mexico shall increase the amount of water in storage in reservoirs constructed after 1929 whenever there is less than 400,000 acre feet of usable water in project storage….

Operationally, this is critical. It means that in drought conditions, irrigators cannot store spring runoff in essentially all upstream reservoirs for summer use. There’s been some flexibility written into the law in practice, but it only operates at the margin. It basically means that during droughts, one of the water managers’ most important tools (storage) is constrained.

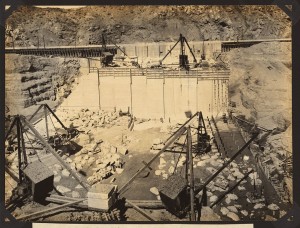

Elephant Butte Dam site: foundation of dam in bed of river, third section in foreground under construction, looking west, 1914 Feb. 27, courtesy Library of Congress

If my records are correct (and don’t hold me to the date, this is me looking up stuff in my files on a Sunday morning without benefit of actually confirming with people who know, i.e. “doing journalism”), we’ve been in Article VII since July 8, 2010. But with the big last-of-Februrary-first-of-March storm, there are signs usable project storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir could rise above the magic 400,000 acre feet some time around the first of May. That would allow the Middle Rio Grande Irrigation District to sock away a bit of extra water for late summer alfalfa cuttings.

The variables here illustrate the way a big reservoir integrates across both supply and demand functions. As soon as the Elephant Butte Irrigation District downstream begins taking its water out of Elephant Butte, it’ll likely drop back below 400k and we’ll be back in Article VII. The current “official” date for the start of irrigation is June 1, but it looks like it may be earlier – like the middle of May. Depending on runoff between now and then, EBID’s start might even slip earlier, which would trigger the usual “black helicopters” north-south water war trope about how EBID and the federal government are in cahoots to keep Article VII storage restrictions in place.

I am generally skeptical of black helicopters.